The Adams—Cuomo Coalition

Eric Adams is running for re-election as an Independent, paving the way for Andrew Cuomo to inherit the Mayor's working-class base

In late March, rivals of former Governor Andrew Cuomo, the early frontrunner to become New York City’s next Mayor, received a DEFCON 2 warning three months before primary day.

Three consecutive polls (Honan, Data for Progress, Emerson), all released within thirty-six hours of one another, revealed three consistent themes about the immediate trajectory of the race:

Andrew Cuomo has a large lead (approximately 40%)

Zohran Mamdani, the democratic socialist lawmaker from Queens, is the only non-Cuomo candidate registering in the double-digits (mid-teens).

A crowded third-tier of candidates are mired in the single-digits: Brad Lander, Adrienne Adams, Scott Stringer, Zellnor Myrie, and Jessica Ramos.

A review of the cross-tabs proved bleak. Despite Mamdani (+14) besting Cuomo with voters under-45, while playing him close among the college-educated (-4) and those who live in Brooklyn (-7), the former Governor won all remaining demographic groups “comfortably.” The frontrunner’s most pronounced advantages over his rivals came amongst: Blacks (+41), Bronx residents (+36), voters over-45 (+38), and those without a college-degree (+38).

With each new poll, the heat on Cuomo’s rivals increased precipitously. Press Releases, to regain the narrative and grasp some semblance of oxygen in this attention economy, were issued en masse. The Working Families Party countered with an ambitious slate of four, while promising to coalesce behind the most viable come late May. Indeed, a collective gulp could be heard across the spectrum of the anti-Cuomo political class. Within days, the next wave of elected officials anxious about being on the losing side endorsed the former Governor, including Rep. Gregory Meeks, chair of the infamous “Queens Machine,” and once-upon-a-time, the political patron of Adrienne Adams. Mayor Eric Adams, whose corruption case was dropped soon thereafter, chose to bypass certain defeat in the fast-approaching Primary, opting to instead run in November as an Independent, as polls showed Cuomo had already subsumed his working-class Democratic base.

Many dismissed the prohibitive polls off-hand due to Cuomo’s unrivaled name recognition; certainly a factor, particularly amongst non-college educated voters — but only to an extent. Others harkened back to the cautionary tales of Andrew Yang and Christine Quinn, frontrunners who imploded by the campaign’s conclusion.

However, both of these counters, in my estimation, fall short in addressing the electoral strength of Andrew Cuomo. And, while Mayor Cuomo is not inevitable, his standing — with less than three months until Primary Day – is significantly stronger than past early frontrunners.

For one, at a comparable juncture in the political calendar, the likes of Quinn and Yang were already hemorrhaging support. And, even at their apex, each consistently registered in the upper-twenties; Yang only broke thirty-percent once, while Quinn stopped polling north of thirty-percent more than five months before the Primary.

Neither were ever close to the 40% threshold.

Most importantly, the contours of Andrew Cuomo’s coalition are more conducive to retaining support as attacks escalate in the coming months. Whereas the early polling strength of Christine Quinn and Andrew Yang was tied to the whims of civically-engaged, white collar voters, Cuomo’s strength is anchored in the working and middle-class Black and Latino neighborhoods of the outer boroughs – communities that have routinely formed a bloc of his most loyal support, particularly during the final months of his tenure as Governor and his subsequent years in the political wilderness. Following months of relentless strikes from opponents (and a healthy dose of negative press), both Quinn and Yang imploded in Manhattan, and possessed little support in the outer boroughs to retreat to — ultimately dooming their chances. In contrast, Andrew Cuomo’s strong early numbers are reminiscent of the durable coalition, akin to a political firewall, that elevated Eric Adams to City Hall four years ago.

Now, with the Mayor no longer participating in the Democratic Primary, Andrew Cuomo is poised to not only inherit the coalition that elected Eric Adams — but, potentially, make it stronger.

The last time Andrew Cuomo’s name appeared on a Democratic Primary ballot was September of 2018, while Eric Adams won his Party’s nomination in June of 2021. Given the passage of time, some might be compelled to discount these findings. I’d caution that, for all of the thermostatic public opinion, particularly among Democrats during the era of Donald Trump, the political whims of New York City’s older, outer borough working-class — the coalition bedrock of both Eric Adams and Andrew Cuomo — have not drastically changed, especially with respect to candidates whom they have known for decades. However, the fundamentals of each race, as well as the strength of their respective opponents, were not created equal.

Andrew Cuomo, armed with a twenty-five million dollar warchest and the endorsement of New York’s largest labor unions, outspent actress Cynthia Nixon tenfold. While Nixon had clout across Brownstone Brooklyn and Manhattan’s affluent enclaves, dragging down the Governor’s numbers throughout the urban core, she lacked validators in working-and-middle class neighborhoods of all races, dooming her to one-third of the citywide vote. Whereas Kathryn Garcia, endorsed by The New York Times Editorial Board (in 2018, so was Cuomo), submitted a thoroughly dominant performance in Manhattan (she won over seventy-percent), the former Sanitation Commissioner also convincingly won middle-class Jewish areas (Forest Hills, Riverdale) and single-family home, white ethnic communities (despite her pre-Abundance support for upzoning their neighborhoods). Nonetheless outspent by Eric Adams, the margin was not prohibitive (owed to stricter campaign finance limits), as Garcia rapidly ascended the polls via earned media over the final six weeks, while taking almost zero incoming hits from the field, ultimately coming within one-percent (seven thousand votes) of becoming Mayor.

Thus, to properly adjust for these vastly different fundamentals, I calculated Cuomo’s performance by both Assembly and Election District compared to his citywide average (66.6%). In my opinion, this metric (+/-), rather than the simpler 1:1 vote share comparison between Cuomo and Adams, is a more accurate reflection of the former’s present-day coalition, both in terms of breadth and depth, given the ex-Governor’s recent scandals and diminished institutional advantages.

Andrew Cuomo’s Core Support Mirrors Eric Adams

[Spider-Man Meme]

They’re the same picture! Well… almost — but we’ll get to that later.

Let’s start with what they have most in common:

Older Black voters — spanning class (renters, cooperators, homeowners) and national origin (African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans) — are the bedrock of the Democratic Party in New York City. Four years ago, they formed the foundation of the Eric Adams coalition, along with with Orthodox and Hasidic Jews (frequent ticket-splitters at the federal level), a time-tested winning coalition that not only nominated Adams, but helped elevate his predecessor, Bill de Blasio.

“The winning coalition of Eric Adams saw middle-class African-American and Afro-Caribbean homeowners in Southeast Queens and the Northeast Bronx (7-to-1), along with working class and low-income Black renters in East New York, Brownsville, and East Flatbush (9-to-1) supported the former police officer by prohibitive margins. Adams handily won middle-income developments like Co-Op City (5-to-1), Parkchester (4-to-1), Rochdale Village (13-to-1), and Starrett City (10-1).” (The Narrative Wars)

Supermajority Black neighborhoods were among the few districts where Eric Adams (2021) received a higher vote share than Andrew Cuomo (2018). And, when comparing their respective over-performances (+/-) Adams clears Cuomo by a healthy margin. Although Andrew Cuomo’s strength in Black communities is evident, said support does not appear to be insulated to the degree it was for Eric Leroy Adams. This “robust support amongst working-class Black New Yorkers helped [Adams] win many gentrifying neighborhoods — like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Flatbush — by healthy margins.” Here, his vote share was also higher than Cuomo, leading me to believe that Adams not only captured a higher percentage of the Black vote, but mobilized his core constituency to the polls more effectively.

“Amongst Borough Park’s Hasidim (10-to-1), the Orthodox of Midwood (6-to-1) and Far Rockaway (8-to-1), South Williamsburg’s Satmar (20-to-1), and the Chabad Lubavitch of Crown Heights (18-to-1) — Eric Adams won, overwhelmingly.”

Four years ago, even Eric Adams, the Brooklyn Borough President with decades-long relationships to influential rabbis and local power brokers, was not the first choice of Kings County’s various Hasidim and Orthodox Jewish sects. And, while the lionshare of said support, initially, belonged to Andrew Yang, the overwhelming majority came home to Eric Adams upon the former’s elimination, an ultimate advantage of close to ten-thousand votes, far greater than Adams’ seven-thousand vote margin-of-victory. And, while there are lingering resentments in Orthodox and Hasidic communities with respect to the former Governor’s pandemic-era restrictions on large gatherings, Cuomo is relentlessly courting the most Pro-Israel elements of the electorate, charging that his opponents, two of whom are Jewish (Cuomo is Catholic), are insufficiently concerned with the plight of Jewish voters, while equating anti-zionism with anti-semitism (some Hasidic sects, like the Satmar in Williamsburg, are religiously anti-zionist). However, rabbinical power brokers, given the government’s oversight with respect to their community norms, such as the Yeshiva school system, covet being on the proverbial winning team. And, in communities where relationships are, quite literally, the key to unlocking several thousand votes, Andrew Cuomo has the connections to ensure that, come Primary Day, Hasidic and Orthodox communities in Borough Park, Midwood, South Williamsburg, Far Rockaway and Kew Gardens Hills will rally behind him, as they have done for decades.

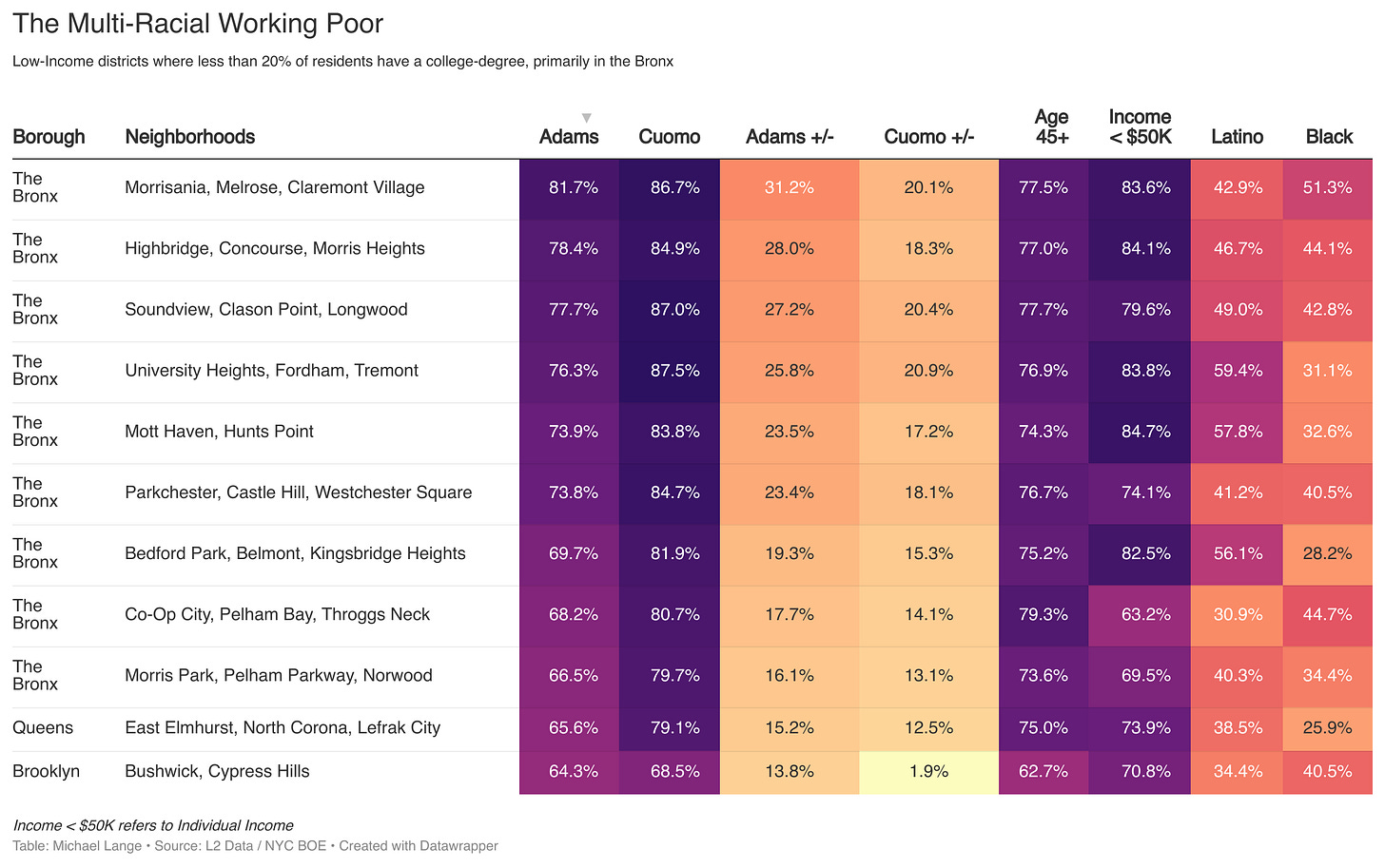

Eric Adams electorally united his base of Black voters with robust margins amongst Latinos, from the heavily-Dominican neighborhoods adjacent to Crotona Park (4-to-1) as well as the historically-Puerto Rican enclaves of Soundview, Hunts Point, and Mott Haven (3-to-1). Across the Bronx’s many low-income neighborhoods, where people-of-color are more than ninety-percent of the electorate, Adams easily outpaced his opponents. Among those who did vote (unsurprisingly, civic participation is lowest among the least fortunate), many of whom rely upon rent-stabilization and housing vouchers to maintain their footing in this unforgiving city, the public safety message of the Brooklyn Borough President resonated to a resounding degree. Indeed, support for the former police captain amongst the city’s working poor was resolute. Case and point, every NYCHA development in New York City voted for Eric Adams.

Andrew Cuomo’s prohibitive (early) lead in New York’s lowest-income county (+36), according to Data for Progress, goes hand-in-hand with his strong standing amongst Latino voters (+23), and those without a college degree (+38); two intertwined dynamics which, partially, reflect his overwhelming name recognition. When evaluating the past performances of Andrew Cuomo and Eric Adams, their standing amongst Hispanic communities, particularly in the Bronx, is comparable; Cuomo routinely performed ten-points better, but Adams’ +/- was marginally higher despite facing an opponent with a traditionally-Hispanic last name. Nonetheless, with Cuomo echoing a similar message centering public safety and combating disorder, the well-known former Governor remains in pole position to once again carry the neighborhoods with both the highest crime, and lowest incomes.

Cuomo’s Support is Broader, but Softer

However, upon a closer inspection of the aforementioned comparison map, one can glean several neighborhoods where Andrew Cuomo’s support — borne out from previous campaigns, reinforced by early polling, and theoretically applicable to the upcoming Primary — stretches beyond the potent, but nonetheless contained coalition of Eric Adams.

The common theme? All are politically-moderate, relatively affluent districts with a considerable share of homeowners. In fact, Cuomo consistently outperforms Adams with White voters of all socio-economic classes. Unsurprising, but nonetheless noteworthy.

For instance, throughout Manhattan’s affluent enclaves, where voter turnout is the highest in New York City, Eric Adams barely exceeded twenty-percent in the final round of ranked-choice-voting against New York Times-endorsed Kathryn Garcia. Along the Upper East Side’s wealthiest corridor, a stretch of doorman buildings and multi-million dollar townhouses adjacent to Central Park from 59th Street to Carnegie Hill, Adams dominated the fundraising circuit, but nonetheless lost three-quarters of the vote to Garcia. Furthermore, Adams struggled in middle-class, historically-Jewish neighborhoods — losing Forest Hills in Queens (3-to-1) and the Riverdale section of the Bronx (5-to-2). Even among moderate-to-conservative Democrats (think Irish and Italians from the outer boroughs) — Staten Island’s Southern Shore, Maspeth & Middle Village, and the western half of the Rockaway Peninsula — the technocratic Garcia outpaced the law-and-order Adams. And, while Cuomo cannot match Garcia’s margins in Manhattan, he can avoid the carnage that nearly kept Adams from Gracie Mansion.

Here, in neighborhoods where Michael Bloomberg once excelled, Andrew Cuomo is well-positioned to expand his coalition beyond that of Eric Adams.

The dwindling population of ethnic whites, particularly Italians in Whitestone, Howard Beach, and Country Club will largely cast their ballots for Mario’s son. Many moderate Jews will see the former Governor as reliably Pro-Israel, and a bulwark against the Palestinian-sympathetic left. Now a resident of tony Sutton Place, Andrew Cuomo will be able to win over wealthy, white Manhattanites in a way Eric Adams, the Black police captain from South Jamaica, never could. In 2021, Eric Adams won Staten Island by five-hundred votes against Kathryn Garcia; in 2018, Andrew Cuomo did not lose a single precinct in Richmond County to Cynthia Nixon.

While the electorate of older, moderate white voters can no longer form the base of a winning coalition in the Democratic Primary, such a contingent remains an important complementary piece on the pathway to fifty-percent plus one. This June, that is all Andrew Cuomo needs.

While the Adams–Cuomo voter may be the story of the 2025 Democratic Primary, the Garcia–Cuomo voter remains the determinate variable as to whether or not the former Governor will reach City Hall.

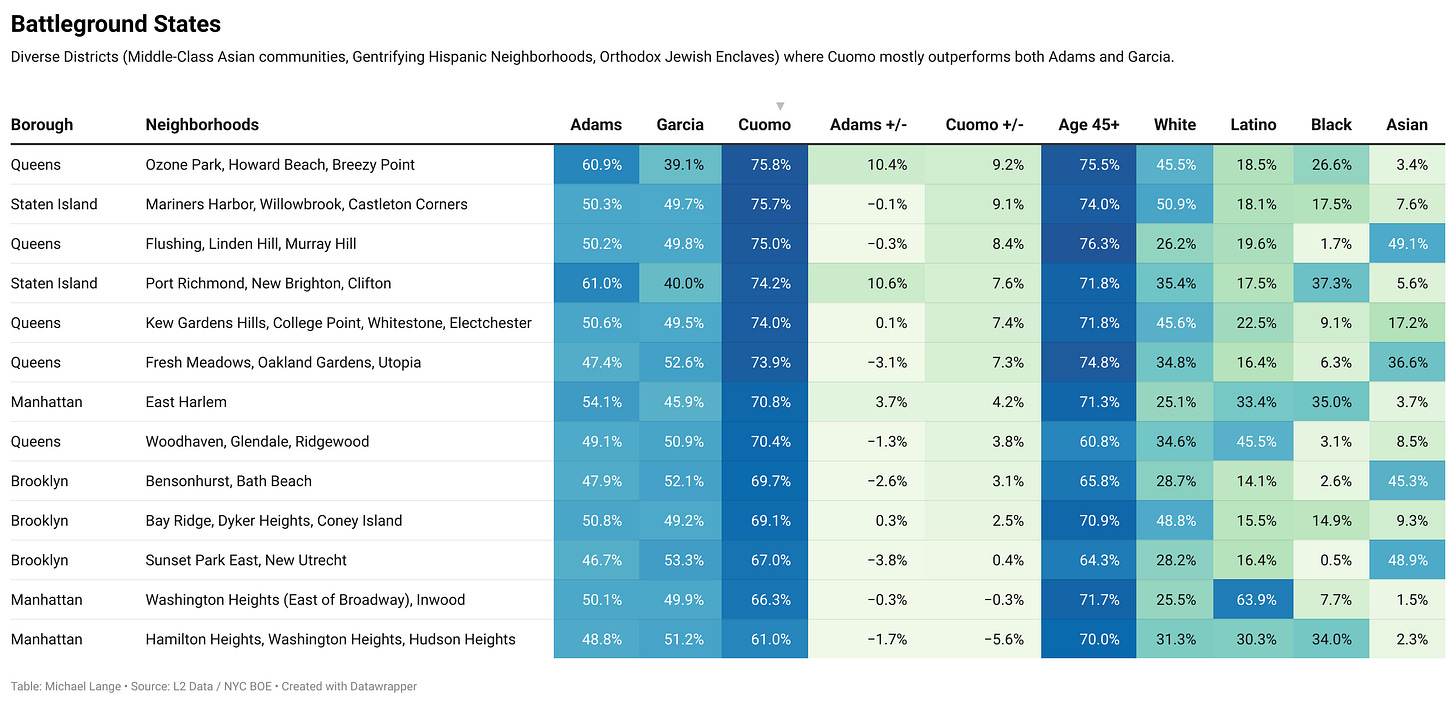

While the previous Mayoral race, at least in the ultimate round of ranked-choice-voting, was largely reduced to a voter turnout struggle between upper-class, white-collar professionals and the Black and Brown working-class of the outer boroughs, several neighborhoods (“Battleground States”) were decided by relatively-close margins, critical in a contest decided by seven-thousand votes. These diverse districts with close outcomes contain markedly different electorates: working (Sunset Park) and middle-class (Linden Hill) East Asians; gentrifying Hispanic neighborhoods in Manhattan (East Harlem, Washington Heights); relatively small, but electorally impactful Orthodox Jewish populations (Kew Gardens Hills, Fresh Meadows); older, white ethnic strongholds (Breezy Point, Glendale), some of which are gradually diversifying (Bay Ridge, Whitestone).

While both Eric Adams and Kathryn Garcia were crushed by Andrew Yang in East Asian neighborhoods — Flushing, Elmhurst — upon the latter’s elimination, the final duo (Garcia handsomely benefited from Yang’s cross-endorsement) played to a relative stalemate across the aforementioned Chinese enclaves. Now, one of the last active and influential local political machines, led by Bill Colton and Susan Zhuang, has endorsed Andrew Cuomo, giving him the inside-track to a strong showing in the residential, Chinese and Italian neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Bath Beach and Gravesend — and an eventually plurality with one of New York City’s fastest growing (and Republican-trending) demographics.

Crucially, almost every neighborhood listed below — split between Adams and Garcia four years ago — was convincingly won by Andrew Cuomo in 2018.

While Eric Adams’ electoral coalition was rooted in Black and Latino neighborhoods across the Outer Boroughs, he received considerable support, behind-the-scenes, from Manhattan’s business elite. Adams’ campaign coffers, not to mention aligned Independent Expenditures, were bankrolled by mega-donations from Real Estate developers and Republicans. This coalition, a union of the ruling and working-class, was enough for Adams to eke out a narrow, one-percent victory over Kathryn Garcia in the final ranked-choice-voting runoff. And, save for the full-throated support of The New York Post, such is a coalition Andrew Cuomo is poised to inherit as June 24th approaches.

For the past thirty-five years, the path to City Hall has run through Queens, the borough where the Cuomo dynasty began, now the most diverse county in the United States. Now, in spite of all the demographic change in the World’s Borough, Cuomo’s coalition appears tailor-made for the neighborhoods east of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. Already, both the Democrat and Republican nominees for the plurality-Asian Eleventh State Senate District — a stretch of Eastern Queens which snakes from Little Bangladesh along Hillside Avenue to the suburban peninsula known as Douglaston, eventually landing on the shores of working-class College Point — have pledged their support to Andrew Cuomo.

To prevail in this all important borough, Cuomo’s rivals will have to either crack his base in vote-rich Southeast Queens, or run up the score in the gentrified, westernmost neighborhoods and win the voter turnout battle through ballot exhaustion, cross-endorsements, and attrition.

Andrew Cuomo will be very difficult to dethrone in the Bronx, the borough where he once led outreach on behalf of his father in the sweltering summer of 1977. Namely, the former Governor will have the inside track to (once again) win many of the borough’s varied constituencies — Dominicans in University Heights, Blacks in Williamsbridge and Edenwald, moderate Jews in Riverdale and Fieldston, Puerto Ricans in Castle Hill and Soundview, Italians in Country Club and Morris Park — where older voters, intimately familiar with Cuomo’s legacy, exercise disproportionate influence over the electorate.

Will Brad Lander and Scott Stringer make Spuyten Duyvil competitive? Can Zohran Mamdani expand his influence from Parkchester and Westchester Square into the rent-stabilized tenements of the South Bronx? Does Jessica Ramos have a prayer with the Latino electorate outside Queens? Could Adrienne Adams make inroads with working-and-middle class Afro-Caribbean and African-American voters in Wakefield and Co-op City?

Staten Island? Fuhgeddaboudit. It would be hard to design a borough and constituency more tailor-made for Andrew Cuomo: working-class Black and Latino neighborhoods (Mariners Harbor, Port Richmond, Stapleton, Clifton) ribboning the Island’s North Shore, coupled with moderate, Italian-American homeowners along the Eastern and Southern Shore. Nonetheless, only twenty-five thousand votes came from the entirety of Richmond County in the previous Mayoral Primary, less than several Assembly Districts in Brownstone Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Undoubtedly Andrew Cuomo will struggle across the left-leaning, professional-class neighborhoods — Park Slope, Fort Greene, Williamsburg, Long Island City, East Village — who soured on the Governor long before he stepped down. However, in New York City, that alone cannot make a winning coalition. Of the many stories told on June 24th, the Generational Gap will be at the forefront, nowhere more so than across the many corners of Brooklyn, where the electorate is skewed significantly by age. In neighborhoods like Greenpoint and Bushwick, sixty-percent of the electorate is under-45 years old, while in predominantly Black communities like Canarsie and East New York, eighty-percent of Democratic voters are over-45. Zohran Mamdani, already, remains the unquestioned favorite of the former, and will continue to consolidate the burgeoning youthful, college-educated electorate in the coming months. With an impressive small-dollar donor base, vast volunteer operation, and early polling strength primarily emanating from Kings County, how many new Primary voters can Mamdani bring into an electorate that is traditionally dominated by “triple-prime” seniors?

Speaking of, the former Governor’s past performance almost perfectly corresponds to the age of the electorate. Andrew Cuomo’s ceiling in Brooklyn is capped, but his floor — owed to older Black voters, Orthodox and Hasidic Jews, immigrants from the former Soviet Union, and the small homeowner class — remains insulated, to an extent, from his fervent opposition.

Manhattan, where the former Governor remains vulnerable, remains the key to preventing Andrew Cuomo from reaching City Hall. Fickle white-collar liberals, most-responsive to damaging press and the whims of the media class, are not only one of the largest electorates in New York City, but are oftentimes the late deciders that shape Mayoral outcomes. Four years ago, they broke decisively for Kathryn Garcia, and nearly proved to be Eric Adams’ Achilles Heel. While Cuomo was already losing ground with this constituency prior to the avalanche of scandals that expelled him from Albany, his opponents have struggled to consolidate support among the affluent urban core. Here, in the recent Data for Progress poll, both Scott Stringer (9%), the former Manhattan Borough President and City Comptroller, and Brad Lander (8%), the sitting Comptroller who won Manhattan by thirteen points in 2021, were polling in the single-digits, while the former Governor gobbles up one-third of the vote. To put it simply, that won’t cut it. Absent pronounced gains across the outer boroughs, Cuomo will have to bottom-out in Manhattan, fast, for his rivals to have any chance on Primary Day. The good news for Cuomo’s opponents? Wealthy Manhattanites will be the most reactive to a relentless negative advertising campaign that targets the former Governor.

Thus far, most rival candidates have only shown the capacity to reach segments of the electorate. Many, with less than three months until Primary Day, are still trying to develop a discernible base of voters to begin with.

The sole non-Cuomo candidate with a well-defined base, Zohran Mamdani, appears on course to eclipse twenty-percent of the vote in the first round of ranked-choice-voting, behind a coalition of college-educated progressives, South Asians, and Muslims. And, comparable to the core of the Adams/Cuomo coalition, as right-leaning attacks on Mamdani escalate in the coming months, the democratic socialist’s base will remain stable, owed to his longstanding relationship with each respective constituency. The question, as is the case for Cuomo, is whether Zohran’s ceiling will be diminished by negatives, or simply the racial and class politics that traditionally dominate New York City.

Among all of the Cuomo challengers, Brad Lander is the only candidate who has won a citywide Democratic Primary in the past decade, defeating Corey Johnson by four points in a come-from-behind victory for Comptroller. So far, Lander’s five-borough sequel has been fine. He’s on pace to max out on matching funds come the next deadline, has successfully peeled off Upper West Side clubs from rival Scott Stringer, and counts the vote-rich, Brownstone neighborhoods west of Prospect Park as his electoral base. Nonetheless, when Lander first entered the race, he expected a (mostly) one-on-one faceoff with Eric Adams, with the full weight of the left-liberal establishment uniformly lined up behind him. Instead, the Mayor was indicted, nearly removed, and is now running as an Independent. Andrew Cuomo lurked for months, only to reemerge with a commanding lead, proving far more difficult an opponent than the diminished incumbent would have been. Nor was Lander alone on the left, as Zohran Mamdani barnstormed his sleepy opponents, rapidly amassing headlines, volunteers, money, and most importantly, oxygen. In short, the landscape shifted, drastically, under Brad Lander’s feet. April will be an critical month for the Comptroller.

Council Speaker Adrienne Adams has only been in the race for a matter of weeks, after prodding from labor leaders and State Attorney General Letitia “Tish” James. As such, she did not qualify for the upcoming April 15th matching funds disbursement (Cuomo did), leaving her campaign without the coveted, multi-million dollar infusion of funds until (at least) May 30th, a difficult situation for a candidate sorely lacking name recognition. Her launch, in Rochdale Village, was a spirited affair, as the Speaker, flanked by both her Council colleagues and the Divine Nine sorority, delivered a riveting address where Adrienne Adams appeared every bit the candidate who could diminish Cuomo’s standing with Black voters, particularly women. However, lacking the millions of dollars necessary to hit the airwaves until the final four weeks, her primary challenge will be to counter Cuomo’s “inevitability” that has already pushed several Black lawmakers, including a controversial cadre from her native Southeast Queens, into the former Governor’s corner.

Scott Stringer has high favorables and solid name recognition (seventy-percent), but has consistently seen his polling slide. For months, both Zellnor Myrie (qualified for matching funds) and Jessica Ramos (not qualified for matching funds) have failed to establish a base within the electorate, boxed out on the left by Zohran Mamdani (and, to a lesser extent, Brad Lander) and with working-class voters by the institution of Andrew Cuomo (and, to a lesser extent, the skeleton of Eric Adams). Historically, the frontrunner’s prohibitive early lead would scramble the anti-Cuomo factions, potentially leading to dropouts and consolidation in the coming weeks. Yet, the introduction of ranked-choice voting (akin to an instant runoff) diminishes vote-splitting concerns in the Democratic Primary. Furthermore, struggling campaigns who have received millions in public matching funds, are disincentivized from dropping out, as liquidity, theoretically, presents the opportunity to reverse fortune; not to mention, few consultants would advise their boss to willingly cut short their respective five-figure paydays.

And, with petitioning officially concluded — neither Kathryn Garcia nor Letitia “Tish” James will be walking through that door. The current crop, for better or worse, will be the field of Andrew Cuomo challengers on Primary Day.

The solution to the anti-Cuomo cluster has been a wholehearted embrace of ranked-choice-voting strategy. In a moment where the Democratic Party’s approval rating is less than thirty-percent, there is tremendous opportunity for The Working Families Party, who unveiled a slate of Mamdani, Lander, (Adrienne) Adams, and Myrie last week. According to The New York Times, “In May, the group plans to throw its support behind a single candidate that its leaders believe is best positioned to defeat Mr. Cuomo… Party leaders have not yet decided on a concrete strategy for how to consolidate support around their first choice, but they have weighed obligating other candidates seeking the group’s endorsement to cross-endorse the party’s top choice.” The WFP slate, coupled with the D-R-E-A-M strategy — Don’t Rank Eric (or) Andrew (for) Mayor — have emerged as the broad, anti-Cuomo orientation of the political class.

Nonetheless, the viability of both strategies hinge on a critical mass of voters adopting said ranked-choice-voting preferences. Not only will this require millions of dollars in fundraising to execute correctly, multiple candidates, not just Zohran Mamdani, will have to organically improve their standing (preferably at Cuomo’s expense), amongst the Democratic electorate in the next ten weeks. After all, a tag-team effort requires a team.

Yet, absent consolidation, so long as Andrew Cuomo is absorbing forty-percent of the vote, this will prove extremely difficult. For any anti-Cuomo Independent Expenditure, steps one, two, and three must be dragging down the frontrunner’s numbers at all costs. “Having a slate strategy doesn’t do anything if you can’t kill Cuomo,” Ross Barkan told me.

But that’s not the only issue. Attention, at this critical juncture in the race, remains a finite and scarce resource. In this new political economy — which rewards the well-known, the polarizing, and the charismatic — the likes of Andrew Cuomo, Eric Adams, and Zohran Mamdani thrive, while the rest, thus far, have struggled. Nor should the candidates currently mired in the single-digits take solace in the notion that, soon enough, they will be able to air television advertisements in the nation’s most expensive media market. Andrew Cuomo is going for the kill right now, and many anxious lawmakers and labor unions are more concerned with returning to the (notoriously vengeful) former Governor’s good graces than reckoning with his considerable baggage. Already, a Super PAC friendly to Cuomo has reserved their first TV advertisements. This is a DEFCON 2 moment.

Furthermore, the liberal and progressive institutions once capable of countering a force like Andrew Cuomo are amidst their own inflection points. I do not use the word existential lightly, but such is the task ahead of the Working Families Party over the next seven months. Does WFP, absent the labor unions that Cuomo jettisoned from their coalition, have the juice to slay their old foe once and for all? Furthermore, it remains unclear to what extent The New York Times Editorial Board, the singularly most influential endorsement in New York City politics, will weigh in on the most consequential race of the calendar year; recent reporting from Semafor indicated that the Editorial Board is “reconsidering” their much-maligned decision to pull-back from local endorsements.

Increasingly, in this moment of profound uncertainty for the liberal-left, many are turning to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, currently at the peak of her powers as buzz builds around a future campaign for US Senate (or President). Headlining the nationwide “Fight Oligarchy” tour, AOC possesses unrivaled and unique reach into the Democratic electorate, particularly amongst the urban working-class. Four years ago, Ocasio-Cortez endorsed Maya Wiley in early June, and helped power her to second-place in the initial round of ranked-choice-voting (she was overtaken by Garcia in the penultimate round). Now, in order to stop Andrew Cuomo, AOC will not only have to intervene sooner, but with greater force than ever before. The Bronx and Queens, home to the mosaic known as New York’s 14th Congressional District, are Andrew Cuomo’s strongest boroughs, after all.

Bi-lingual television advertisements. Rallies (plural), ideally with Bernie Sanders. Instagram lives (plural). Calls to persuadable, but not ideologically-aligned colleagues (Hakeem Jeffries, Adriano Espaillat). Political capital, carefully harnessed over the years, will have to be spent in spades to stop Andrew Cuomo. With great power comes great responsibility.

Four years ago, Eric Adams lurked in second-place for the vast majority of the campaign, only emerging with a slim polling lead over the course of the final five weeks. The trajectory of Adams’ campaign, peaking at the perfect time, yet barely surpassing fifty-percent in the ultimate round of ranked-choice-voting, was reflective of concentrated strength, but a limited coalition; underlying dynamics which, for months, kept the mercurial dark-horse out of his opponent’s crosshairs — until it was too late. Had Eric Adams been subjected to a coordinated, months-long onslaught from rivals, similar to what Andrew Yang endured, the Brooklyn Borough President’s coalition would have atrophied further, and Maya Wiley or Kathryn Garcia would have become Mayor instead.

While Andrew Cuomo, the clear frontrunner months in advance, will not benefit from the same stealthy rise to the top, the former Governor now has the inside-track to the coalition (Blacks, Latinos, Orthodox/Hasidim) that Adams rode to victory four years ago; not to mention credible, time-tested paths to win over segments of the electorate (Ethnic whites, wealthy Manhattanites, working-class East Asians, and middle-class Jews), that were never firmly in the Mayor’s corner. However, said strength, rooted in both objectivity and projection, will be the catalyst for a no holds barred, all-out assault on Andrew Cuomo’s favorables over the next three months.

But, will the attacks resonate?

While thermostatic public opinion defines the Trump era, the whims of rank-and-file Democrats across New York City’s outer boroughs are more consistent, and electorally durable, than their affluent, well-educated neighbors. For decades, the Cuomo coalition of older voters has remained the time-tested recipe for winning Democratic Primaries in New York City. And, while that dynamic is gradually changing, as the Democratic electorate becomes younger and more college-educated, one cannot become the Mayor of New York City without winning the hearts and minds of seniors. This is not Boston (no offense, Michelle Wu). Cuomo’s generational base, predominantly working-class, also remains the least moved by his many scandals.

Except for one…

Perhaps, Andrew Cuomo’s base of senior voters — after months of relentless television advertisements about the former Governor’s controversial order (later revoked) to return COVID-positive patients to nursing homes, in addition to the subsequent coverup of said death toll — eventually ask themselves, and one another, “could that have been me?”

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Zohran all day.