Zo-mentum

Breaking down the most exciting campaign in New York City

“There is not an ideological majority in New York City.” — Zohran Mamdani

My grandfather — born and raised in Brooklyn during the Roaring Twenties, and soon thereafter, the Great Depression — would regale my father with stories of the days when Mayoral hopefuls campaigned on slogans like, “I’ll make sure the subway never costs more than a nickel.”

My Dad, who lived in New York for forty years, was never particularly animated by local politics, especially compared to his son. However, like the best of fathers, if I’m interested in something, he’s interested too. So, naturally, he has been closely following the New York City Mayor’s race — albeit from afar — for perhaps the first time in his entire life.

Lately, he’s been asking a lot about Zohran Mamdani.

Like you, he’s seen Mamdani’s viral videos (rave reviews), watched his interview on Breaking Points, and, of course, read my Substack (and Ross Barkan’s).

“Is this enough to win?”, he asks — the question on everyone’s mind.

“Maybe,” I respond. “So far he’s hitting all of the right notes. But, to reach the 50% majority in ranked-choice-voting, not only would he need to have incredible voter turnout among his base, but people like [insert affluent Manhattanite] would have to choose him over Andrew Cuomo.”

“If I’m Mamdani,” he begins, “I try to develop some unique issues that don’t alienate my base, but can transcend ideology, because he’s capable of energizing all kinds of people. If the union bosses don’t back him, he should go straight to the rank-and-file voters. He needs to reach the people — before AIPAC does.”

“Well, he’s already doing that. Fast & Free Buses, for instance, all the most trafficked bus lines are in the outer boroughs. The “Rent Freeze” too, the neighborhoods with the most rent-stabilized tenants are in the Bronx. I mean, there are two million rent stabilized tenants in New York—”

“TWO MILLION People?!?!”

“Yes—”

“And, NO ONE has thought to do this before???”

“Well, not like this… Already, the urban professional class is a strong voting bloc, everyone under 40 is voting for him. I’m seeing my normie friends from college post his videos on their Instagram stories (I didn’t even know some of them moved to NYC). He’s already got thousands of volunteers, that’s Bernie and AOC levels of enthusiasm — and it’s not even springtime! Zohran’s also investing a lot of time and money trying to organize South Asian, Muslim, and Arab voters behind his campaign, but few can predict how it will shape the outcome, in part, because it’s never been done at this scale before. Basically, he’s building a coalition of market-rate renters and the rent-stabilized. Trump has destabilized the Democratic Party, and a lot of the old guard has been slow to adjust. The city’s political institutions are weak, and the anti-Cuomo lane is wide open. Even if he doesn’t win this year, his coalition — urban left-leaning professionals, South Asians, and Muslims — are among the fastest growing demographics in New York City…

Maybe I should just write an article about this?”

Attention Economy

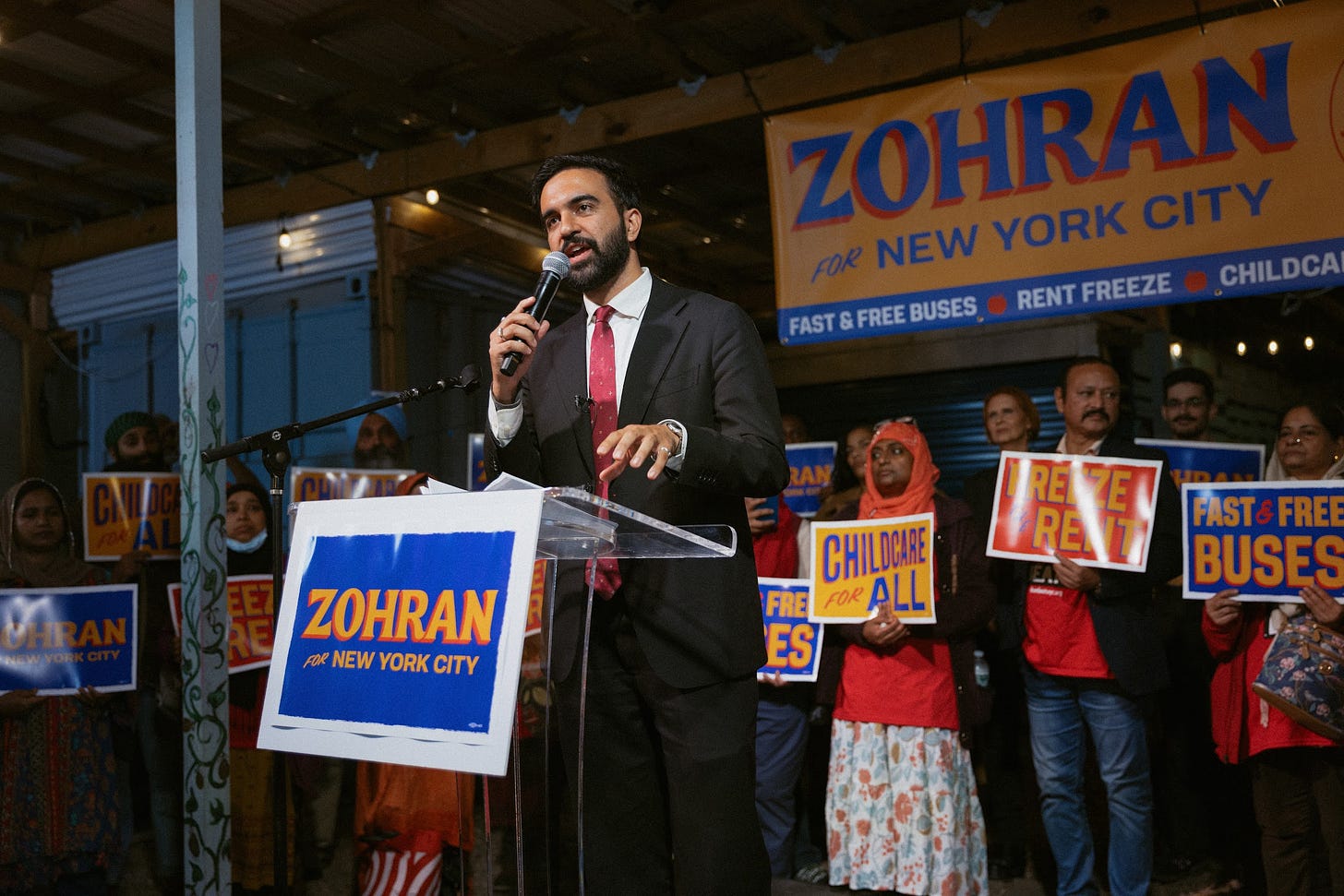

If you’ve been anywhere on the Internet — Twitter, Instagram, TikTok — over the past five months, chances are high you’ve seen Zohran Mamdani, the democratic socialist lawmaker from Queens running to be the next Mayor of New York City.

His viral videos — “man-on-the-street” style interviews with Trump voters, halal cart workers, and first-time donors to his campaign — are the envy of the local political ecosystem (inspiring several, less successful, like-minded efforts). The charismatic millennial, caught eating a burrito on the subway (with a knife and fork no less), cannot even break fast during Ramadan without millions of people taking notice. After confronting border czar Tom Homan, Mamdani’s campaign raised nearly a quarter-of-a-million dollars in the ensuing twenty-four hours. Zohran Mamdani remains everywhere, or so it feels – all without missing a single day in Albany.

When Zohran launched his campaign last October, I wrote that, “Mamdani’s energy: his drive, willingness to experiment, and capacity to inspire, seared into the memories of those who saw him operate in Bay Ridge, could turn what has thus far been a relatively sleepy affair — given the stakes — upside down, delivering a political crusade New York City has not seen in the modern-era. In a race where viability boils down to exposure and press coverage, it is not far-fetched to foresee a scenario where Mamdani vacuums a lionshare of that oxygen — starving rivals looking to climb the polling ladder.”

A bullish prediction at the time, that has nevertheless been exceeded.

In the age of the Attention Economy, Zohran Mamdani is well-suited to the relentless hustle of round-the-clock interviews, podcasts, and social media posts that have elevated the next generation of Democrats, from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to Jasmine Crockett. In New York City, disaffected Democrats, particularly younger generations — whose political upbringing was defined by the War on Terror, Barack Obama’s Hope and Change, the Great Recession, Bernie Sanders’ Presidential campaigns, the COVID-19 pandemic, and two terms of Donald Trump — have gravitated to Mamdani, a believer in Free Buses and Free Palestine.

And, while Andrew Cuomo’s entrance has consumed much of the proverbial media oxygen necessary for a lesser-known candidate to breakout, “Zo-mentum” has not only failed to decelerate, but kicked into high-gear.

However, press hits and viral videos do not represent the beginning, nor the end, of the burgeoning momentum of Mamdani’s campaign, now nearly five months removed from launch, with little more than three months until June’s Democratic Primary.

“The biggest misconception of our campaign,” Mamdani said, “is that it lives online.”

Indeed, by every available metric, Zohran Mamdani’s campaign has thrived in the real world.

The Social Network

As traditional political networks have atrophied, culminating in the slow-death of “machine” politics, many New Yorkers have embraced the anti-establishment, class-conscious, progressive politics popularized by Bernie Sanders. This development, spurred by the increased migration of early-career professionals — increasingly priced out of Manhattan — into Brooklyn and Western Queens, has not only toppled ethnic fiefdoms and seized power, but reshaped the political character of several neighborhoods. Masses of volunteers, the foot soldiers necessary to prevail in low-turnout Democratic Primary elections, no longer come from the union hall or the Democratic club, but from ideological-based networks, like the Democratic Socialists of America and Working Families Party.

Astoria, once a predominantly Greek and Mediterranean enclave in Northwest Queens, is emblematic of this shift. Mamdani, elected to represent the neighborhood in the state legislature five years ago, defeated incumbent Aravella Simotas, an ally of the once-powerful Queens County Democratic Party, long the de-facto broker that hand-picked winners, and buried losers. Voters took kindly to his disavowal of donations from real estate developers and police unions (his opponent, did not); while embracing Mamdani, not as another run-of-the-mill “progressive,” but an unabashed democratic socialist. Symbolically, Zohran launched his campaign the same day Bernie Sanders hosted a rally with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in Queensbridge Park. Mamdani’s victory was aided by both the micro: a steady increase in left-leaning residents, some of whom successfully organized (for multiple years) while the local, nascent political machine crumbled; and macro: the near-term apex of both progressive popularity and civic engagement, social forces catalyzed by George Floyd’s murder, the upcoming Presidential Election, and ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

While the political landscape shifted under President Joe Biden, the micro-conditions that underwrote the left’s burgeoning political power showed few signs of abating. Already, in a Democratic Primary, there were more votes to be had in places like Astoria than several of the outer borough, working-class neighborhoods that once forecasted victory in a citywide election. Indeed, the evolution of these left-leaning, lively neighborhoods into a political bloc — spanning Alphabet City, Greenpoint, Williamsburg, South Slope, Prospect Heights, Bushwick, Ridgewood, Long Island City, Sunnyside — capable of not only seizing power in individual neighborhoods, but serving as the coalition bedrock for a top-tier Mayoral candidate, would have been inconceivable even ten years ago.

Here, where greater than half of the Democratic electorate is under the age of forty-five, the “generational aspect” of Mamdani’s campaign shines through. Indeed, to exit the subway during rush-hour on Jefferson Street in Bushwick or Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg, is to be surrounded by hundreds of people of every race and religion — all of whom appear to be younger than 40.

For generations, outer borough neighborhoods across New York City were split between immigrants (born outside of the United States) and natives (born in New York State). Today, there is a growing contingent of “transplants,” those born in the United States, but outside of New York. The vast majority have a college-education and make their living in white-collar industries; many of the latter left the offices in March of 2020, never to return. The spectrum of their class composition is considerable: the most fortunate own their apartments, having ridden the stock market back from the recession’s nadir, either in recently developed pseudo-luxury buildings or rehabilitated co-ops with surprisingly low maintenance fees; however, for the vast majority, homeownership remains out-of-reach, at least in close proximity to their current habitat. They value the authenticity of an outer borough neighborhood, a feeling they wouldn’t get in the sterile urban core, but nonetheless appreciate the amenities that come with the influx of young urban professionals. With time, many from their personal networks (college friends, work colleagues, dating circles) have moved there too. Rent, always rising in enclaves where demand far exceeds supply, remains a top-concern; whereas Crime, relatively low and rarely surpassing petty theft, is not.

Come June 24th, Zohran Mamdani is not only favored to sweep this cohort, but usher in record-voter turnout. Since 2018, each aforementioned neighborhood has elected at least one democratic socialist to either city or state office (oftentimes both). Along these blocks, in a matter of months, “Zohran” is poised to become a buzzword on par with Bernie and AOC.

Furthermore, Mamdani has cultivated this support — beyond a vote at the ballot box, a like on social media, or a volunteer shift at a canvass — into an unrivaled small-dollar donor base, which has helped Mamdani raise more money, including the upcoming matching funds disbursement, than any other candidate for Mayor. In fact, Mamdani has nearly eighteen thousand individual donors from the five boroughs (Brad Lander, the next closest, has slightly more than six-thousand). And, since entering the race in late October, Zohran has the most donors in 121 of New York City’s 178 ZIP codes (including all filing periods, Mamdani still leads the donor count in 91/178 ZIPs).

And, while the financial spectrum of New York City’s ZIP codes is indeed a Tale of Two Cities, Zohran Mamdani, nonetheless, has the most individual contributors in both ZIP codes where donors are measured in the hundreds (Morningside Heights, Lower East Side) or the dozens (Bedford Park, East New York).

Historically, only a handful of neighborhoods in Manhattan and Brownstone Brooklyn dominate the fundraising circuit of the five boroughs. Four years ago, approximately half of all New York City-based money raised in the Mayoral race came from only five of the city’s sixty-three Assembly Districts (all of which were in Manhattan); while greater than two-thirds of all dollars came from the top-ten.

Brad Lander, the former Council Member for a series of affluent, progressive neighborhoods west of Prospect Park, has raised almost half-a-million-dollars alone from Windsor Terrace, Park Slope, Carroll Gardens and Brooklyn Heights (with some individual blocks exceeding five-figures). Andrew Cuomo has consolidated the old money that lines the Upper East Side from Park Avenue to Central Park, raising between ten and fifteen thousand dollars per election district throughout this lucrative corridor, which once belonged to Eric Adams. The well-documented fundraising shortcomings of Jessica Ramos and Michael Blake, both from low-income neighborhoods in the Bronx and Queens respectively, are due, in part, to their struggles raising even five-figure sums from the city’s wealthiest enclaves.

This is not to say that there is only one way to competitively raise money or amass matchable donations. Scott Stringer, despite raising his highest totals from Manhattan’s West Side, has nonetheless amassed impressive support from Chinese donors in Southern Brooklyn and Eastern Queens. Before indictments and scandals froze his fundraising, Eric Adams banked several large contributions from Orthodox Jews in Midwood, Sephardic Jews in Sheepshead Bay, and Russian Jews in Manhattan Beach; not to mention the wealthy, white ethnic communities with coastal mini-mansions (like the Anora mansion), in Mill Basin, Malba Estates and Bay Ridge’s Harbor View Terrace. Adrienne Adams, having only raised money for six days, solicited noteworthy contributions from both her native Southeast Queens and the Satmar Hasidim of South Williamsburg. Nonetheless, the largest hauls, all but necessary to compete at the highest level, have almost exclusively come from Manhattan’s toniest enclaves.

However, such is not the case for Zohran Mamdani.

Mamdani has raised more money from Astoria, Queens than the Upper West Side of Manhattan; more from the hipster-East Village than the classy-West Village; more from gentrifying Bedford-Stuyvesant than professional-class Park Slope; more from once burnt-out Bushwick than the old moneyed Upper East Side.

Across several vast stretches of Brooklyn, one could literally walk for miles without passing a single precinct with less than a dozen contributors to Zohran Mamdani.

This fervent base, desperate for something and someone to believe in, has helped catapult Mamdani, according to multiple polls, into second-place behind the early frontrunner, former Governor Andrew Cuomo.

The North Star

“I’m most proud of our breadth of support, which stretches beyond self-identified progressives and socialists. There is not an ideological majority in New York City, but a majority who feel left behind by the economic policies of this Mayoral administration, and of politics today.”

— Zohran Mamdani

While Mamdani has thus far trained his fire on Andrew Cuomo, not to mention the disgraced (but increasingly irrelevant) incumbent, Eric Adams, the majority of the insurgent’s energy is spent relentlessly championing an economic message, a thesis that New York City’s greatest crisis is not one of runaway crime or managerial incompetence — but of crippling costs-of-living, from housing to childcare. The broad scope of his platform — including freezing the rent for every rent-stabilized tenant, making buses “fast and free,” municipality-owned grocery stores (one in each borough, targeted towards food deserts) — stretches beyond the confines of traditional left-liberal policy pillars, and explicitly targets working-class communities. In an age of hedging and double-speak, Mamdani’s platform is well-defined and unique, while representing the unabashed economic populism and class-based agenda many have been clamoring for since Bernie Sanders ran for President.

“I think the thing that New Yorkers hate more than a politician they disagree with is one that they can’t trust.”

Indeed, the neighborhoods with the highest concentration of rent-stabilized apartments are low-income, predominantly Hispanic communities in Upper Manhattan (Washington Heights, Inwood) and the Bronx (Morrisania, Fordham, Tremont) adjacent to Crotona Park. Much of the same can be said for bus ridership — disproportionately seniors, people with disabilities, and families — with nine of the ten most patronized bus routes confined to Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Food Deserts — East Tremont, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Sunset Park — with alarmingly high bodega-to-supermarket ratios, are unsurprisingly concentrated in working-poor, previously-redlined neighborhoods.

Traditionally, candidates for Mayor (and their consultants/advisors) have viewed New York City’s Democratic electorate through the prisms of polling: Ideology, Age, Race, Class, and Borough — failing to capture Gotham’s infinite nuance. Analysis rarely extends to the neighborhood-level, let alone individual blocks, buildings, and commuting patterns. Previously, no Mayoral candidate courted rent-stabilized tenants as a “voting bloc,” despite the heterodox cohort totalling close to two million residents in New York City. Now, almost every candidate forum includes a question about a “rent freeze” (Jessica Ramos and Michael Blake have also pledged their support). Similarly, to the extent car owners are considered a reactionary contingent in need of placation (evidenced by the Congestion Pricing saga), while proponents of cyclist and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure enjoy influence with the government and lobbyist class, little is said for the hundreds-of-thousands of daily bus riders.

However, reaching these less politically-engaged voters — many of whom are registered Democrats, but nonetheless infrequently participate in Primary elections — is no easy feat for a three-term state representative.

For one, they are “less online,” a function of occupation, lack of free time, and age. And, when they are, their digital footprint is different: YouTube, WhatsApp, and Facebook are well-represented, while Television (astronomically expensive to advertise on in the New York media market) reigns supreme. Despite New York City, as a whole, remaining statistically as safe as ever, many working-class and low-income neighborhoods are still reckoning with fallout from the pandemic. Upticks in random violence, spurred by an evolving mental health crisis, have coincided with a (no longer) underground economy of sex-work and drug-dealing rising onto the street-level. Backlash to new immigrant groups, coupled with diminished quality of life, led to pronounced inroads for Donald Trump among Hispanics and Asians of all socio-economic classes and national origins. Much of these gains came from neighborhoods where there is little resembling a local political infrastructure, beyond the skeleton of an atrophied Democratic machine, in addition to a handful of social service not-for-profits. Indeed, throughout ZIP codes where two-thirds of households make less than fifty-thousand dollars, political participation is a luxury many cannot afford. Four years ago, the majority of those who actually did vote (in many Bronx neighborhoods, Democratic turnout fell below nineteen percent), defaulted to Eric Adams, the former police officer who consistently spoke of public safety.

Nonetheless, many remain tethered to New York City: unwilling, for their entire life has been tied to the five boroughs; OR unable, owed to a rent-controlled apartment or housing voucher — to leave. A lifetime in New York City brings a network of its own (block associations, parent groups, houses of worship), and thousands of interactions with all branches of city bureaucracy. At a time when Democrats are hemorrhaging support among “less engaged voters,” can Zohran Mamdani, with his rare blend of politics and persona, move those far beyond the narrow parameters which traditionally govern political participation, and shock the world on June 24th?

Many may feel dis-affected, but few are dis-invested in the future of New York City.

Sense of Belonging

“There is a representation of sets of voters that typically, in the very best scenario, have been erased from the political fabric, and in the worst scenario, have been persecuted by the political system in the city.”

Zohran Mamdani was nine years old on September 11th, raised in a New York City increasingly hostile to Muslims, Sikhs, and Arabs; where those who wore turbans and hijabs were targeted for hate crimes. At Bowdoin College, he co-founded the university’s first Students for Justice in Palestine chapter. A graduate of Bronx Science, he developed an affinity for John Liu, the first Asian candidate to run for Mayor, who supported a $15 minimum wage and legalizing marijuana. Mamdani’s first experience knocking doors came in a plurality-Asian, Eastern Queens district — miles of working-and-middle class residential neighborhoods thirty minutes by bus from the closest subway station. The man he made the pilgrimage for, Ali Najmi, is now Mamdani’s election lawyer. Months into Donald Trump’s first term, Mamdani found himself in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, moved by Khader El-Yateem, a Palestinian-Lutheran Minister running for City Council. While the race acquainted Zohran with NYC-DSA, and the cadre of volunteers who showed up day-in-and-day-out, night-after-night, to canvass for their endorsed candidate, Mamdani developed a closeness with El-Yateem, known to many as “Father K” for his loving, paternal nature. In “Father K” — a man raised in the West Bank, who survived torture in an IDF prison, and eventually opened a parish that became a conduit for Arab immigrants navigating their new lives in the five boroughs — Zohran saw someone worth believing in: “My life was transformed by Khader El-Yateem. He gave me a sense of belonging in a city that I had always loved, but one in which I had not known if my politics had a clear place.” Now, running for Mayor, Mamdani reflected to the author, “I hope this campaign offers the same chance for New Yorkers to see themselves in our campaign and our message.”

Even when El-Yateem narrowly lost (he moved to Florida the following year), Mamdani kept organizing Arab communities in Bay Ridge — sleeping on couches, floors, wherever he could — eventually as Campaign Manager for journalist Ross Barkan. Here, Zohran was not so much focused on persuading voters, but creating them. “I knew, back then, he’d run for office someday,” Barkan said. Two years later, Mamdani was elected to represent Steinway Street in Astoria, one of the Islamic enclaves illegally surveilled by the NYPD under the administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg. One of Mamdani’s campaign promises was to end medallion debt for taxi drivers, an epidemic that led to a flurry of suicides, a disproportionate number of whom were South Asian men. Over coffee, Zohran shared their plight with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, who, together, tag-teamed City Hall — Schumer behind-the-scenes, Mamdani leading a hunger-strike — to adopt a beneficial debt relief deal. On day fifteen of Mamdani’s hunger strike, an agreement was reached between the City, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, and Marblegate, the largest taxi medallion lender in the industry.

“[Zohran] Mamdani was always there, delivering fiery speeches and trying to pitch the story to journalists who felt the issue had already been covered to death. ‘The grief, trauma, suffering, exploitation, the predatory nature of this entire crisis—that wasn’t new,” Mamdani told me. ‘The real struggle was how do we break through that.’ To draw more attention, he stopped going to his office and did his work from the protest camp. ‘If someone wanted to meet me about any concern, they’d have to first come and see and hear the sound of the taxi drivers’ struggle.’” (The Nation)

As a lawmaker, Mamdani voted against maps that splintered South Asian communities, long gerrymandered. Last Spring, he introduced the Not On Our Dime bill, which (if passed) “could strip New York nonprofits of their tax-exempt status if their funds are used to support Israel’s military and settlement activity.” While many Democrats fear retaliation from the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), Mamdani never flinches when saying “genocide.”

“Zohran Mamdani, a social progressive of Shia background, has been warmly welcomed at a different Sunni masjid every Friday in areas where Donald Trump made gains, debunking the tired and racist myths that Muslim voters are purely animated by sectarianism and/or social conservatism.”

Every Friday, Zohran Mamdani can be found at a different Mosque, taking part in the weekly Yawm al-Jum'ah Prayer. On his campaign website, there is a separate tab for Ramadan Events, from the Al Mustafa Islamic Center in Brighton Beach to the “Bronx Bangla Bazaar” in Parkchester. Before the February 14th deadline to switch party registration, volunteers accompanied Mamdani to his weekly Masjid visits, re-registering Muslim voters outside after prayers concluded and parishioners departed. In his telling, one cannot expand the left coalition in New York City without bringing Muslim, South Asian, and Arab voters into the fold.

However, activating and empowering a segment of the electorate, where little political scholarship already exists, presents a challenge. For one, census data does not ask about religious identification. As such, experts cannot even agree on the size of New York City’s Muslim population, with estimates ranging from several hundred thousand to one million. South Asians, even when compared to other demographic groups in New York City, are “highly diverse in terms of language, religions and faiths, and cultural practices.” A comprehensive 2023 report, published by the City University of New York, concluded: “Our understanding of Muslim New Yorkers is poor—Estimates of the Muslim population in New York City vary and their demographic and political characteristics are poorly understood. The city government should prioritize research on this growing population, especially research that aims to understand the extent to which the political preferences of the various ancestral groups that practice Islam in the city overlap.”

Yet, from what we do know, Mamdani might be the person to do it. Four years ago, more Muslims voted for Eric Adams than any other candidate for Mayor, while many South Asian enclaves, from Hillside Avenue to Little Punjab, also backed the Brooklyn Borough President. Both Muslims and South Asians, not mutually exclusive, are among the youngest and fastest growing demographics in New York City. In fact, Bangladeshis, the largest ancestry of New York City’s Muslim population, saw their voting-age-population increase by sixty-six percent from 2010 to 2020. Exceeding one-hundred thousand residents (over half of whom are registered to vote), Bangladeshi voters have a track-record of supporting progressive candidates, like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in both Primary and General elections. And, since the beginning of the Israel-Hamas war, as the Presidential administrations of Joe Biden (and later, Donald Trump) continued to placate the worst impulses of Benjamin Netanyahu, many have felt politically unmoored from the Democratic Party — leading to an increased in Republican raw votes and write-in ballots, despite lower overall turnout — across Muslim, South Asian and Arab precincts last November.

Can Zohran Mamdani, one of the few local officials to consistently call for a Ceasefire in Gaza, bring these voters back into the Democratic Party?

To bridge the information gap, Mamdani is hoping to harness the full potential of grassroots politics — door-knocking, signature-gathering, and tabling — bolstered by an average of one-hundred-and-twenty-five new volunteers per day. This vast operation, rooted in the physical rather than the digital, has little precedent in the modern era of New York City.

In 1965, John Lindsay opened more than two-hundred storefronts across the five boroughs, helping the liberal Republican dethrone the Democratic bosses. Two decades later, the movement that led to the triumph of David Dinkins spent years registering Black and Latino voters in Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and the South Bronx (bolstered by Jesse Jackson’s Presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988), before thousands of volunteers helped the “Rainbow Coalition” prevail against Ed Koch and Rudy Guliani. Now, thirty-five years later, can a volunteer army once again stoke a historic upset?

A cursory review of Mamdani’s volunteer page reveals a plethora of daily events, spanning vast stretches of the five boroughs. By the author’s count, the Mamdani campaign administered seventy-nine separate canvasses across thirty-three different neighborhoods — in one week alone! On consecutive nondescript, chilly weekends in February and March, Zohran was already drawing hundreds willing to donate their time to his insurgent bid. And, while canvassers frequently traffic the progressive left’s lively hotspots, their travels — from the Upper West Side to Jamaica, Queens — span the spectrum of the coalition Mamdani is painstakingly working to assemble.

Although almost every viable campaign will access the matching funds limit, no other outfit will come close to matching Mamdani’s people-power. As a first-time candidate for higher office, Zohran’s thousands of volunteers represent one of his greatest competitive advantage.

This comes at a time when Democrats, reeling from November’s defeat, are questioning the efficacy of a strong ground-game in today’s media-driven environment. If Zohran Mamdani’s campaign is, in part, a test of how far social media prowess can elevate a charismatic underdog — it will also provide evidence of canvassing’s effects, not only in persuading voters to rank Mamdani high on their ballots, but to show up to the polls at all.

Against Andrew Cuomo, will it be enough?

Liston vs. Ali

If Zohran Mamdani dominates both air and ground, Andrew Cuomo’s domain is the middle.

The former three-term Governor’s polling strength, routinely twenty-points ahead of the next closest rival, is owed to a form of “latent incumbency,” as articulated by journalist Will Bredderman, and a familial dynasty spanning half-a-century. For months, Cuomo teased his potential entrance, all while “lining up support from stakeholders—many of whom don’t really control that many votes—to create the appearance of invincible and inevitable momentum.” Despite a tumultuous relationship with African-American power brokers early in his career, Cuomo repaired his standing among the Black political establishment — to the extent where New York’s Black community served as his political firewall during the desperate final months of his time in the Governor’s Mansion. With Eric Adams flirting with President Trump and Border Czar Tom Homan, Cuomo has already surpassed the disgraced incumbent among Black voters, while peeling away many of the Mayor’s staunchest allies instrumental to his victory four years ago, most notably the Brooklyn Democratic Party. Undoubtedly, Andrew Cuomo desires a “Rose Garden” campaign — almost no questions from the press and few public appearances — and to coast into City Hall on name recognition alone.

However, Cuomo’s comeback equation is not so simple. Labor leaders and segments of the Black political establishment, rather than accept the former Governor’s inevitability, instead drafted City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams into the race at the eleventh hour. The New York Post, once Eric Adams’ secret weapon, eviscerated the former Governor following his sit-down with the Editorial Board. Already vulnerable, there is a coordinated effort (D-R-E-A-M) solely designed to stop him. His roster of endorsements from current elected officials remains underwhelming. Andrew Cuomo’s political apex, the many months of pandemic briefings that captivated the nation, came when he represented the calm antidote to Donald Trump’s chaos. Now, the former Governor has few criticisms of the President. In fact, Cuomo even touted their collaboration in his inaugural campaign video, while criticizing Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg for his “politically motivated” prosecution of Trump.

At a time when Democrats are begging for a fighter, how much fight does Cuomo have left? Could Andrew Cuomo be Sonny Liston?

In 1964, Sonny Liston was the heavyweight champion of the world. With strength and reach, he was feared as one of the most intimidating men in the history of combat sports, and set to defend his title against a little-known opponent. The heavy favorite, 43 of 46 sportswriters picked the champ to win by knockout, while odds makers gave Liston 8:1 odds to win. Overconfident, Liston trained minimally for the fight and pushed forward despite an injury to his left shoulder. However, when the opening bell rang, and Liston tried to land a glove on his foe to end the fight quickly, as he had done so many times before — he couldn’t. His opponent was agile and fast moving around the ring, to the point where the champ struggled to connect. Even when he did, Liston couldn’t press his advantage home. His opponent, oftentimes on the defensive, could hit back quickly, delivering a “remarkably fast series of combinations” at a moment’s notice. One such flurry caused a cut under Liston’s left eye, which eventually required eight stitches. It was the first time in his career that Liston had been cut. At the conclusion of the sixth round, an injured and exhausted Liston quit.

His opponent, Muhammad Ali, then known as Cassius Clay, became the new heavyweight champion of the world.

Before midnight on Wednesday, I caught up with Zohran on the phone for a couple minutes before he went to bed. As our conversation wrapped up, I couldn’t help slipping in one final question:

“Was there a moment it all became real for you? Not only running for Mayor, but actually becoming the Mayor.”

It was an imperfect inquiry, asked at the end of another sixteen hour day for Mamdani. Nonetheless, Zohran pursued my query with the same thoughtfulness and reflection commensurate with the type of campaign he has run thus far. After pausing to scan through months of highlights, he delivering his answer:

“I finished speaking at a mosque in Southern Brooklyn, and an uncle came up afterwards and showed me a photo of Eric Adams, four years ago, standing in the same spot I was now.”

“I voted for him last time,” he told me, “now I’m voting for you.”

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Thanks for this write-up!

I get that millennials and zoomers are excited. You clearly are. But he is still firmly in the tongue-bath stage from him media allies and hasn't taken any heat yet. I see nothing here about whether a far-left anti-Israel candidate can win in the city with the largest Jewish population in the world. We'll see! I have my doubts.