Andrew Cuomo's Last Chance

The former Governor of New York, who resigned in disgrace less than four years ago, is the early frontrunner to be New York City's next Mayor

The Pride Before The Fall

Less than five years ago, Andrew Cuomo was at the apex of Democratic Party politics.

Prior to 2020, Cuomo was already a well-known Governor of a deep-blue state. He was two years removed from convincingly winning a third term, and appeared on pace to coast to a fourth in the coming years — a feat which would surpass the heights of his father, Mario Cuomo, who served as Governor of New York from 1983 to 1994. He had been married to a Kennedy, counted the Clintons as close allies, and boasted several infrastructure and legislative accomplishments to his name; chiefly, the early passage of marriage equality and revitalization of La Guardia Airport and Moynihan Train Hall. An unauthorized biography, released five years earlier, presented Cuomo as a dark-horse Presidential contender in the mold of Lyndon Johnson. Elected in 2010, his political posture was never fixed; beginning his Albany tenure as a “cost-cutting fiscal centrist taking on the public-employee unions,” before proudly proclaiming himself a “pragmatic progressive” as the zeitgeist moved in the latter’s direction. Cuomo had weathered several scandals that would have sunk weaker politicians: his controversial decision to disband the Moreland Commission, right as the anti-corruption outfit was turning their attention to the Governor’s administration; the indictment and sentencing Joe Perocco, his former campaign manager and longtime confidant, for bribery and fraud (his conviction was overturned in 2023); tacit support for the Independent Democratic Conference, which gave defecting Democrats and Republicans control of the State Senate, holding progressive legislation hostage for several years; and the swift, predictable alienation of well-respected MTA chair, Andy Byford, followed by the infamous “Summer of Hell” on New York City’s subways. He had almost no friends (for Andrew Cuomo was feared, not loved), no residence outside of the Governor’s mansion (his identity was, in almost every sense, his power), a communications team that operates “with baseball bats,” and an air-tight inner-circle (prone to turnover due to Cuomo’s “unrelenting” demands). Vice President Joe Biden said his “favorite thing about the Governor” was his “tremendous balls.” His style was not rooted in cultivating allies, but dominating them — eliciting comparisons to Machiavelli’s Prince and master-builder Robert Moses. There was little doubt that Andrew Cuomo was the most powerful man in New York State.

However, as COVID-19 devastated New York, Andrew Cuomo’s daily pandemic briefings catapulted the Governor to heights previously unknown. While Cuomo rattled off the latest statistics on infections, hospital beds and deaths — no less than appointment viewing across the tri-state area — he became, overnight, the liberal antidote to President Donald Trump. All told, almost sixty million people had tuned into one of his Coronavirus briefings. The telegenic Andrew Cuomo even won an Emmy — an honor never bestowed onto Courtney Cox, Hugh Laurie, or Steve Carrell. A lucrative book deal, exceeding five million dollars, was awarded to the charismatic Governor for chronicling his efforts combatting the pandemic. Superfans bought “Cuomosexual” tee-shirts. Media observers daydreamed about replacing the reclusive Joe Biden with the omnipresent, fear-assuaging Cuomo to lead the Democratic Presidential ticket in November. Regardless, New York’s Governor would be a top contender in four years when Biden inevitably retired.

However, this moment, an apex unrivaled in the Trump era, proved fleeting, for within it were the seeds of the Governor’s swift demise. The following summer, Andrew Cuomo resigned in disgrace, an astonishing fall from grace with little modern precedent, an “Icarus-like arc for a leader convinced of his own hype and indestructibility.”

The Loss of Power

“Mr. Cuomo is an object lesson on the dangers of kicking people on the way up.” (The New York Times)

On December 13th, 2020, former aide Lindsey Boylan publicly accused Andrew Cuomo of sexual harassment, writing, “[Governor Cuomo] sexually harassed me for years. Many saw it, and watched… I hate that some men, like [Cuomo] abuse their power.” Specifically, Boylan claimed Cuomo had asked her to play “strip poker” during a flight on a taxpayer-funded private jet; and later, gave her an unwanted kiss in his Manhattan office.

Publicly, Cuomo denied Boylan’s charge, but asserted his “[belief that] any woman has the right to come forward.” Privately, the Governor and his team scrambled, retaliating against Boylan by leaking her confidential personnel files to the media. Cuomo himself called “at least six former aides with questions related to Boylan, including whether they had been in contact with her,” a maneuver which some felt was an effort to intimidate them. In the following days, Cuomo’s aides circulated a “disparaging” open-letter to former staff members “attacking” Boylan’s credibility and linking her to Donald Trump. The letter, later reviewed by The New York Times, was never released.

The extensive efforts undertaken by the Cuomo administration to discredit Boylan revealed the depth of their fears. For, unbeknownst to the outside world, “at the time, officials in the Governor’s office were aware of another sexual harassment issue involving Mr. Cuomo that had not yet become public.”

Lindsay Boylan’s allegations, which made national news and rocked the New York political world, marked the beginning of the end for Andrew Cuomo.

Already, the mythos of the Cuomo administration’s unimpeachable handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, efforts that were once lauded across the nation, were beginning to crack. Specifically, the Governor’s order, which came at the height of the pandemic (March 25, 2020), that all New York State nursing homes must accept residents that are “medically stable” (rescinded on May 10th), was under scrutiny. The following January, the Office of New York State Attorney General Letitia James issued a report which “found that nursing home resident deaths appear to be undercounted by DOH by approximately 50 percent.” Soon thereafter, Melissa DeRosa’s private apology to state lawmakers, where the Governor’s top aide admitted to manipulating the nursing home death toll (dishonesty committed, in her telling, to avoid President Trump weaponizing the issue against Cuomo), was leaked to the New York Post, which led to the FBI launching a preliminary investigation into the Cuomo administration's handling of nursing home data. Quickly, the administration revised their long-term care resident death toll from 8,500 to 15,000. On March 4th, The New York Times reported that the Governor’s most senior aides “rewrote” a report published the previous July, “taking out” the higher death toll provided by the State Health Department.

Crucially, this deliberate intervention coincided with Andrew Cuomo seeking a lucrative book deal, for which an advance of over five million dollars was eventually procured, detailing his experience leading New York through the pandemic. In the fall of 2020, as Cuomo was touting the release of his memoir, New York experienced a second wave of the virus. According to an independent investigation commissioned by the New York State Assembly’s Judiciary Committee the following year, the Cuomo administration “forced state employees, from junior aides to senior officials, to work on ‘American Crisis,’ urged a state ethics board to fast-track approval of the book deal, and downplayed the amount of money the former governor stood to make from the book’s publication.”

On February 27th, Charlotte Bennet, a former executive assistant and health policy advisor to the Governor, became the second woman to accuse Cuomo of sexual harassment. According to Bennet, when the two were alone in the Governor’s State Capital office, Cuomo asked if she “had ever been with an older man.” Soon thereafter, a former Obama staffer, Anna Ruch, accused Cuomo of making unwanted advances (“can I kiss you?”) towards her at a mutual friend’s wedding two years earlier. In an image worth one thousand words, a photograph emerged of Cuomo clutching Ruch’s face with both hands, amidst her nervous expression. Less than one week later, former aide Ana Liss accused the Governor of touching her lower back without consent. The same day, Karen Hinton said Cuomo had hugged her “inappropriately” in a hotel room twenty-years ago (Hinton was one of Cuomo’s press aides when he ran the Department of Housing and Urban development). Three days later, an anonymous member of the Governor's Executive Chamber staff, later revealed as Brittany Commisso, told the Albany Times Union that Cuomo touched her inappropriately; and that, following Boylan’s allegation, the Governor urged her to stay quiet.

“I was a liability, and he knew that. He was definitely trying to let me know, ‘It would be in your best interest [to keep quiet].’ ... I know his look and I know how intimidating he can be. He wanted to get a message across to me… Near the end of [our conversation], he looked up at me and he said, ‘You know, by the way, you know people talk in the office and you can never tell anyone about anything we talk about or, you know, anything, right?’ I said, ‘I understand.’ He said, ‘Well, you know, I could get in big trouble, you know that.’ I said, ‘I understand, governor.’ And he said, ‘OK.’”

Time and time again, Andrew Cuomo not only vehemently denied the charges against him to the press, but to his increasingly small cadre of advisors, many of whom were women. Lis Smith, a polarizing political consultant best known for her role leading Pete Buttigieg’s Presidential campaign, wrote that in the aftermath of the Times Union story, she heard “genuine fear” in Andrew Cuomo’s voice — for the first time.

Less than two weeks later, Alyssa McGrath became the first current aide to come forward and detail the culture of sexual harassment in the Governor’s administration. Brittany Commisso and Alyssa McGrath spoke regularly, particularly about their interactions with the Governor “because an informal policy prohibited them from speaking to anyone outside the executive chamber about Cuomo.” Aware of this dynamic, Cuomo, according to McGrath, instructed the former to not tell the latter about the aforementioned alleged incident. “He told [Commisso] specifically not to tell me,” McGrath told The New York Times.

With each allegation, Andrew Cuomo’s future as Governor of New York grew more tenuous.

“Mr. Cuomo could not contain the scandal with his usual, and typically effective, mix of threats and charm. Indeed, the persona that made him a political matinee idol during the pandemic — that of a paternal, and sometimes pugnacious, micromanager — seemed ill-suited to addressing the emotionally charged allegations of sexual harassment against him, some made by women who were not even half his age.”

Already, the majority of New York State’s congressional delegation, including both United States Senators, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand, had called on the Governor to step down, joining State Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins and over fifty state lawmakers. State Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie also began a wide-ranging impeachment investigation, that spanned the sexual harassment allegations, lucrative book deal, and questionable handling of nursing homes. Time was running out for Andrew Cuomo.

Undaunted, the Governor insisted, “I am not going to resign.”

With his political future hanging in the balance, Andrew Cuomo clung to his allies across the Black community, many of whom were less inclined to shun the besieged Governor; a crisis playbook borne out of the survival of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, who weathered widespread calls for his resignation following the emergence of a photo (from a medical school yearbook) that showed the future Governor wearing blackface next to a classmate in a Ku Klux Klan costume.

For months, both Hakeem Jeffries and Gregory Meeks refused to call for Cuomo’s ouster — despite many of their fellow New York City representatives doing the opposite. As Cuomo received his coronavirus vaccine at a Harlem church, former Congressman Charlie Rangel said, “When opposition starts piling up, you go to your family, you go to your friends because you know they will be with you.” In his hour of need, Andrew Cuomo found his family and friends, politically, in many of New York’s Black clergy and elected officials. Indeed, with each public survey, the majority of Black voters replied that the Governor should not resign.

In a last-ditch effort to buy time, Cuomo authorized State Attorney General Letitia “Tish” James to oversee an independent investigation into his conduct. The besieged Governor, increasingly desperate, attempted to influence the investigation by suggesting the Attorney General share investigation responsibilities with Janet DiFiore, a judge appointed by Cuomo and regarded as an ally of the Governor. James rejected this maneuver.

“Wait for the facts,” Andrew Cuomo insisted. “An opinion without facts is irresponsible.”

On August 3rd, in the form of the much-anticipated Attorney General’s report, the facts came.

The Attorney General’s report “not only found that Cuomo sexually harassed eleven women, but that a cadre of his top aides and associates engaged in unlawful retaliation against one of the women — retaliation that frightened others into maintaining their silence.” Several more troubling allegations, which were previously not disclosed to the public, were included in the report — most damningly that of “Trooper 1,” who testified that the Governor “alluded to her sex life” and “ran his hands over her body.”

“The Executive Chamber’s culture—one filled with fear and intimidation, while at the same time normalizing the Governor’s frequent flirtations and gender-based comments—contributed to the conditions that allowed the sexual harassment to occur and persist.” (Report of Investigations Into Allegations Of Sexual Harassment By Governor Andrew M. Cuomo)

The fallout was swift and intense. President Joe Biden said Cuomo should step down given the Governor faced certain impeachment. Cuomo loyalists throughout state government, holdouts who resisted the resignation calls of their colleagues for months, buckled under the weight of the Attorney General's damning expose. Polls released the following days showed more than sixty-percent of New Yorkers believed Cuomo should be impeached; and now, both the State Assembly and State Senate had the votes to forcibly remove the Governor.

After stalling for months, Andrew Cuomo had nobody to turn to, and no moves left.

On Tuesday, August 10th, 2021 — he resigned as Governor of New York.

“Saddam has been toppled.” — Micah Lasher

Miriam Pawel, a reporter who had known Mario and Andrew Cuomo for decades, summed up the latter’s failures, in the prose of the former, perfectly:

“Watching Andrew Cuomo’s final days reminded me of one of his father’s favorite parables, about the wasp and the frog (more commonly told about a scorpion, but Mario Cuomo always used a wasp). The wasp asks a frog for a ride across a river. The frog is leery, but the wasp points out that if he were to sting the frog, they would both drown. The frog accepts the logic. In the middle of the water, the wasp strikes.

As they are drowning, the wasp explains, ‘I couldn’t help it. It’s in my nature.’”

In The Wilderness

“Everything about Mr. Cuomo — his home, his legacy, his identity — is wrapped up in a governorship… Being governor, in other words, is his oxygen.” (The New York Times)

Having resigned in disgrace, one might have expected Andrew Cuomo to swiftly retreat from public life, not to be heard from again for months, perhaps years. And, while Cuomo maintained a low profile as fall crested into winter, all while watching his successor, former Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul (whom Cuomo intended to leave off his fourth-term ticket), push his new nemesis, Attorney General “Tish” James out of the Governor’s race — clearing the field of all serious opponents. Unable to “stomach” his new life — one of shame, lived on the political sidelines, and crucially, absent any of the power he desperately craved — Cuomo seriously weighed the prospect of a quickfire comeback against Hochul. With several polls showing the former Governor within striking distance of the newly-minted incumbent, Cuomo released multiple campaign-style television advertisements touting his record.

However, the few friends Andrew Cuomo had left, like New York State Party Chair Jay Jacobs, as well as the institutions, such as organized labor, that the former Governor routinely bent to his will — all publicly backed Kathy Hochul for a full term in an effort to dissuade the former’s potential comeback. Cuomo had gone from speaking daily with the President of the United States to tagging along with controversial has-been Rubén Diaz Sr (a Pentecostal Minister and former elected official known for a history of homophobic remarks). Persona non grata to the political class, Andrew Cuomo retreated to the environment he felt most comfortable: the Outer Borough Church Circuit, addressing Hispanic Clergy in the South Bronx on Saint Patrick’s Day, while railing against “cancel culture” at God’s Battalion of Prayer in East Flatbush. However, after months of speculation and several efforts to gradually rehabilitate his image, Cuomo declined to seek his former position. “Too soon,” his closest aide Melissa DeRosa wrote.

Would Andrew Cuomo, now at the mortal age of sixty-five, ever have a better opportunity?

One would have thought Cuomo — the eldest son of a three-term Governor, alumnus of the Clinton Administration, onetime New York State Attorney General, and thrice landslide victor of New York’s highest office — was a stranger to any degree of career adversity, let alone the political wilderness he now found himself amidst.

However, Andrew Cuomo was well-acquitted with such an aimless, restless existence — for Mario’s son had known the feeling intimately, two decades ago.

A few years removed from serving as Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Andrew Cuomo fancied himself as the Democrat best positioned to dethrone Republican Governor George Pataki — avenging the painful defeat of his father, eight years prior, in the process. However, State Comptroller Carl McCall, a favorite of New York’s Black establishment, stood between Cuomo and the Democratic nomination. Many close advisors, keenly aware that a campaign against McCall would stoke resentment among Black political leaders, tried to hold him back — to no avail.

“In early focus groups, recalled Richie Fife, a McCall adviser, ‘People would watch a tape of Andrew and would react negatively. One said, ‘He sounds like Mario, but there’s no heart.’”

Andrew Cuomo’s style, a take-no-prisoners brashness of always attacking and never relenting, was a particularly poor fit for New York in the wake of September 11th, when sensitivities loomed large, and political fodder, especially those invoking the attacks, were poorly received by an electorate still reeling. However, surrounded by reporters on his campaign bus, Cuomo could not hold himself back: he wasn’t buying the line that Governor Pataki had shown such strong leadership in the wake of the terrorist attacks — New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani was the real hero. “There was one leader for 9/11: it was Rudy Giuliani,” Cuomo declared. “If it defined George Pataki, it defined George Pataki as not being the leader. He stood behind the leader. He held the leader’s coat. He was a great assistant to the leader. But he was not a leader.” Instantly, Andrew Cuomo had introduced partisanship into a tragedy.

Overconfident, entitled, crass, and disorganized — Cuomo saw his once sizable lead (which peaked at twenty-three points), largely owed to the resonance of his father’s legacy, dwindle over the course of several, mistake-laden months. Despite raising close to ten million dollars, his insensitive comments not only halted his momentum — but killed it outright. To say he was consistently off-message would be charitable, because he had no message. The principal wanted to be both candidate and strategist, doing both poorly. Cuomo grew increasingly frustrated as he watched his polling numbers steadily decrease, the press stop taking him seriously, and the political establishment rallied to McCall’s side. His opponent’s allies called him “Andy” as though he were a petulant child unable to get his way. The moniker stuck. Cuomo’s closest and most powerful ally, the Clinton family, was conspicuously silent — until Hillary, then-New York State’s Junior Senator, marched down Eastern Parkway alongside McCall at the West Indian Day Parade in Brooklyn (Chuck Schumer, New York’s Senior Senator, also endorsed McCall). Beyond the political class, rank-and-file Democrats were now tuning into the campaign, and increasingly turning away from Cuomo.

The more voters learned about Andrew Cuomo, the less they liked him.

Confronted with the reality of imminent defeat, Andrew Cuomo, privately, agreed to withdraw and endorse Carl McCall on the eve of the Democratic Primary, provided his three conditions — First, a high-profile role in McCall’s fall campaign; Second, McCall to pledge his future support, specifically, an endorsement if Cuomo chose to run for Governor in 2006; Third, for McCall to state publicly that Cuomo’s withdrawal had been brokered by former President Bill Clinton — were met by his opponent. And, if McCall rebuffed said demands, Cuomo signaled an intention to deplete his remaining warchest (over three million dollars) bludgeoning the frontrunner over the final week, with the implicit threat that such an onslaught would irreparably damage the Democratic nominee ahead of his November faceoff with Pataki.

His bluff was called, no “conditions” were met, and Andrew Cuomo withdrew without a huff on the eve of the Democratic Primary (McCall was crushed by Pataki in the ensuing General Election).

“A soothing mood of unity was meant to drape the occasion, a goal somewhat hindered by the fact that Andrew’s rival wasn’t there. Charlie Rangel, the Harlem congressman, stood on one side of Andrew. On the other stood former President Clinton, coaxed into dignifying the occasion with his presence. “Today is a day you should be very, very proud of, Andrew,” the President declared to a hastily gathered crowd that included Kerry Kennedy, Andrew’s parents, and his sister Maria, all in the front row. This was the right decision, Clinton intoned, good for the party, and Andrew would live to fight another day. The only political career that was over, the former President joked, was his own.”

(The Contender, Michael Shnayerson)

Many observers were less kind. Jake Tapper said Cuomo’s “grating personality has sullied what could have been a promising campaign,” and called the withdrawal “a rare moment of grace” for someone who typically “[blares] his obnoxiousness for all to suffer.” In the minds of voters, Tapper added, “he seemed like an asshole. And sometimes a politician’s problems are truly that simple.” But Cuomo’s problems did not end with his embarrassing defeat.

The day after the primary, Kerry Kennedy demanded a divorce. Months later, they separated. As the tabloids printed several pieces detailing Kennedy’s extramarital affairs, the once-celebrated “Cuomolot” — the union of two political dynasties — was dead.

Andrew Cuomo was humiliated, personally and professionally.

Even back then, Cuomo never lacked campaign donors, journalist contacts, political consultants, and fixers. However, what he needed were friends — individuals, not dependent on a lucrative check or the teet of political power, who could save him from his worst instincts, both on the campaign trail and in his troubled marriage. Two decades later, when Andrew Cuomo, having battled back from the depths of irrelevance, found himself once again on the precipice of banishment, the same words — a leader insulated (of his own intention) by a sycophantically small circle, where those who stayed adopted the principal’s relentless ethos, oftentimes at the expense of all else — would be written about the shocking downfall of New York’s Governor, as though nothing had changed in twenty years.

He would only have himself to blame.

A perfect storm of luck and circumstance (and, to a lesser extent, greater discipline) would return Andrew Cuomo from the brink of irrelevance. Despite the catastrophe of the Gubernatorial bid, Mario’s son knew he had one more run (for a lower office) in him. Four years later, popular Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, dubbed the “Sheriff of Wall Street,” was tapped to lead the Democratic resurgence in New York State. As such, Spitzer, who went on to win (in historic landslides) both the Democratic Primary and General Election for Governor, vacated his Attorney General post, creating a coveted opening.

Enter “Andrew 2.0”

Once ominously referred to as “The Prince of Darkness,” Andrew Cuomo took strides to reshape his image — reigning in his behavior, rather than reforming it. Gone were the “freewheeling” press chats (which had led to his September 11th faux pas), replaced with an obsessive amount of control over all aspects of his “political surroundings.” Where some saw a redemptive arc, others felt an air of shallowness — that Cuomo’s contrition amounted to nothing more than a “blanket apology.”

Nonetheless, Cuomo steamrolled his weak competition — washed-up Mark Green and early-career Sean Patrick Maloney — winning all of New York’s sixty-two counties. Despite the presence of Charlie King, Cuomo’s former pick for Lieutenant Governor, in the race — the man who was once iced out by the Black political establishment had steadily improved his standing with a community integral to his future advancement; (King, set to serve as Cuomo’s campaign manager on his upcoming Mayoral campaign, dropped out before the Primary and endorsed the frontrunner).

Andrew Cuomo was not Governor (yet), but he had salvaged his political career.

However, in less than sixteen months, Governor Eliot Spitzer, once hailed as a contender for the White House, had resigned in disgrace — engulfed in a prostitution scandal. Lieutenant Governor David Paterson, the former State Senate Minority Leader from Harlem, would finish Spitzer’s term, becoming the first African-American Governor in New York State history.

While the Governor had always warily eyed the ambitious Attorney General — particularly after Cuomo’s office published a damaging report (“Troopergate”) exposing the Spitzer Administration’s police surveillance of then-State Senate majority leader Joseph Bruno's whereabouts — the former’s undoing was entirely borne of his own indiscretions.

Indeed, New York State political history frequently repeats itself.

Paterson, thrust into the state’s top position, proved ill-equipped to handle the job. Quickly, the former Harlem Senator saw his approval ratings plummet while New York’s fiscal outlook (as a result of the Great Recession) deteriorated. Amidst a generational opportunity (and a critical chance at a political reset), Paterson was tasked with selecting New York’s next United States Senator (upon Hillary Clinton’s confirmation as Secretary of State). Among the Governor’s rumored choices: Congress Members Nydia Velázquez, Jose Serrano, Carolyn Maloney, Kirsten Gillibrand, political heiress Caroline Kennedy, Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown, and… Andrew Cuomo. The early frontrunner, Kennedy (Cuomo’s former sister-in-law) abruptly withdrew at the eleventh hour following a series of less-than-inspiring public appearances. Ultimately, Paterson’s choice was narrowed between Cuomo, himself already eyeing the increasingly vulnerable incumbent Governor, and Gillibrand, the dark-horse favorite of Chuck Schumer. While choosing Andrew Cuomo to fill the vacated U.S. Senate seat would have immediately removed Paterson’s greatest threat to his upcoming re-election, the Governor passed on promoting his Attorney General, whose approval rating doubled the beleaguered Governor, and selected Gillibrand. Most consequentially, Paterson nabbed Gillibrand from a purple district in Upstate New York, potentially costing Democrats a seat in the upcoming midterm elections (it did), angering President Barack Obama.

But that was not the only gripe the President had with David Paterson.

In fact, the incumbent’s poor standing, combined with the prospect of former New York City Mayor Rudy Guliani running for Governor (as the Republican nominee), was cause for grave concern in the White House, who feared a bloodbath in New York with Paterson leading the Democratic ticket in the upcoming midterm elections.

“Mr. Obama’s political team and other party leaders have grown increasingly worried that the governor’s unpopularity could drag down Democratic members of Congress in New York, as well as the Democratic-controlled Legislature, in next fall’s election.” (The New York Times)

As David Paterson asserted his intention to remain in the race, Andrew Cuomo was already circling the wounded Governor. However, the Attorney General was cautious not to prematurely declare Paterson’s political fortunes dead on arrival — for months, as rumors of the incumbent’s demise echoed through the halls of power in Albany, Cuomo did not spend a dime on polling or consultant fees — preferring to wait out the situation from the shadows. His intentions, publicly, were to run for Governor if Paterson was forced out; whereas launching a primary challenge against New York’s first Black Governor would risk repeating the Carl McCall fiasco. In reality, Cuomo intended to run regardless, but moving too soon could risk exacerbating racial tensions; better to be patient, and wait for Paterson to implode, or his fickle allies to inevitably turn on him. Without fail, as the Attorney General lurked in the shadows, the Governor was dealt a devastating blow from the most celebrated politician in both the Black community, and the Democratic Party at large: “President Obama had sent a request to Mr. Paterson that he withdraw from the New York governor’s race, fearing that Mr. Paterson cannot recover from his dismal political standing, according to two senior administration officials and a New York Democratic operative with direct knowledge of the situation.”

“Mr. Cuomo effectively has the blessing of the nation’s first black president to run against New York’s first black governor.” (The New York Times)

Specifically, the White House named “popular” Attorney General Andrew Cuomo as their preferred Democratic standard bearer in New York State. While Paterson defied the wishes of the Obama Administration, even when said request was leaked to the press, the intervention of the first Black President gave cover for other Democratic interest groups to eschew the unpopular Paterson for the more palatable Cuomo, whose patience had paid off handsomely. The scandal-scarred Governor pushed forward regardless, but his campaign ended before it even began. David Paterson withdrew amidst several criminal probes (including from the Attorney General’s office) after The New York Times reported that his administration had intervened in a domestic violence case involving a longtime aide. With Paterson finished, Andrew Cuomo captured the Democratic nomination without the faintest hint of competition. The man whose life had imploded (publicly) less than eight years prior, who was too impatient and unwilling to wait his turn, had indeed been patient. While benefiting from a perfect storm of circumstance and luck, he nonetheless restrained his worst instincts, repaired his standing in the Black community, and coalesced the Democratic Party in New York State at a moment’s notice. In November, the threat of Rudy Guliani never materialized, and Andrew Cuomo easily won his first term as Governor, ushering in an eleven-year reign atop New York State government.

The rest is history.

One Last Chance

“Never let a crisis pass you by” – Andrew Cuomo

Today, Democrats in New York State are navigating their most pronounced political power vacuum since the early days of the millennium. Governor Kathy Hochul, two years removed from a lackluster six-point victory in the 2022 midterm elections, remains as unpopular as ever — perpetually in the crosshairs of presumptive future Republican nominee (Hudson Valley Congressman Mike Lawler), besieged daily by an ambitious member of her own party (Bronx Congressman Ritchie Torres), while her own Lieutenant Governor (Antonio Delgado) rushes to distances himself from her administration.

If Andrew Cuomo desires to return to the Governor’s Mansion, the well-documented struggles of his successor has cracked open the door to a political comeback. Nonetheless, Kathy Hochul — eighteen months away from her next re-election test, armed with an eight-figure warchest, at the helm of the state’s most powerful position, and, crucially, without the specter of criminal charges — is far from the most vulnerable executive in New York.

That honor, exclusively, belongs to New York City Mayor Eric Adams.

The charge: corruption.

Over the last several months, there seemed to be an FBI Raid, Indictment, or Resignation connected to either Eric Adams’ 2021 campaign or his Mayoral Administration — almost every week. In September alone, the NYPD Commissioner, Schools Chancellor, Deputy Mayor for Public Safety, and the City Hall’s Chief Counsel all resigned in a matter of weeks. In December, the mayor’s right-hand, Ingrid Lewis-Martin, resigned following an indictment on bribery charges; Mohamed Bahi, who worked in the mayor’s community affairs office, also resigned before being charged with witness tampering and destroying evidence; Jeffrey Maddrey, the NYPD’s highest-ranking uniformed officer, was suspended while his home was searched following a Police Lieutenant's allegation that Maddrey coerced her into having sex in exchange for overtime payments.

However, the extent of said unethical behavior was not solely confined to the Mayor’s cronies.

On September 25th, federal prosecutors unveiled a five-count indictment against Eric Adams, charging him with bribery, conspiracy, fraud, and soliciting illegal foreign campaign donations. Furthermore, Adams was recently denied public matching funds by New York City’s Campaign Finance Board, as the body “determined there is reason to believe the Adams campaign has engaged in conduct detrimental to the matching funds program, in violation of law.” Even before criminal charges were levied against the Mayor and his associates, Adams’ approval rating, amidst a lackadaisical first term in City Hall flush with rhetoric (but short on results), was already dreadfully low.

In February, Danielle Sassoon, the interim US attorney for the Southern District of New York, tendered her resignation following a recent order from the Department of Justice to drop corruption charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams. In an episode dubbed the “Thursday Afternoon Massacre,” five additional officials with the federal public integrity unit chose to quit rather than obey the DOJ’s directive. In her resignation letter, Sassoon alleged, “[Eric] Adams’s attorneys repeatedly urged what amounted to a quid pro quo, indicating that Adams would be in a position to assist with the Department’s enforcement priorities only if the indictment were dismissed.”

While Governor Kathy Hochul ultimately elected to not remove Eric Adams, an option she weighed following the resignations of four deputy mayors — Maria Torres-Springer, Meera Joshi, Anne Williams-Isom and Chauncey Parker — the latest chapter in the Mayor’s corruption saga marked the official end of his already slim re-election prospects.

However, for several months following the indictment, many across the political class were reluctant to write off a scandal-scarred Mayor — in part, a reflection of credible questions about the coalition-building potential of those who are challenging the vulnerable incumbent.

While Brad Lander is poised to perform well across the vote-rich, civically-engaged neighborhoods of Manhattan and Brooklyn, if the former Park Slope Council Member stumbles in the working-class Black, Hispanic, and Asian enclaves throughout the outer boroughs — his professional-class prowess may not matter. While Lander can credibly lead on managerial competency, demonstrating an understanding of government’s nuts and bolts, the former Chair of the Progressive Caucus will have greater difficulty assuaging fears of crime and disorder (issues that, if metastasized, can fray his fragile coalition). Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani maintains a fervent base of support across the millennial-heavy, Bernie Sanders-loving, gentrifying neighborhoods that stretch from Astoria to Sunset Park, with the potential to further activate and mobilize the city’s growing South Asian and Muslim population. In three months, Mamdani has amassed an impressive fundraising haul, both in size and scope, earning praise from The New York Times as the progressive candidate with “the most momentum.” However, the enduring question for Mamdani’s path-to-victory will be whether — in a Democratic Primary, where a majority of votes come from either homeowners, or those whose class composition can be described as upper middle-class and beyond — the democratic socialist can fuse a coalition capable of eventually reaching fifty-percent in a ranked-choice-runoff, particularly if a tidal wave of outside spending arrives from Pro-Israel groups and the Real Estate lobby. Scott Stringer is attempting a comeback of his own, after the onetime frontrunner’s campaign crashed and burned four years ago following two allegations of sexual misconduct. Already, Stringer has qualified for matching funds with a concentrated donor base that spans both sides of Central Park (in addition to the Chinese enclaves of Flushing and Bensonhurst) while consistently placing well across a handful of early polls. However, the question remains whether the former Comptroller can maintain (and increase) his standing, despite a fraction of the institutional support he enjoyed last cycle.

State Senators Zellnor Myrie and Jessica Ramos would make solid, one-on-one candidates against either Eric Adams or Andrew Cuomo — their challenge is making it that far. Following a lackluster fundraising haul in her first month ($52,513), Ramos fired her campaign manager and fundraising director, among others — an auspicious start to any Mayoral campaign, particularly given the balance sheet of the Jackson Heights-native showed little improvement as the January fundraising deadline came and went.

While Zellnor Myrie’s fiscal standing remains in better shape, his polling — consistently stuck in the low single-digits — does not. Myrie has defined himself, in part, as the YIMBY (“Yes In My Backyard”) candidate, a constituency whose chief issue is increasing New York City’s housing supply (quickly). However, the political power of the YIMBY coalition, at this time, is largely confined to the political class, and does not represent a pronounced constituency within the electorate itself. In many respects, the crosscurrents of Myrie’s own State Senate District reflect his loosely defined political base: Park Slope and Windsor Terrace are Brad Lander’s two strongest neighborhoods; Prospect Heights had the highest share of Working Families Party ballots this November; and majority-Black Crown Heights delivered over fifty-percent of the vote to Eric Adams four years ago.

Crucially, even as Black voters defect from the Mayor — thus far, they are backing Andrew Cuomo, not Zellnor Myrie.

The current field of competition, while intriguing, is beatable. No Mayor since Abe Beame, in the throes of a fiscal crisis which brought the city to the brink, has faced bleaker re-election prospects than Eric Adams. The various challengers, each with their respective weaknesses, have not coalesced, and thus will be reliant upon a coordinated ranked-choice-voting strategy to overcome their more well-known opponents. Cuomo, who knows he has one last chance at a comeback, surely realizes this moment is his best opportunity.

Andrew Cuomo’s entrance will deal a devastating, fatal blow to Eric Adams on several fronts. Despite the incumbent’s precarious overall standing, Adams has maintained some semblance of goodwill with New York City’s Black population, roughly thirty-percent of the Democratic Primary electorate, and the consistent core of his electoral base. After winning seventy-five percent of the vote in working-class Brooklyn neighborhoods like East Flatbush and East New York, seventy-percent in both working-poor Brownsville and middle-class Rochdale, and sixty-five percent in majority-homeowning Canarsie, Wakefield, and Springfield Gardens — Adams appeared on pace to once again reach respectable margins across New York City’s Black neighborhoods.

However, the Mayor’s indictment has fueled his gambit to curry favor with Donald Trump, a move many observers have cited as the embattled executive appealing for a pardon. In one week alone, Eric Adams met with the President in Florida, dined with top New York Republicans, stated he would no longer criticize Trump publicly, appeared on the Tucker Carlson Show, and cancelled (last-minute) his appearances in Harlem and Fort Greene honoring the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in favor of attending the Inauguration. In response to the Mayor’s recent flirtations with the GOP, the Reverend Al Sharpton, a steadfast ally, replied, “To say you’re not going to raise your eyebrows would be dishonest. I think that this will cause a lot of us to say, what is this all about?” Most importantly, New York City’s Black neighborhoods are the most populated, pro-Democrat, anti-Trump constituencies in the Unites States. Amidst more rumors of resignation, reports that the Justice Department may drop their charges against Adams, late-night meetings with labor leaders, and an undisclosed illness which kept the Mayor sidelined, NY1 anchor Errol Louis asked whether, “New York City Even Have a Mayor Anymore?”

In 2002, Andrew Cuomo had severely misjudged his standing in the Black community, to the point where “virtually no black leader publicly endorsed him.” Now, it appears the same could be said about Eric Adams, who is trailing Cuomo, significantly, among his core constituency. When Adams first encountered the specter of future legal trouble, Cuomo and his allies were resolute that the former Governor would only run for Mayor if the incumbent was forced out, careful to not pre-emptively risk alienating Black leaders (for the record, the author never believed that assertion). As was the case with David Paterson, waiting on the sidelines (for now) has paid dividends for Cuomo, as Adams is content to implode all on his own. After struggling mightily to win the trust of the Black political establishment early in his career, Andrew Cuomo became one of the more popular white politicians among New York City’s Black electorate (a list that also includes Bill de Blasio and John Lindsay).

The muffled cries of New York City’s electorate are multi-fold: a swift return to non-corrupt normalcy that allows government to function adequately, absent investigations and scandal; and assurances that their growing anxieties concerning disorder and random violence, catalyzed by the chilling video of Debrina Kawam’s death aboard the F train, will be recognized and addressed. The latter fears, growing among New York City’s multiracial working-class since the pandemic, have been an achilles heel for progressives, particularly in the outer boroughs. And, while a noted strength of Eric Adams (the Mayor made tackling crime his signature issue four years ago), the corruption that has engulfed his administration will leave the incumbent persona non grata among the high turnout, civically-engaged white collar professionals in Manhattan and Brooklyn. However, crippling post-pandemic inflation, the relentless economic populist message of Zohran Mamdani, and collective progressive support for universal childcare, has shifted the proverbial zeitgeist to encompass costs of living concerns as well.

With respect to the rules of engagement, Andrew Cuomo would be most comfortable playing on the field of public safety against his progressive rivals. On the contrary, responding to the economic plight of voters could prove troublesome for the man who shuttered hospitals in working-class neighborhoods, imposed cost-cutting measures that spurred a transit worker shortage, and allied with real estate developers at every opportunity. However, it will be here, in the proverbial middle ground — regaining public trust in New York City’s governing institutions — where Andrew Cuomo wins or loses his comeback campaign for Mayor. For some, the notion of the former Governor restoring order at City Hall will be welcomed with open arms, particularly in the second era of Donald Trump. For others, replacing one disgraced and scandal-scarred executive with another would represent not only a missed opportunity, but a grave failure.

Radioactive to many progressives, a plight he shares with the incumbent Mayor, Andrew Cuomo has a higher ceiling than Adams’ with respect to the remainder of the electorate. The dwindling number of ethnic whites — across Staten Island, Southern Brooklyn, Northeast Queens and the East Bronx — remain low-hanging fruit for Cuomo, and will be the former Governor’s for the taking. The city’s Hispanic population, approximately one-fifth of the primary electorate, instrumental in helping Eric Adams cross the fifty-percent threshold (the former Brooklyn Borough President dominated with all Latino nationalities and economic classes), have increasingly soured on the Mayor (and the Democratic Party). Could Andrew Cuomo, a known commodity who earned between eighty and ninety percent of the vote in majority-Latino neighborhoods against Nixon, win a plurality of this electorate, one that appears genuinely up for grabs? Much of the same could be said for the politically moderate, predominantly working-class East Asian electorate (Zohran Mamdani is favored to carry South Asian precincts), who (upon Andrew Yang’s elimination) tepidly split their support between ranking the aforementioned Adams, Kathryn Garcia, or neither (ballot exhaustion was highest [over thirty-percent] in Flushing, Sunset Park East, Bensonhurst, and Gravesend) four years ago. Already less than ten-percent of the primary electorate, the alienation of New York City’s East Asians from the broader Democratic coalition has been one of the preeminent political developments of the last several years. Their plight — one of public safety and preserving the specialized high school entrance exam — is not atypical for those who live at the ends of subway lines and harbor dreams of comfortable middle-class life, but cannot be defined solely along ideological or ethnic lines either, evidenced by the respective resonance of: Susan Zhuang, who infamously (allegedly) bit a police officer during a protest against a homeless shelter in Bensonhurst; Bill Colton, a staunch ally (and mentor) of the former, sole Democratic remnant of consecutive red waves across Southern Brooklyn, and steward of one of the few remaining political clubhouses that maintains genuine influence over local elections; and Ron Kim, a populist champion of homecare workers, who has habitually fended off right-leaning challenges from Democrats and Republicans. Absent a handful of local electeds (not to mention Rep. Grace Meng), few in the Democratic Party have adequately gained the trust of this growing cohort — with the upcoming Mayoral race appearing to be no different. Lastly, the votes of Hasidim and Orthodox Jews — throughout Borough Park, Midwood, South Williamsburg, and Far Rockaway — could be a boon to Cuomo as well. Frequent readers of this newsletter will recall that, despite the outsized coverage bestowed on the blessing of this religious cohort, the Orthodox and Hasidim deliver relatively few votes in a Democratic Primary (if all threads line up, a margin of ten-thousand votes can be gained), particularly if the uniformity of their backing (rabbis from separate sects endorsing different candidates) is watered down. However, when the margin-of-victory is seven-thousand votes (as was the case last cycle), every ballot counts, and Cuomo, already aggressively courting the most Pro-Israel segments of the electorate, will have an excellent opportunity to undercut the vulnerable Adams, and preemptively bank thousands of votes over his closest rivals. Already, Cuomo’s allies, including two former aides to President Trump have taken steps to prepare a Super PAC to boost his bid, according to emails obtained by The New York Times.

Undoubtedly, the former Governor’s (many) detractors will feverishly highlight the series of scandals that emanated from Cuomo’s own administration — not to mention his tepid connection to New York City over the past two decades. However, whether such attacks can make an impact beyond the professional class, who soured on the former Governor long before he stepped down, remains to be seen. Even before the sexual harassment allegations came to light, Andrew Cuomo was hemorrhaging popularity across Brownstone Brooklyn and Manhattan’s predominantly white, upper-middle class enclaves — neighborhoods where the incumbent Governor lost out to actress Cynthia Nixon in the 2018 Democratic Primary.

That aforementioned Primary, now over six years ago, marked the last period where New York City’s broad left-of-center coalition — a political confluence of the liberal reformer, the professional managerial class progressive, and the millennial leftist — remained united. Such a wave could not imperil the incumbent Governor, but it nearly took out his hand-picked Lieutenant Governor, and ultimately ousted half-a-dozen conservative State Senators, replaced by younger, more progressive members. Since then, these factions have kept their distance, most consequently during the previous Mayoral Primary, where good-government technocrats backed Kathryn Garcia while the ideological left rallied behind Maya Wiley — a lack of consolidation that many blame for the election of Eric Adams. Now, with another frontrunner deeply rooted in the outer boroughs, and several progressive challengers lumped together in the single digits, persistent anxiety remains across the spectrum of left politics that history could repeat itself.

Amongst this civically-engaged cohort, there is no love lost for Andrew Cuomo. But, can such a heterogeneous coalition set aside their grievances and come together in a shotgun-marriage to stop the former Governor?

And, even if they do, will their efforts be enough?

Crucially, those past victories were cemented along the brownstone blocks of Park Slope and Prospect Heights, the doorman buildings of the Upper West Side and Riverdale, and across the gentrifying precincts of Astoria and Williamsburg. Whereas the working-class and low-income neighborhoods of Corona, Brownsville, Cypress Hills, and Inwood stood by their incumbents — whom were decried as “Trump Democrats” in the more affluent parts of the district. Now, as many of those neighborhoods shift to the political right, will liberal Democrats once again prevail in spite of the multiracial, working-class?

Indeed, since the sexual harassment and nursing home scandals burst into view, Andrew Cuomo has not faced the voters. And, when he does in the coming months, the former Governor’s performance will be instructive of the seismic cultural divide — the white-collar, ideological, college-educated class of the urban core versus the relational, working-class of the outer boroughs — within New York City’s electorate, as well as the Democratic Party at large.

The former may be tempted to discount the electoral prospects of Andrew Cuomo. However, such a premature prognostication would come at the expense of the latter.

There will be thousands of Democratic voters, particularly the Black and Hispanic working-class lauded by liberal elites as the Party’s political base, who cast their ballots for the former Governor who resigned in disgrace — not because the sexual harassment and nursing home allegations do not register in their political calculus, but rather, because in a field of unknowns, Andrew Cuomo is known. With worsening economic conditions, far beyond the control of individual actors, making life more difficult for the low-income, working-poor, and middle-class across the five boroughs — many will look to a trusted, familiar face to restore order.

Political operatives across New York City, particularly those who desire for Andrew Cuomo to forever abscond from public life, know most of this. With Eric Adams imploding, Jessica Ramos and Zellnor Myrie struggling to breakout, and Zohran Mamdani and Brad Lander too left-leaning for the pro-business, moderate power brokers that routinely control political power in Black and Latino neighborhoods, Attorney General “Tish” James and labor leaders have spearheading efforts to recruit City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams for an eleventh-hour entrance, as perhaps the only candidate who can go toe-to-toe with Cuomo across the Black electorate.

Undoubtedly, Cuomo’s opponents will compare him to the early polling leaders of past campaigns, who ultimately faded down the stretch, such as Andrew Yang (who, one year removed from a Presidential bid, ultimately finished in fourth place) and Eliot Spitzer (another former Governor who ran for Comptroller, before losing narrowly to Scott Stringer). However, Andrew Cuomo is not Kamala Harris, and a shorter campaign — minimizing the exposure window of attacks — will be advantageous. The Democratic Primary electorate in New York City knows Cuomo (for better or worse). Given Cuomo’s aversion to retail politics, the former Governor will likely attempt a “Rose Garden” campaign from the shadows, intent to keep unscripted moments and press access “to a minimum” — at least, until his opponents give him reason to emerge.

With The New York Times Editorial Board, the city’s preeminent liberal institution, sidelined from political endorsements, the right-leaning New York Post will continue to shape the local media ecosystem unabated (and with it, the landscape of the Mayor’s race). While The Post may not be as deferential to Andrew Cuomo, particularly with respect to the Governor’s hand in undercounting nursing home deaths during the pandemic, as they were to Eric Adams four years ago, the right-wing tabloid has little incentive to go nuclear on the proverbial frontrunner, in lieu of attacking his more-progressive rivals.

Can Andrew Cuomo, with fewer institutional advantages than he has enjoyed in over twenty years, hold onto his considerable lead for the next four months, against a collective, chaotic onslaught — publicly and behind-the-scenes — from his opponents?

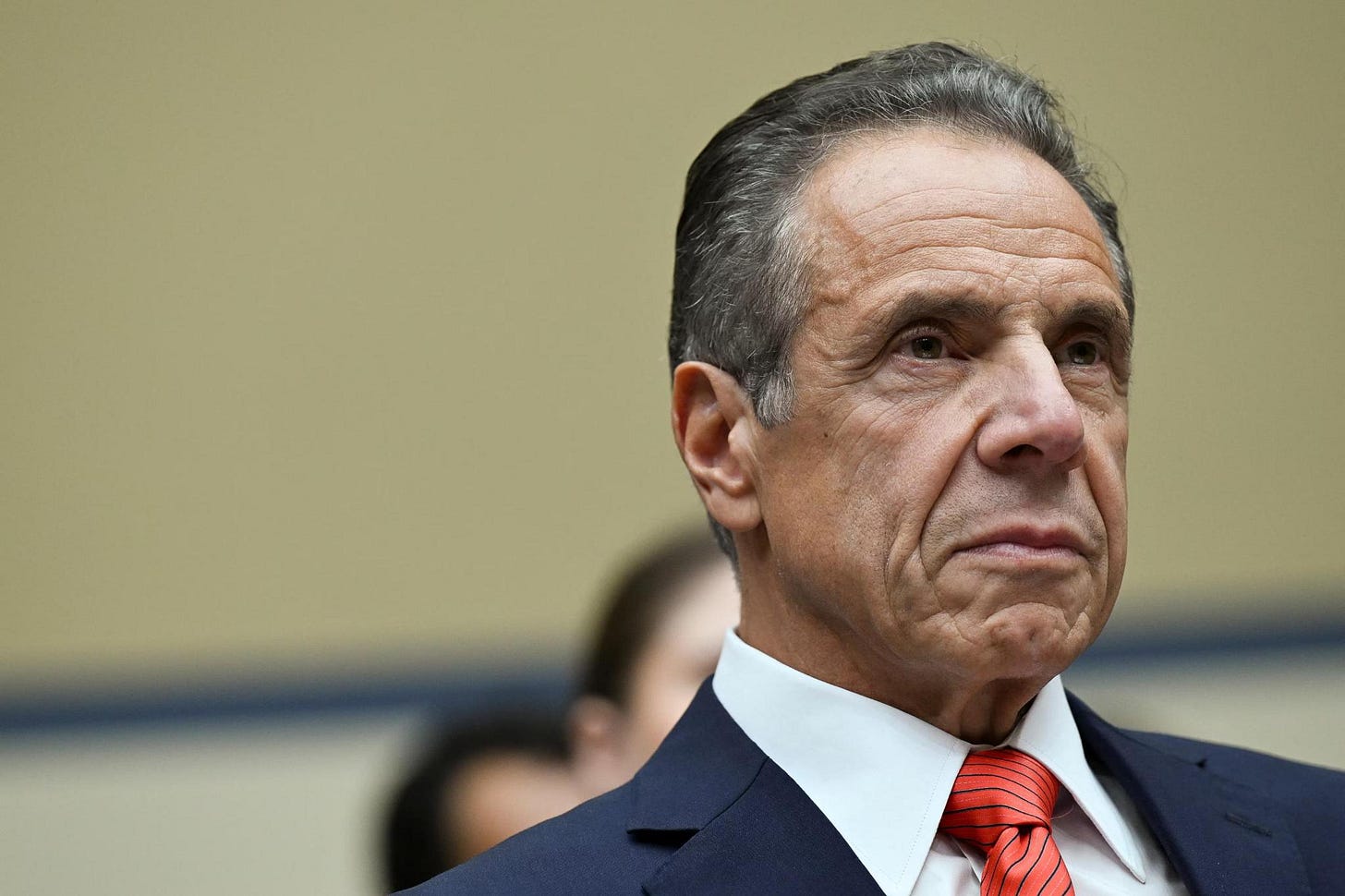

The Andrew Cuomo of today looks different than the man seen delivering pandemic addresses to the nation less than five years ago. Not photographed regularly for the past two years, Cuomo looks every bit of sixty-seven years old. His sturdy face, after three years in the proverbial wilderness, appears worn with wrinkles and lines; while the former Governor’s hair, trimmed short, shows more white and grey, while thinning out noticeably in the back. On the (shadow) campaign trail — in Central Brooklyn, East Harlem, and the Rockaway Peninsula — his cadence and timing are not as effortless as his pandemic apex, but the underlying connection with the audience remains. Indeed, much had changed since Andrew Cuomo, abandoned by the entire Democratic Establishment, announced his departure — whisked away on a helicopter, only heard from sporadically since. Facing inevitable impeachment and removal, his resignation had an air of finality, a bully forced to concede and surrender. His political obituary was written, once and for all, and his countless rivals, accumulated en masse over the years, collectively rejoiced. Not only was a political dynasty dead, but Andrew had besmirched his father’s legacy, failing to complete his third term as Governor, or win a record-breaking fourth. A black mark that would haunt the first line of his obituary. For a man who craves power to no end, there was no greater humiliation.

For months, Andrew Cuomo has played the proverbial game of “will he, or won’t he?”

Many considered the notion that the former Governor — used to ruling New York State with an iron fist — would subject himself to being Mayor of New York City (a thankless endeavor that has proven, time and time again, to be a career-killer), almost inconceivable; given the move would be, in many respects, a step-down in power from his old position. However, when one considers Cuomo’s personal history and arc — specifically, how his sense of self is intimately tied to his ability to wield political power — the answer becomes rather clear.

Andrew Cuomo watched his father, in a moment dubbed “Hamlet on the Hudson,” insist on completing an overdue state budget at the expense of running for President — only to shockingly lose re-election two years later, which brought an abrupt end to Mario’s decorated political career. Instead, it was another Governor, Bill Clinton, who stepped into the Democratic Party’s vacuum, creating a political dynasty in the process. Now, the son who perceived his father’s hesitation as weakness (indeed, Andrew Cuomo made a point of delivering on-time state budgets), has a golden opportunity to not only resurrect his career and redeem the family name, but exact revenge on the politicians and institutions who so gleefully cheered his demise.

“He wins, and the past is forgotten, or at least eclipsed.”

For Andrew Cuomo, nothing else matters.

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

I hope he wins, and de Blasio gets elected governor, and tortures him for four years.

Cuomo has more baggage than Louis Vuitton on Fifth Avenue. Can we Democrats finally turn the page on the political dynasties of the 1980s and 90s and get something new going on here? NYC needs to stop recycling and get to the top of the heap of defending next generation of liberal leadership.