The AOC—Trump Voter

As Donald Trump made inroads across New York City's multiracial working-class, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez outperformed Democrats up-and-down the ballot.

In the fall of 1989, ten days before Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was born, The New York Times profiled three families struggling to make ends meet, in a piece titled, “Working-Class Families Losing Middle-Class Dreams.”

“These are members of an all but invisible class: one out of every four New York families, who earn between $28,000 and $35,000 ($58–73K in 2020 USD). They hold secure, often blue-collar, jobs – subway motormen, truck drivers, firefighters, factory workers. But they cannot live the middle-class life that seemed within their reach a generation ago.”

For the article, Journalist Susan Chira spoke to Gilbert and Debra Matthews of Soundview, The Bronx and Harry Biolsi of Astoria, Queens — two, nonetheless distinct communities linked by their status as outer borough, working-class neighborhoods. Their testimony bears witness to New York’s best; [about Mr. and Mrs. Matthews] “New York City helped them by providing a relatively low-rent Mitchell-Lama apartment. The apartment towers rise around a pleasant grass courtyard, filled with trees, benches and children running in the twilight.”; and worst; ‘’I still walk the children to school,' Mrs. Biolsi said. 'They're not allowed outside alone.’'' Their anxieties about the precarious life of a New York City family; “Mr. Matthews does not see how he can afford to put his children through college. His oldest is 13; the youngest is 3. 'I think I'm making too much for them to get aid… Maybe they should think about [military] service,' he said’’; rings true three decades later; “In Astoria, his mother's friends all have their children moving back in with them. ‘The American dream of owning a home – in the city, it's dead,' [Biolsi] said. 'It might not be dead if you move to Montana, but you have to worry about jobs.’’

In describing the lives — white, black, and brown — of those who live in neighborhoods like Parkchester, Castle Hill, Throggs Neck, Corona, and Jackson Heights, Chira wrote, “most working-class New Yorkers, even if they sometimes dream of getting out, choose to stay. Despite the urban ills they live with every day, many say they are afraid to gamble what security they have and leave for other cities where prices are lower and life might be easier. Ties to family and friends hold them fast; and most find a corner of New York to savor.”

Three months later, David Dinkins, New York City’s first Black Mayor, was inaugurated at City Hall. With the ambitious hope of healing the racial, ethnic and class tension that had overwhelmed the city in the latter half of the 1980’s, Dinkins spoke of New York City not as the proverbial melting pot, but rather a “Gorgeous Mosaic — of race and religious faith, of national origin and sexual orientation – of individuals whose families arrived yesterday and generations ago, coming through Ellis Island, or Kennedy Airport, or on Greyhound buses bound for the Port Authority.” In many respects, Dinkins was describing the neighborhoods of what-is-now New York’s Fourteenth Congressional District, not only back then — but today as well.

Thirty-five years later, while much has changed across the Bronx and Queens neighborhoods anchoring the many iterations of this district — the ethos which unites the three-quarters of a million people who call it home, has not.

However, it was here — where the lines are blurred between working-class and working-poor; where dreams of middle-class life, despite an increasingly unforgiving city, continue to burn bright; where many of New York City’s most recent arrivals, be they college-graduates from out-of-town, soon to be Nuyoricans from the Island of Enchantment, or immigrants from Latin America (some with their documents, some without) — that, when compared with Presidential Election results just four years prior, Democrats saw some of their greatest losses this November.

In fact, no Congressional District in the entire country — save for the majority-Asian 6th Congressional District in Queens (0.1% greater) — swung so dramatically to the right as New York’s 14th.

Yet, as Donald Trump made inroads across New York City’s multiracial, working-class — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a progressive firebrand hailed by some as the “heir” to the Bernie Sanders movement and routine target of conservative media (and “establishment” Democrats alike), not only maintained her considerable support in a district as diverse as any in the United States, but outperformed Democrats up-and-down the ballot.

In fact, several precincts in heavily-Latino enclaves across Jackson Heights, East Elmhurst, and Corona delivered majorities to both Trump and Ocasio-Cortez. This phenomena, injected into the post-election zeitgeist by Ocasio-Cortez through a series of viral Instagram stories, captured national attention — quickly sparking debates within the ecosystem of Democratic Party media about economic populism, Gaza, and anti-establishment authenticity. Thus, the forthcoming analysis hopes to not only detail the extent of said ticket-splitting, but provide worthwhile insight into where the proverbial “AOC-Trump voters” were concentrated.

Overall, Ocasio-Cortez outperformed Harris by greater than six-points across her district — an impressive, above-average metric when compared with other Democratic incumbents in New York City, and across the country. However, solely relying upon a topline average to capture the countless nuances pulsing through the mosaic of New York’s 14th Congressional District would be a mistake. Thus, before sifting through the data, it is important to foreground the dozens of communities throughout Ocasio-Cortez’s district.

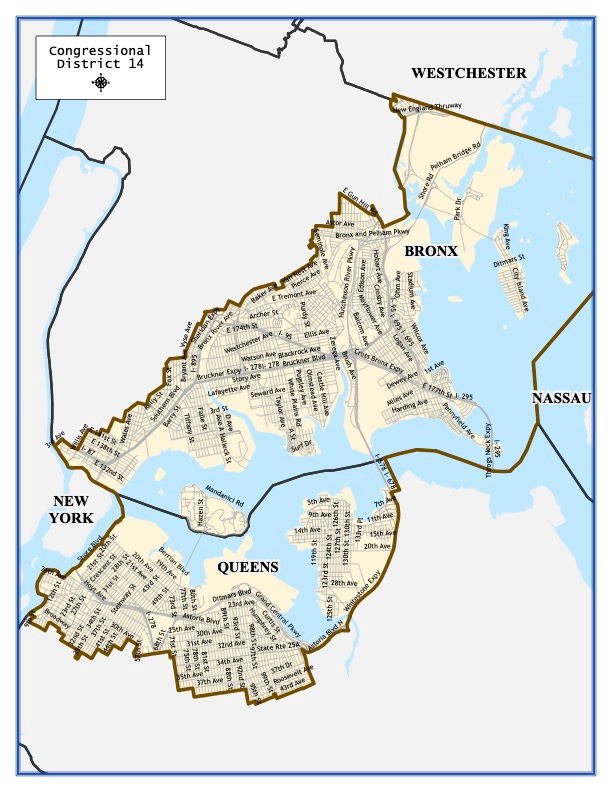

Bisected by the East River, the 14th District is split between New York City’s most working-class boroughs: the Bronx and Queens. While constituting a “Hispanic-opportunity” seat (~49%), protected by the Voting Rights Act, the district has double-digit percentages of Whites, Blacks, and Asians. The Hispanic population, while plurality Puerto Rican, remains exceptionally diverse, reflective of the city itself — with a growing Dominican base in the Bronx, and a considerable South American presence in the Queens neighborhoods of Jackson Heights and Corona. Here, there remains a genuinely remarkable mix between immigrants from outside the United States (approximately 40%), and those who have lived in New York State for their entire lives (almost 50%). While majority-Catholic, owed to the aforementioned Puerto Rican population, thousands of Latinos throughout the district — particularly in the Bronx — are Evangelical Christians. In addition to pockets of Greek Orthodox (Astoria-Ditmars), Buddhists and Hindus (Jackson Heights), the 14th District has the largest Muslim population of any Congressional District in New York City.

In New York’s 14th, English is a second language — if not a third, or a fourth.

Spanish, in a district where nearly half of all residents identify as Latino, remains the dominant dialectic — nowhere moreso than throughout the working-class Bronx neighborhoods along the local, Parkchester-bound, #6 train and the immigrant Queens communities of Jackson Heights and Corona within walking distance of the #7 train. The latter neighborhood of North Corona is home to the largest concentration of Spanish-Speakers in New York City — with some blocks exceeding ninety-one-percent of all residents (according to the U.S. Census). On the Queens peninsula of College Point, almost one-fifth of residents speak Chinese. In the industrial neighborhood of Westchester Square, and along the residential blocks above Northern Boulevard (either in Jackson Heights or East Elmhurst — depending on whom you talk to), approximately one-quarter of people speak Bengali. While English reigns in Astoria, and the upper-middle class, East Bronx enclaves within striking distance of the Long Island Sound, one can still hear Greek and Italian on many of these quiet streets — complete with paved driveways and impressive brick homes.

Nearly one-fifth of residents live in poverty. More than forty-percent of households earn less than fifty-thousand dollars per year. As such, almost three-quarters of residents remain renters — perhaps indefinitely — as the housing market ruthlessly punishes the outer-borough working-class, pushing more families to the brink with each passing day. Those lucky enough to remain anchored to their neighborhood via a rent-stabilized or subsidized apartment, may harbor dreams of one day leaving the city — in many cases, the only place known since birth — in search of greener, cleaner pastures and the ever-elusive suburban aspiration revered by the lower-middle class, but ultimately lack the modest means to do so. Indeed, only one in four who call the 14th District home have a college-degree. Here, amongst many neighborhoods considered “transit deserts,” owning a car in itself is a class-demarcator.

Of all the Congressional Districts in the United States, New York’s 14th ranks among the highest with respect to occupation in food service, healthcare, and transportation. For some, such employment — as a unionized transportation worker, for instance — remains a path to the aforementioned middle-class dream. Here, only the most fortunate (with enough savings or credit) can try their hand at opening a small business. For many, particularly those who earn close to the minimum wage (or are paid less, in cash off the books), their work is mired in the proverbial hamster-wheel where the lines blur between working-poor and working-class.

Barely enough money to reside in New York City. Not enough money to live in New York City.

Yet, when life in New York ground to a halt at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, these workers continued to serve the city without fail; perhaps at a more furious pace than ever before, even while experiencing loss as disproportionately as it was devastating. Their reward? As New York City rebounded from the depths of the pandemic, everything — housing, childcare, food — became more expensive, and nowhere was this pain felt more acutely than across the working-class neighborhoods of the outer boroughs.

On November 5th, that hurt was felt — by Democrats naive to its depth — at the ballot box.

However, the story of the 14th District is not one of statistics, but of Neighborhoods; and how, on June 26th, 2018, those neighborhoods, against long odds, chose one of their own — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — to represent them in Congress. Understanding the significance of the 2024 Election results, begins and ends with how the two are intertwined.

That story begins on the streets of “The South Bronx” — long the epicenter of New York’s Puerto Rican population. In search of manufacturing jobs, Puerto Rican migrants arrived in the South Bronx en masse following the second World War. Instead of opportunity, they were greeted with hardship: industries which had sustained the city’s working-class for generations were precipitously declining, migrating to the southwest; bills for the municipality’s generous social safety net were coming due, right as the middle-class tax base was fleeing for the rapidly-growing suburbs — via highways (like the Bruckner Expressway) paved over outer borough neighborhoods, already teetering on the brink of urban decay. As rampant landlord arson burned the borough in what was later described as the “Decade of Fire,” the South Bronx became shorthand for urban blight, embodied by President Jimmy Carter’s visit to Charlotte Street in 1977. While the South Bronx (depending on whom you speak to, the borders change: 149th Street on down, below Crotona Park, south of the Cross Bronx Expressway) was not the only working-class neighborhood to suffer under the austerity and increased crime that plagued pockets of the five boroughs from the mid-70’s through the late 90’s (Washington Heights, Brownsville, Bushwick, and the Lower East Side come to mind), it would not be an understatement to say that, in totality, the South Bronx bore as much — if not far more — than any neighborhood in New York City. This was the world that Ocasio-Cortez’s mother, a Puerto Rican-native who did not speak English upon moving to the United States, entered into when she joined her husband, a born and bred Bronxite, in a seventeen-story apartment house on Brook Avenue.

However, the South Bronx of today, particularly the stretch encompassed by the 14th District, does not resemble the images conjured up by the neighborhood’s oft-cited past. Like many New York City neighborhoods, the South Bronx is filled with crosscurrents and contradictions — large public housing developments across the street from luxury condominiums (the neighborhood is beginning to gentrify), with rent-stabilized tenements and newer, income-targeted units interspersed in-between. St. Mary’s Park, one block from the Brook Avenue apartment once shared by her parents, hosted Bernie Sanders on a cool, March evening in 2016 in advance of New York’s Democratic Primary for President — where Ocasio-Cortez, then twenty-six, was in attendance as one of the campaign’s Bronx organizers. Eight years later, Ocasio-Cortez would not only headline her own rally with Sanders (and fellow-Squad member, Jamaal Bowman) at St. Mary’s, she would be elected the neighborhood’s new representative (owed to decennial redistricting). When President Joe Biden was inaugurated, Ocasio-Cortez was not in Washington D.C. for the festivities; rather, she was in the South Bronx, specifically, the low-income peninsula split between industry and pre-war apartment houses known as Hunts Point, on a picket line with Teamsters Local 202 — despite the fact that, at the time, the neighborhood was outside of her Congressional District. Ocasio-Cortez’s appearance in support of a wage increase for workers at the Hunts Point Market, which “provides more than 60% of the produce for New York City,” increased media coverage of the strike, while galvanizing other elected officials to do the same. In less than one week, the strike was settled, as raises totaled $1.85/hour over three years, with 97% of striking employees voting in favor of the deal.

Following along the #6 train (as well as the Bruckner Expressway), the 14th District continues to stretch east: through the slowly-gentrifying Mott Haven, past the industrial-zoned Port Morris, by the charming Longwood historic-district, while reaching north along Sheridan Boulevard to include a piece of West Farms — a handful of blocks south of the Bronx Zoo, where over ninety-five percent of people rent their apartments, with the highest rate of poverty and lowest of high school graduation, of any neighborhood, in all of New York City. On the other side of the Bronx River, the class-composition of the 14th District changes — albeit gradually. While Castle Hill and Soundview are home to many public housing developments, their place on the horizon is marked by several, middle-income Mitchell Llama apartments — in addition to modest, multi-family homes which line the neighborhood’s side streets. On the middle-class peninsula of Clason Point, colloquially referred to as “Little Puerto Rico,” one can find waterfront condominiums, townhouses, multiple homeowner’s associations, and one of only two NYC Ferry stops in all of the Bronx.

Farther west, one will find the planned-community of Parkchester, with one hundred and seventy-one red-brick buildings adorned with terracotta sculptures which dot the East Bronx skyline for miles. Once, “whites only”, Parkchester stands today as one of the most integrated and diverse housing developments in the United States – one that has anchored the lives of the borough’s working-class for decades. It was here where Ocasio-Cortez’s parents, Blanca and Sergio, chose to raise their neighborhood’s future Congresswoman. Perhaps most importantly, Parkchester was considered a safer alternative than their previous residences in the South Bronx. With ample green spaces between the apartment houses, in addition to a self-contained shopping district — Parkchester offered valuable amenities, at a time when said offerings were few and far between for working families in the Bronx. Complete with many commercial spaces along its cloverleaf roads (Metropolitan Avenue & Unionport Road) and countless side streets, Parkchester remained as good a place as any to open a small-business — which Sergio did with his architecture firm, Kirschenbaum Ocasio-Roman.

However, the issue of school quality in the neighborhood, or lack thereof, has been repeatedly cited by Ocasio-Cortez as the driver of her family’s move north, at the age of five, to the upper Westchester suburb of Yorktown Heights. At the time, Parkchester was split between two separate Bronx school districts. Had Ocasio-Cortez remained in Parkchester, she would have been relegated to the 12th School District, which stretched west to include the impoverished neighborhoods of Tremont, Morrisania, West Farms, and Hunts Point — as opposed to the more middle-class, and (crucially) better scoring 11th School District, which encompassed Co-op City, Baychester, Pelham Parkway, Morris Park, and City Island. District 12’s problems began at the top, evidenced by a 1993 investigation, which revealed “widespread corruption and patronage”, which ultimately led the chancellor to remove the school board. When local parents were asked by reporters about the bombshell report of corruption and dirty politics, many simply replied, “what took them so long?” Indeed, the myriad of issues plaguing District 12 were well-known amongst Bronx parents. Unsurprisingly, according to a New York Daily News study published two years later, only twenty-nine percent of students in District 12 were reading at grade-level, while fewer than one-third scored at the appropriate grade-level in math (whereas District 11 scored above the city average in both metrics).

Yet, even more troubling for the young family, was the spate of violence that haunted Parkchester, built as a shield from the worst threads of urban life, during the first few years of Ocasio-Cortez’s life. In 1991 alone, there were an estimated five-hundred robberies in Parkchester. When interviewed, a local police detective mentioned that approximately seventy-five percent of Parkchester Seniors were robbed in the early 90’s, with one individual, a twenty-three year old man, robbing almost one-hundred on his own before being caught: "Sometimes we go into a building looking for one person and we end up finding three or four more. They never even reported it. They were just so happy nothing happened to them.” the detective told Newsday. Such relief was for good reason, because not everyone was so lucky. As more and more of the home robberies turned deadly, Parkchester residents began forming building patrols. As New York City experienced a record number of murders, the unsolved killings of three teenage girls, ages 13 to 17, in separate break-ins along Metropolitan Avenue in 1988 and 1990, rocked the Parkchester community to its core.

For the new parents who welcomed their daughter into the world in the fall of 1989, Parkchester remained the best of New York City’s mosaic. But, as the city’s challenges deepened, with safety threatened and education prospects eroding — the dual bedrocks of stable life for New York’s outer borough families — those with the modest means to do so, working-class people with middle-class dreams, began to leave.

They were not alone.

In the decades preceding and following the turn of the millennium, the racial and class composition of the East Bronx saw significant change. On the other side of the Hutchinson River Parkway, what had once been almost exclusively middle-class enclaves of Italian and white ethnic homeowners, had (slowly) began to diversify over the course of the 2000’s, owed to a tertiary wave of outmigration to the suburbs and beyond. The white working-class, Irish and Italian, once embedded in the fabric of apartment houses in outer borough neighborhoods like Pelham Bay, who endured their own abuses — such as the illegal dumping of toxins in their backyard, which led to several neighborhood children developing leukemia — were slowly, untethered to homeownership or no longer able to afford their mortgages, becoming extinct. As the Puerto Rican diaspora spread out throughout the Bronx, the working-class departed the South Bronx for Soundview, Castle Hill and Parkchester, while the middle-class, gradually, migrated to Throggs Neck — trading their subway rides for car commutes, and their rent checks for mortgage payments. Even the seaside village of City Island, greater than ninety-five percent white for one hundred years, once out-of-reach for the borough’s Black and Latino working-class, save for traffic-jammed weekends and overpriced fried food on the Island’s southern tip, was gradually diversifying.

However, the white ethnics who remained — those whose roots were once tied to Belmont, Williamsbridge, or Morris Park — were a testament to the changing character of the Bronx. Increasingly, they pushed eastward, beyond the Throgs Neck Expressway, into private, gated communities like Edgewater Park and Silver Beach. Having seen their neighborhoods change across several decades, the cooperators of Edgewater and Silver Beach took steps to ensure that their idyllic, waterfront communities would remain insulated, leading to a 2009 federal lawsuit alleging racial discrimination against potential black homebuyers.

“According to the lawsuit, the white woman was warmly welcomed by Ms. Lewis [the real estate agent], and was quickly shown nine available homes in both Edgewater Park and Silver Beach Gardens. The white faux buyer voiced the concern that she did not know anyone who lived there; the cooperatives’ rules say that prospective buyers must submit three recommendation letters from current residents. But Ms. Lewis replied that she would line up the necessary reference letters, adding ‘they would love you, I can tell,’ the suit said. A week and a half later, the African-American couple arrived at Ms. Lewis’s office and were almost immediately asked if they knew three people who lived there. When they said they did not, Ms. Lewis said, ‘there’s no way you’re going to get in there,’ the suit said. Ms. Lewis went on to say that Edgewater Park was ‘not wonderful for everybody,’ the suit said, adding that it was mostly Irish and Italian, ‘kind of prejudice’ and ‘like Archie Bunker territory.’” (The New York Times)

In fact, much of New York’s 14th was once considered Archie Bunker Territory — inspired by the fictional Astoria, Queens homeowner from the 1970’s sitcom All in the Family.

“Archie has a gruff, overbearing demeanor, largely defined by his bigotry toward a diverse group of individuals: blacks, Hispanics, "Commies", Freemasons, gays, women, hippies, Jews, Asians, Catholics, "women's libbers", and Polish–Americans are frequent targets of his barbs… As the show progresses, it becomes evident that Archie's prejudice is not motivated by malice but is rather a combination of the era and environment in which he was raised and a generalized misanthropy… Archie is a Republican and an outspoken supporter of Richard Nixon, as well as an early supporter of Ronald Reagan in 1976; he correctly predicts Reagan's election in 1980. During the Vietnam War, Archie dismisses peace protesters as unpatriotic and has little good to say about the civil rights movement.”

In political commentary, the Archie Bunker vote became shorthand for the bloc of urban, white, working-class men. And, during the latter half of the 20th century, many of the neighborhoods that would be represented in Congress decades later by a democratic socialist — like Astoria and Throggs Neck — were embodied by the blue-collar, Catholic, white ethnic small homeowner; many of whom despite identifying as Democrats, held relatively conservative views, particularly with respect to school busing and abortion. Their representation, at every level of government, reflected this. In the East Bronx, former police officer Mario Biaggi enjoyed unimpeachable support from both the Democratic and Conservative Parties during his two decades in Congress; as was the case with Queens Rep. James Delaney, a staunch supporter of the Vietnam War. Joe Crowley’s Queens-based Assembly District, voted for Ronald Reagan twice and Rudy Guliani thrice. Before becoming Walter Mondale’s Vice Presidential candidate, the more liberal Geraldine Ferraro was anything but — favoring the death penalty while rejecting school busing. Congressman Tom Manton, Crowley’s predecessor, opposed gay marriage as member of the New York City Council, and later earned an eighty-nine percent rating from the National Right to Life Committee during his final term in the House of Representatives. Even Crowley himself began his congressional career with lackluster support scores from Pro-Choice advocacy organizations.

Such was the constituency inherited by Joseph Crowley, when his mentor stepped aside (on the last day it was legally possible to do so) and arranged for the Assemblyman, his chosen successor, to replace him on the ballot. Effectively skipping the all-important Democratic Primary, Crowley coasted through the General Election. Yet, in a sign of things to come, Crowley’s district changed significantly during the 2002 decennial redistricting period, shifting considerably north into the Bronx — foreshadowing trouble for the Queens native. However, Crowley easily won re-election, following two (relatively weak) consecutive primary challenges. For the next fourteen years, Crowley would only face the most tepid opposition for re-election.

Perhaps hubris set in for the incumbent. Even in 2002, the district was plurality Hispanic, while the white population continued to decline. Surely, over the next decade and beyond, those trends would continue? Redistricting in New York State, frequently decided by courts rather than his former colleagues in Albany, had already dramatically changed the district in an instant. What would prevent such a phenomena from reoccurring ten years later?

And change it did. While the 2012 redistricting period, in Crowley post-mortems and Ocasio-Cortez profiles, has described the incumbent losing a political “knife fight,” the reality is far more nuanced. Crowley lobbied for an entirely Queens-based district, one that likely would have retained a small Asian-plurality, but nonetheless promised a greater degree of future security. While the court-drawn maps were not the incumbent’s first choice, they represented an improvement, as the infamous “King of Queens” regained what had once comprised his base: Astoria, Sunnyside, and Lefrak City; at the expense of Soundview, Castle Hill, and Co-op City in the Bronx. Even in a district that was less than one-quarter White, no one stepped forward to challenge the incumbent.

Yet, Joe Crowley — perhaps preoccupied with the allure of Washington, where he steadily climbed the leadership ranks of House Democrats — showed little foresight in understanding the developments afoot in his political backyard.

Astoria, Queens was no longer the home of Archie Bunker, but rather the Bernie Sanders left, in rapid ascendance following the 2016 Democratic Presidential Primary. This neighborhood, the size of a small city, which had elected Greek politicians to local and state office for decades, had also begun to change. Twenty minutes from Manhattan by train, rich with culture and food, not to mention quality schools; Astoria became an affordable destination for the college-educated millennial class, many of whom earned respectable wages in white-collar professions, but nonetheless found themselves priced out of both Manhattan’s urban core, and the many Brooklyn neighborhoods whose cultural cachet was rapidly rising — all while Astoria’s native, white ethnic population was simultaneously leaving both the neighborhood and the Democratic Party. Activated by the Sanders campaign, cohered during the early years of the Trump Administration by organizations like NYC-DSA and Justice Democrats, amidst deep-seated dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party establishment bubbling to the surface — this cohort, growing by the month in Western Queens, quickly morphed into a sleeping giant in the leadup to the 2018 midterm elections.

Across the Grand Central Parkway was Jackson Heights, the “most culturally diverse neighborhood in New York, if not on the planet." Yet, in a neighborhood where over half of residents are foreign born, many of whom are South American or South Asian, the Queens Democratic Party under Crowley showed little interest in bringing said immigrant communities into their political tent. Above Northern Boulevard, on the middle-class blocks of East Elmhurst, the neighborhood’s Black middle-class, loyal to both the County Organization and the Democratic Party at large, was slowly decreasing. Farther east was the working-poor neighborhood of North Corona. No neighborhood has more Spanish speakers, or a higher percentage of non-citizens, than the handful of blocks east of Junction Boulevard. Once a hallmark of Democratic Party organizing in New York City, dating back the days of Tammany Hall, new immigrant groups in the twenty-first century, even as they attained citizenship and the right to vote, were often dismissed due to their relatively lower turnout in local primary elections — a catch-22 which further perpetuated itself. Most damningly, in a district where half of the residents were Hispanic, and over forty-percent spoke Spanish at home, Joe Crowley never bothered to learn the native language of his constituents.

Across the neighborhoods of New York’s 14th District, there was, unbeknownst to “The King of Queens” and the atrophying machine which orbited him, a political power vacuum. Macro conditions and social forces would align, briefly, to produce the ingredients for a generational upset.

But for this moment, fleeting as it was, to be realized, the right person would have to step up. In 2011, upon graduating from college, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez moved back to the Bronx.

There would be many late night trips home on the #6 train and long waits for the express bus to Manhattan at the Metropolitan Oval; before Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was approached by Brand New Congress about running in New York’s 14th District; before she shocked the country, and maybe even herself, while becoming the youngest woman ever elected to the House of Representatives; before AOC become the most-famous three letters phrase American politics; before the land of Archie Bunker became “The People’s Republic of Astoria.”

This decision, which arguably changed the course of American politics, was not a foregone conclusion. Armed with a college-degree from a top university (she had graduated cum laude from Boston University), Ocasio-Cortez could have moved anywhere and done well for herself. At the time, both her mother and brother still lived in Yorktown Heights. Her college boyfriend (and now fiance) was from a desirable Arizona suburb. Boston, owed to the abundance of universities in close proximity, retained a steady job market for talented college-grads, even in the years following the Great Recession. If she did move back, it would be with the heaviest of hearts, as the person who “knew [her] soul better than anyone on this planet,” the man who embodied the Bronx as much as anyone she knew, passed away from lung cancer before her Sophomore year.

The question of Why: why someone with choices, on the heels of personal tragedy, would return to a place where many do not have choices — remains remarkably overlooked in the methodical chronicling of Ocasio-Cortez’s biography, despite its essential role in helping to understand her character.

Two weeks ago, Ocasio-Cortez herself began to answer why: “By the time I was in college, my goddaughter was born. I moved back to the Bronx because I wanted her to go to school… and have the confidence of being in her community. I did not want her family to have to make that choice.”

And so, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did not only return to the Bronx and New York’s 14th Congressional District – she came home to Parkchester.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was not always a top-of-the-ticket overperformer.

In 2018, she trailed several points behind Governor Andrew Cuomo, the function of Ocasio-Cortez being solely on the Democratic Party ballot line (while Joe Crowley earned protest votes under both the Working Families and Women’s Equality ballot lines), whereas Cuomo had four ballot lines to his name. Nonetheless, Ocasio-Cortez still edged the Governor in many precincts throughout Astoria, Woodside, and Sunnyside — the same gentrifying neighborhoods which turbocharged her election to Congress. In 2020, one can glean the early markers of AOC’s working-class strength in November, as her percentage (by a relatively modest, but noticeable margin) eclipsed Joe Biden across the Roosevelt Avenue corridor, Corona, and East Elmhurst. In 2022, competing in a newly redistricted iteration of NY-14 (that included far more of the South Bronx), Ocasio-Cortez outran Governor Kathy Hochul by modest margins in the new additions of Soundview, Castle Hill, Hunts Point and Longwood, while submitting her best performance yet in Parkchester, Westchester Square, and Corona.

Brief Aside: Interestingly, throughout the middle-class development of Co-op City (61% Black, 27%), Ocasio-Cortez received dozens of fewer votes(~35-55 on average), per election district, than Hochul (despite similar topline percentages), indicative of many leaving their Congressional ballot blank.

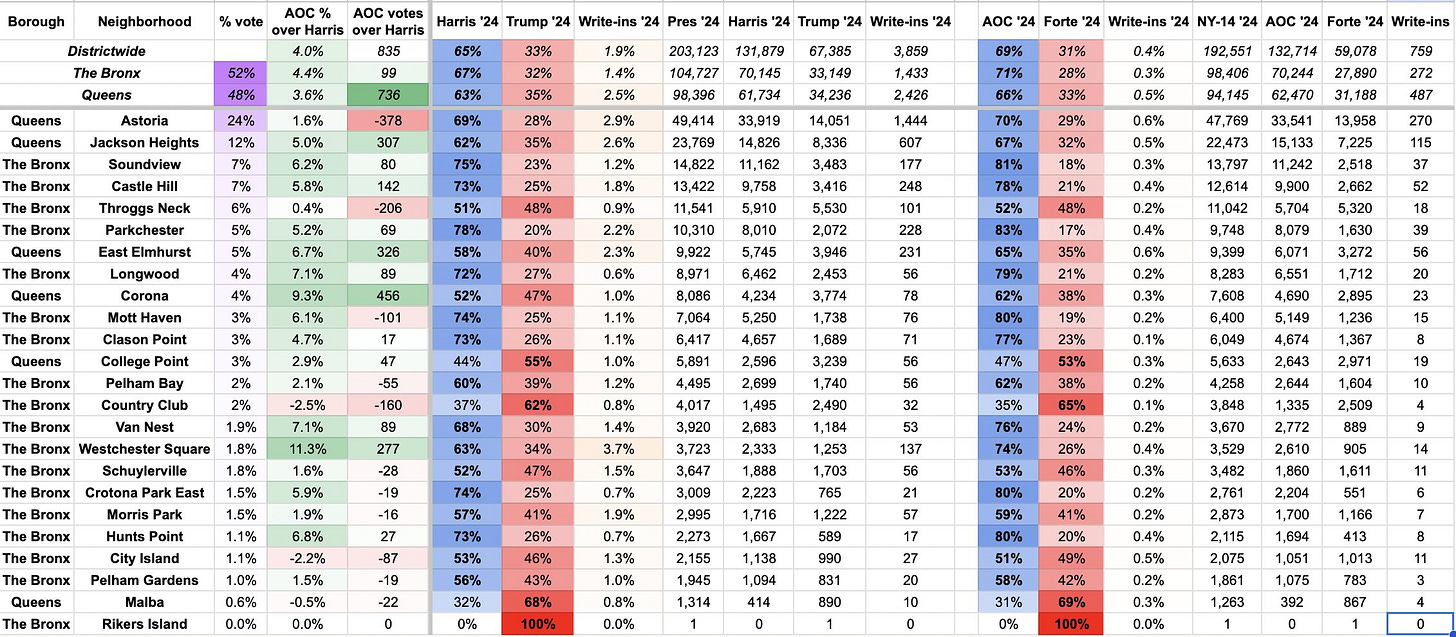

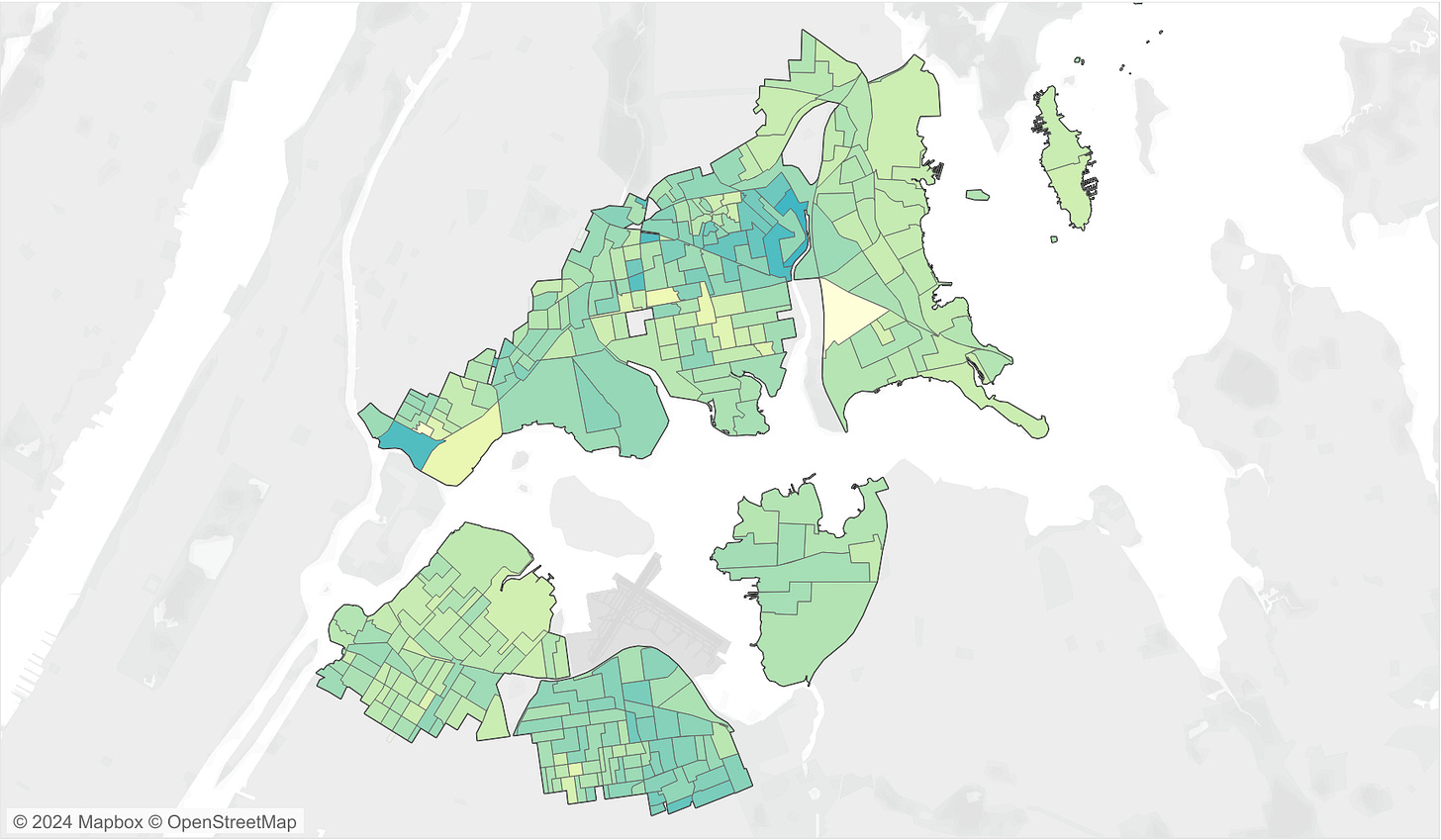

This November, in her fourth general election (and third iteration of the 14th District), Ocasio-Cortez delivered her best performance of her career — outperforming Kamala Harris by four-percent (6.5% partisan lean advantage) while earning more total votes (eight-hundred and thirty-five more) than the Vice President. In the context of New York City’s Congressional Delegation, only Grace Meng and Nydia Velázquez outperformed Kamala Harris by a greater margin. Among members of “The Squad,” only Rashida Tlaib performed better (by one-tenth of a percent). While the Bronx and Queens moved to the right — the first and second largest shifts of any county in the United States — Ocasio-Cortez held serve, and outperformed Harris in almost every neighborhood in NY-14 (see below).

However, at this point, some readers may be thinking…

“Wouldn’t this piece have been better were it based on Grace Meng or Nydia Velázquez?”

“WHY should I care so much about only 835 voters?”

“WHY did she overperform?”

Let’s go one-by-one.

The respective overperformances of both Grace Meng (+8.2%) and Nydia Velázquez (+6.3%) were the best of New York City’s Congressional Delegation; while the former proved to be the second best of any Democratic House member in Congress. In New York’s 7th Congressional District, Velázquez remains a household name with North Brooklyn’s Puerto Rican population, maintains solid relationships with the Satmar Hasidim in South Williamsburg, and has earned the good will and trust of the rising number of millennial leftists (by backing insurgent candidates for local office and lending early support to a ceasefire) who call North Brooklyn and Western Queens home. Having sounded the alarm on Asian support for the Democratic Party souring, Grace Meng, despite a catastrophic showing from Kamala Harris in her district (Eric Adams and Kathy Hochul fared no better), did not lose a single precinct in Elmhurst or Flushing; in the latter, Meng’s strong performance likely aided fellow-Democrat Ron Kim farther down-the-ballot. At a time when Democrats are hemorrhaging support from Asian, particularly Chinese communities in Brooklyn and Queens, the Representative of New York’s 6th District, who has repeatedly demonstrated an understanding of her community’s political nuances, should be at the forefront of said effort to course correct. However, while the overperformances of Meng and Velázquez were greater than Ocasio-Cortez, the latter has had to contend, in her brief six years in the political limelight, with a lifetime of negative national media — which, particularly following her initial election to Congress, not only curtailed the upstart’s surging popularity across the nation, but damaged the freshman Congresswoman, to varying degrees, in her own district. In NY-14 and beyond, AOC has name recognition on par with most Presidential candidates; and has faced more attacks the past six years than anyone not named Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, or Donald Trump. Her improvement each cycle, despite the aforementioned onslaught against her, remains noteworthy in itself.

Second, if you notice, in a series of neighborhoods (primarily in the South Bronx), Ocasio-Cortez bested Harris by several percentage points, but nonetheless gained relatively few votes compared to the Vice President. This “ballot drop” phenomena (map below), where voters cast a ballot for President and little else, occurs disproportionately in lower-income neighborhoods, and depresses the raw margin advantage enjoyed by a down-the-ballot overperformer — in this case, Ocasio-Cortez. Thus, one can discern that the eight-hundred and thirty-five vote margin separating Ocasio-Cortez and Harris is an undercount of the “AOC-Trump” voters. Such a number would not be hundreds, but thousands.

Some might be tempted to diminish Ocasio-Cortez’s advantage to that of racial voting; namely, that the incumbent, a Puerto Rican woman with a discernibly Spanish surname representing a 50% Hispanic district, handsomely benefitted in majority-Latino neighborhoods like Jackson Heights, East Elmhurst and Corona. Nor did Ocasio-Cortez face a Latino opponent, while neither Kamala Harris nor Donald Trump are Hispanic. While a factor (to an extent), such straightforward analysis would not explain the AOC-Harris performance gap between neighborhoods like Clason Point(+4.7%) and Corona(+9.3%), despite roughly similar percentages of Hispanic residents. In fact, one might surmise that Clason Point, a supermajority Puerto Rican enclave close to Ocasio-Cortez’s Bronx base, would prove more hospitable than the predominantly South American, Queens neighborhood of Corona; altogether neglecting the critical class variable which separates the middle-class, waterfront-accessible Clason Point and that of working-poor Corona. Furthermore, the millennial lawmaker also highlighted, in one of her trademark post-election Instagram stories, how Donald Trump was physically present, and campaigning in New York City, including the 14th District. Rallies in Crotona Park and Madison Square Garden, not to mention a well-publicized barbershop visit in Castle Hill, altogether amassed a tidal wave of earned media at the epicenter of the world’s most expensive media market. Whereas Kamala Harris and Tim Walz, occasionally in Manhattan for fundraisers and debate preparation, did not hold any public campaign events in New York City; (a well attended rally in Upper Manhattan’s Hamilton Heights was attended by neither). In contrast, as the author detailed extensively in a previous piece, Ocasio-Cortez and her campaign team — separate from their Congressional District office — organize across the 14th District, year-round. While Members of Congress in safely Blue districts rarely commit meaningful resources to campaign work in advance of November’s General Election, Ocasio-Cortez, armed with prodigious fundraising capabilities, has not only kept the core of her robust campaign apparatus intact for both primary and general elections, but the interim “off-years” between cycles. This institution building, throughout a predominantly working-class district (particularly in Bronx neighborhoods where the organized left sorely lacks a consistent presence) where political power is built on relationships rather than ideology, paid dividends on November 5th. If this work — door knocking, cultivating volunteers, facilitating voter registration and census response — represents the micro, there is also the macro: in this case, the potency of political celebrity, a game breaking asset possessed by few, and, arguably harnessed to it’s maximum effect by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez… and Donald Trump. On the margins, particularly in a general election (for example, one quarter of registered voters in Corona, Queens are Independent), this celebrity can transcend the traditional markers which too often bind our politics, and cut through directly to voters.

Yet, beyond the aforementioned factors, and despite the federal overtone of this election cycle, many voters, particularly in working-class neighborhoods, “consider their presidential [ballot] through the prism of local concerns.” The 14th District, detailed extensively in the previous section, contains dozens of political currents pulsing throughout each neighborhood. Here, the author strove to dig into some of those nuances through a close examination of the results separating Kamala Harris and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, in a district where Donald Trump increased his vote share by eleven percent.

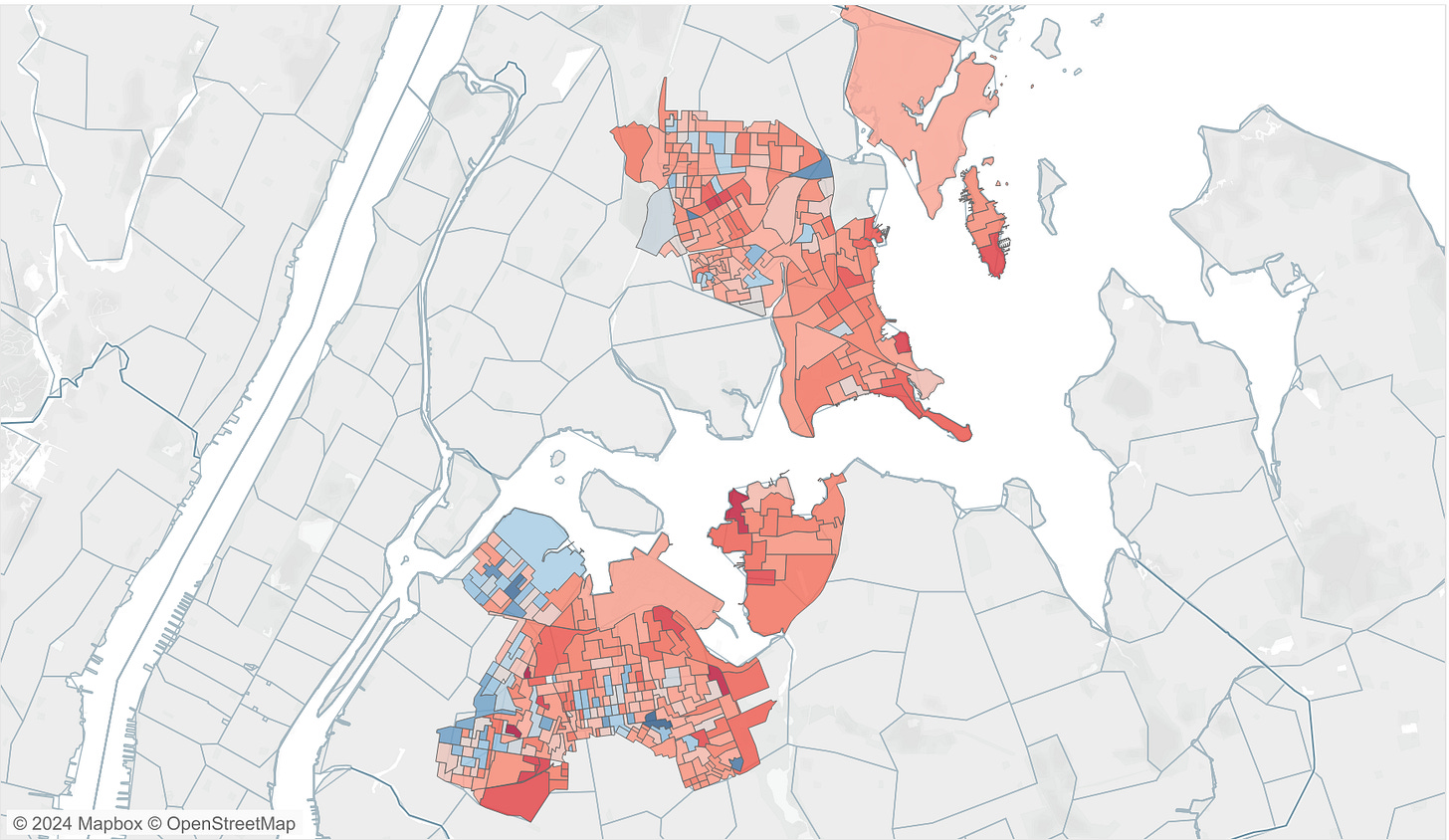

While this piece is focused on where Ocasio-Cortez outperformed the Vice President, we shall start with the neighborhoods where the inverse is true. Here (see: above map), a consistent theme emerges with respect to Ocasio-Cortez’s consistent shortcomings among the New York-native, white ethnic homeowners — be they Greeks in Astoria Heights or Italians in Country Club. In fact, Harris overperformance versus Ocasio-Cortez was largely confined to already-Red neighborhoods, like the gated-communities of Silver Beach, Edgewater Park and Malba. In these enclaves, long the sole GOP holdouts in neighborhoods increasingly awash with blue, animosity towards the Democratic Party runs high, and resentment towards Ocasio-Cortez runs even higher. After all, Archie Bunker and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have little in common.

The lone exception is City Island, one of the few genuinely purple neighborhoods in the five boroughs. Unlike the city’s other swing pockets, Democrats on City Island remain remarkably liberal, backing the insurgent efforts of both Ocasio-Cortez and Alessandra Biaggi in 2018. Here, the shared values of Islanders — inherent skepticism of real estate development (and those who take their campaign contributions), first-hand concern with respect to climate change, and embrace of public education (PS 175 on City Island is one of the best rated K-8 schools in the Bronx) — align with key issues championed by the progressive movement. However, Ocasio-Cortez has struggled in General Elections on the Island since her ascension to Congress: In 2018, Ocasio Cortez won City Island, but nonetheless underperformed Andrew Cuomo by fifteen percent, owed to Joe Crowley’s double-digit performance on the Working Families Party Line; in 2020 and 2022 she narrowly lost twice (the former due to facing Island-native John Cummings), while both Joe Biden and Kathy Hochul prevailed comfortably. And, while Ocasio-Cortez posted her best margin throughout the seaside village since 2018, City Island was the only neighborhood — save for Country Club — where she received fewer votes and a lower percentage than Kamala Harris.

Further examination also shows that Astoria, Queens — a hotbed of democratic socialism integral to Ocasio-Cortez’s defeat of Joe Crowley — failed to give their like-minded Congresswoman a significant margin over Kamala Harris. While some might attribute this result to intra-movement tension between AOC and the vanguard of the left, Astoria in the General Election — where the neighborhood’s larger share Independents and Republicans dilutes its Democratic vote share — remains much redder, particularly compared to other leftist strongholds like Greenpoint and Fort Greene, than said reputation would have one believe. The pockets of Ocasio-Cortez underperformance, particularly such concentration in Astoria Heights, the neighborhood’s last predominantly Greek-enclave; consisting of cooperatives and single-family homes, tucked between Laguardia Airport, Bowery Bay, and the Grand Central Parkway; and elsewhere throughout the homeowner-heavy blocks of the Ditmars-Steinway section, further validates this interpretation.

When comparing results across New York’s 14th District, it becomes clear, rather quickly that — absent a select few blocks of white ethnic homeowners — the vast majority of the district, most notably it’s low-income and working-class neighborhoods, gave noticeably more support to Ocasio-Cortez, amidst an era of polarization where ticket-splitting is in decline.

Across the district’s South Bronx corridor — stretching from Port Morris to Soundview — Ocasio-Cortez outperformed the top-of-the-ticket between six and seven percent. Such margins were consistently replicated in public housing developments in Mott Haven, Castle Hill, Throggs Neck, and Astoria.

In Queens, Donald Trump flipped several Hispanic-majority precincts in Jackson Heights and East Elmhurst — blocks that had not delivered majorities to any Republican, let alone a Presidential candidate, this century. On the same ballot, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did not lose a single election district.

Yet, the two neighborhoods of New York’s 14th that saw the most pronounced swing to Trump — and the largest chasm between Harris and Ocasio-Cortez — came at opposite ends of the district, with markedly different, but nonetheless instructive, reasons as to why.

The Westchester Square section of the Bronx and the Queens neighborhood of Corona saw the most “AOC–Trump voters” of anywhere in New York’s 14th District.

The former, on the outskirts of Parkchester, lies on the other side of Castle Hill Avenue, stretching as far east as the rail yard that abuts Westchester Creek. Once an industrial neighborhood, Westchester Square, like its neighbor to the west, has become both a Bangladeshi and Latino enclave in the twenty-first century. However, unlike their Parkchester neighbors, who are more likely to own cars, let alone their apartments through the cooperative, the residents of Westchester Square remain renters, overwhelmingly, whose transportation is largely confined to either the #6 train (which rumbles along the neighborhood’s spine), or the hub of local buses that service the transit-desert corridor of the East Bronx. Here, on the side streets of Saint Peters Avenue and the primary thoroughfare of East Tremont Avenue, one will find the Masjids which service the most-concentrated Muslim population in the Bronx; community members organizing the neighborhood’s South Asian population through DRUM (Desis Rising Up And Moving); four-family brick homes and modest apartment houses (some with charming courtyards); and Halal grocery stores and Spanish-language small businesses side-by-side with McDermott’s Pub and Cestra’s Pizza — when taken together, perhaps no better embodiment of Westchester Square’s past and present.

A short walk from the Zerega Avenue train station, Ocasio-Cortez has maintained her campaign-office, year-round, in Westchester Square since her election to Congress. This November, as Muslim and South Asian communities across New York City, angered by the Biden Administration’s failure to secure a lasting ceasefire in Gaza, eschewed the Democratic Party by the dozens (voting for Donald Trump, writing-in Jill Stein, or simply staying home), Westchester Square proved no different. While Joe Biden had won more than eighty-percent of the vote in Westchester Square four years ago, Kamala Harris struggled to break sixty-five percent in most election districts. While voter turnout decreased across the neighborhood, Donald Trump, who visited the nearby Knockout Barbershop in Castle Hill, managed to increase his raw total in Westchester Square by several hundred votes.

However, the erosion of support for Kamala Harris in Westchester Square did little to damage the standing of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Here, in a community untouched by gentrification in an oft-overlooked corner of the Bronx, is the hub of her campaign operations. Ocasio-Cortez’s early support for a ceasefire in Gaza, well-known inside political class circles, still needed to reach her working-class neighbors in Westchester Square: “you have to meet people where they are.” And, whether it came in the doorway of an apartment, inside the mailbox, or along Westchester Avenue as the subway clattered overhead; the people of Westchester Square, oftentimes more than once, would be met where they were in the closing months of 2024. And, when they were met, they would be greeted with a multilingual piece of literature — in English, Spanish, Bengali, Hindi — detailing their Congresswoman's advocacy for a Ceasefire.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Supports a Ceasefire in Gaza

“Alexandria has demanded a ceasefire since the start of the war in Gaza. She has also denounced the forced starvation on 13 million Palestinians by the Netanyahu government as genocide. Alexandria has condemned Netanyahu's government for participating in alleged war crimes, such as deployment of white phosphorus in populated areas, which according to Amnesty International should be investigated. She also condemned the brutal attacks by Hamas against Israeli civilians on October 7. She was one of the original co-sponsors of the NCTW Ceasefire Resolution, which calls for a bilateral ceasefire, an end to Israel's blockade of food, water and humanitarian aid in Gaza, and the release of all hostages.

Alexandria has pressed the Biden administration to take immediate steps to stop the genocide unfolding in Gaza, including enforcing compliance with US law and humanity standards to halt the transfer of US weapons to the Israeli government and voted against a Republican bill that provides millions to the Israeli army. The mass starvation of one million Palestinians comes on top of the slaughter of at least 30,000 others, 70% of which were women and children. Every devastating loss is a world extinguished. The indiscriminate killing of civilians will not bring stability or security to anyone in the region. The US government has a responsibility to prevent further atrocities and must maintain its commitment to human and civil rights.”

Thus, it should come as no surprise that when this Bronx neighborhood cast their ballots this November, while Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez may not have been at the top-of-the-ticket, she nonetheless remained top-of-mind to the voters who lived in Westchester Square. Overall, not only did Ocasio-Cortez outperform Harris by more than eleven-percent, approximately one-fifth of Republican Presidential voters in the neighborhood also cast their ballots for the Democratic Congresswoman from New York’s 14th District. In one election district in particular — home to the largest Muslim population of any such precinct in the Bronx — more than thirty-five percent (and potentially, as high as forty-percent) of voters who cast their ballots for Donald Trump, also did so for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. In the entirety of the Bronx — including the rest of the 14th District, and the neighboring 13th (Adriano Espaillat), 15th (Ritchie Torres), and 16th (George Latimer) Congressional Districts — no Member of Congress outperformed Kamala Harris on any of the borough’s blocks, more than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did in Westchester Square.

Across the East River in Corona; a neighborhood bounded by Junction Boulevard to the west, Northern Boulevard to the north, and the Grand Central Parkway to the east (the 14th District ends at Roosevelt Avenue); the political zeitgeist, and why hundreds of the neighborhood’s predominantly low-income, Hispanic residents chose both Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Donald Trump, was less cut-and-dry.

Having voted overwhelmingly against Trump in 2016, the political shift afoot in Corona, perhaps the clearest of any neighborhood in the five boroughs, signified the depths of Democratic decay with the Latino working-class — embodied by several precincts, particularly along Roosevelt Avenue, which had delivered between eighty-and-ninety percent of their votes to the Democratic nominee eight years ago, outright flipping to Donald Trump this November.

In the days following November 5th, as Democrats reckoned with their worst Presidential result in New York City since 1988, many — elected officials, journalists, and the political/consultant class — ascribed said poor performance to decreased Democratic turnout. At the ensuing Somos Conference, State Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie told reporters that the shift to Trump “may have been a mirage,” due to the aforementioned voter turnout dynamics. Remarkably, many Democrats in New York City — not all, but far too many — seemed to be downplaying that a genuine shift, one large enough to inspire a consequential discussion, had occurred within the electorate, nowhere moreso than amongst the multiracial working-poor and lower-middle class of the outer boroughs.

First, while voter turnout decreased in New York City compared to the 2020 Presidential Election, the distribution of the vote in each respective Assembly District compared to the citywide total, remained relatively unchanged between 2020 and 2024; in contrast, during the 2022 midterm, relative voter turnout cratered in lower-income and working-class Blue neighborhoods, allowing the consistently, higher-turnout Red neighborhoods to increase their influence over the electorate. Second, using the 2020 Presidential Election (as many observers have) as a baseline for raw voter turnout paints an incomplete picture, given it remains the highest turnout election in U.S. History (not to mention, the highest in New York City since 1964), and occurred (largely before) the drastic population loss (-550K residents) experienced by New York City over the past four years. In fact, the 2024 Presidential Election was the city’s second-highest turnout Presidential Election since the aforementioned ‘64 tilt between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater. In 2016, Donald Trump received 37,797 votes in the Bronx (9.6%), eight years later, he banked 98,174 votes (26.97%) in New York’s lowest-income county; similarly, the Republican-nominee won 149,341 votes (21.76%) in Queens during his first campaign, whereas this November, the President-elect earned 264,628 votes (36.96%) in the most diverse county, in every sense of the word, in the United States. Such staggering increases in Donald Trump’s raw support, had little to do with Democrats staying home.

This analysis, so widely distributed in the wake of November 5th — that Republican gains with Latino and Asian communities in Brooklyn, Queens, Upper Manhattan, and the Bronx could be primarily attributed to decreased Democratic voter turnout — fell flattest in neighborhoods like Corona: blocks where more than sixty-percent of voters are registered with the Democratic Party, and less than ten-percent are registered as Republicans. In fact, on the streets of Corona inside the 14th Congressional District, Trump gained, on average, more than one-hundred votes per precinct compared to 2020.

But statistics alone do not come close to telling the story of Corona. In dozens of conversations (some in English, most in Spanish) with those who live there (as well as many who hang their hat in nearby East Elmhurst and Jackson Heights) — at Traver’s Park, Gorman Playground, and the streets of Northern Boulevard and 37th Avenue — patterns began to emerge. “Roosevelt Avenue,” the primary thoroughfare connecting Jackson Heights and Corona beneath the #7 train, was a local buzzword synonymous with prostitution and lawlessness — the oft-repeated, always animating phrase as to one’s burning dissatisfaction with the Democratic Party. Many Latino men, the subject of great inquiry following nationwide shifts to the GOP, confessed to being, as recently as four years ago, consistent voters for Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden. Yet, perhaps more troubling to Democrats was what the author heard from those who could not vote. Several individuals, mainly men, currently residents on green card visas, expressed a discernible eagerness to obtain citizenship in the next couple of years, so as to vote for Donald Trump in four years. A woman in her mid-40’s, living in Queens for over two decades without documentation, professed her support and admiration for Donald Trump — in a manner which reflected earnest belief, rather than overzealous fandom. Relatively aware of Trump’s rhetoric with respect to potential mass deportations, which could potentially target her (or her family), she expressed little fear, with words the author can recall weeks later: Hacer lo correcto — “I do the right thing.”

As those who have petitioned to gain ballot access can attest, even finding registered voters can prove difficult — particularly, in a place like Corona, with one of the highest non-citizen populations in New York City. The author’s task, finding someone who voted for both Donald Trump and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, even on blocks where significant ticket-splitting occurred, without a fancy polling company to do advance work, was akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

Nonetheless, at the end of a long day, a short walk from the steps of the 111th Street entrance to the #7 train, the author had the opportunity to speak to a thirty-one year old woman, accompanied by her two children. For the sake of preserving the subject’s anonymity, the author will use the alias of Lina. A lifelong resident of Corona, Lina now lives with her husband a few blocks away from where she was raised. While Corona is not thought of as a stroller neighborhood — like Brooklyn’s Park Slope or Manhattan’s Upper West Side — the author encountered many strollers, pushed by young mothers, on the streets of Corona. Lina, pushing her youngest son, blissfully asleep in his stroller, with her nine-year old, Burger King crown atop his head, in tow, was no different. She wore a jean jacket over a white shirt, with impressive, jet-black, curly hair. Registering to vote at nineteen, in advance of the 2012 Presidential Election, she did so as an Independent (unaffiliated) — but nonetheless supported Barack Obama (she has never switched her party registration). Her story, upon an exhaustive review of public records, checked out.

“I wish it was like when I was growing up,” she told me.

Once a predominantly-Italian neighborhood with a large contingent of middle-class Black families during the post-war period, Corona’s Hispanic population — now, exceeding eighty-percent of the neighborhood — began to take shape throughout the 1970’s. Dominicans, like Lina’s parents, were among the first wave of Latino immigration to Corona, followed by an influx of South Americans, particularly Colombians and Ecuadorians, in the 1990’s. Yet, the Corona of her youth, while described today with a tinge of nostalgia, was not without hardship — as was often the case for many working-class, majority Black and Latino neighborhoods three decades ago; (our earlier reflections on the Parkchester of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s early years, further underscores this theme). Drug wars rooted in Colombia spilled into Corona (and neighboring Jackson Heights), and while dozens of late-night executions behind-closed-doors occurred throughout the neighborhood, residents took comfort that at least the killings were not random. A neighborhood in ethnic and economic transition, Corona was not spared the violence that, in many instances, accompanied such demographic change in New York City’s outer boroughs. Yet, while the murders of Yusef Hawkins in Bensonhurst and Michael Griffith in Howard Beach, two Black men assailed by gangs of white youth, were seared into the city’s consciousness during the mid-1980’s (and many decades thereafter); the gruesome murder of Manuel Mayi Jr, an 18-year-old Queens-college student of Dominican descent, brutally beaten to death by three youths at the heart of the neighborhood, is remembered outside of Corona (and Latino media) to a lesser extent.

If there were problems plaguing Corona, and, by every available account, there certainly were — the world beyond the Spanish-speaking Queens enclave rarely took notice. Following the most pronounced shift to Donald Trump of any neighborhood in the five boroughs, New York Magazine described Corona as “effectively New York’s flyover country.”

Not since two Queens-natives, attorney Mario Cuomo and journalist Jimmy Breslin, championed the cause of Corona’s “Fighting Sixty Nine” — in the early 1970’s, 69 homes were on the brink of being bulldozed to build an athletic field adjacent to a proposed high school, Cuomo negotiated a deal with the administration of John Lindsay, saving all but 13, and was lionized as a “local hero” by Breslin — had Corona, as the neighborhood did following November 5th, captured the attention of New York City’s political class. Over the past five decades, none of the neighborhood’s City Council Members, State Senators, or Assembly Members have ever advanced to higher office. The most notable of the aforementioned dozens of elected officials, Hiram Monserrate, was infamously expelled from the State Senate for assaulting his girlfriend; (the incident was caught on video, Monserrate was convicted on a third-degree assault misdemeanor count. Disgraced, he was later convicted on separate federal corruption charges, serving twenty-one months in prison. Monserrate continues to be a perennial candidate for office in Corona). With the highest percentage of non-citizens of any New York City neighborhood, Corona, despite exceeding one-hundred thousand residents, has relatively few votes to deliver, and thus, lacked the requisite electoral power to influence politics at the highest levels. The road to Gracie Mansion ran through Central Brooklyn or The Upper West Side — not Corona, Queens.

Across New York City’s many working-class communities, political ideology is a luxury many cannot afford. In neighborhoods like Corona, connection — durable, time-tested relationships to individuals and institutions — carries the political day. Here, incumbents, particularly those boasting a formidable warchest and supported by organized labor, are traditionally favored to win resoundingly, much less prevail altogether. However, the dozens of Democrats in Corona who came to the polls on June 25th, 2018, thumbed their noses at this political orthodoxy. On blocks orbiting Roosevelt Avenue that would be lost to Donald Trump six years later, many ignored Joe Crowley’s institutional support — for he, they felt, had ignored them — and instead put their faith in a dynamic upstart, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Less than two years later, Ocasio-Cortez would be standing alongside Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer at Corona Plaza (the popular street vendor and transit thoroughfare at 103rd Street & Roosevelt Avenue), at a time when this Queens corridor earned the dubious distinction as the hardest hit community in New York City by the COVID-19 pandemic, to tell New Yorkers — especially the quarter of a million who call Corona, East Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights home — that, as they navigated unprecedented levels of loss, funeral expenses should not be added onto the already crushing burden of suddenly losing a loved one.

“Since the pandemic, things have gotten worse.”

Reliably Democratic for decades (outside of the middle-class, predominantly Black belt across the borough’s more-suburban Southeast; Corona was, as little as eight years ago, the bluest neighborhood in all of Queens), Corona’s fast-paced shift to the right cannot be understood without an accounting of how the pandemic’s havoc, nothing short of devastating at the height of COVID-19, continued to linger far beyond that infamous calendar year. Unsurprisingly, Donald Trump’s gains in Corona date back to November 2020.

In his election postmortem, Simon van Zuylen-Wood provided an exhaustive and succinct account of the issues that continue to plague Corona, Jackson Heights, and the Roosevelt Avenue corridor — four years after the pandemic’s height.

“The essential issue there, as an aide to one local Democratic politician puts it, is that ‘the underground economy is completely overground.’ Roosevelt Avenue and its surroundings have become saturated with two types of new arrivals: unlicensed street vendors selling food or merchandise and sex workers soliciting customers outside makeshift brothels. There is consensus among elected officials and residents that many of the women are sex-trafficking victims from Central and South America working to pay off their debt to smugglers. These factors have led to what residents describe as a quality-of-life disaster, coinciding with an uptick in crimes such as robbery and felony assault, which increased locally by about 50 percent in the past two years.” (New York Magazine)

Roosevelt Avenue is the path taken by Lina, every weekday, on her walk to and from work at a nearby health insurance agency. At her job, she helps those with (and without) documentation access benefits (available to those regardless of citizenship status) like SNAP. Far closer to home, she divulged that not all members of her extended family, in New York City and beyond, remain in the United States legally. In dozens of such conversations that day, the author could feel when, as the topic broached immigration, when resentment — towards the neighborhood’s newest arrivals — began to surface. Speaking to Lina, no such resentment was detectable; rather, the author felt that she held genuine empathy for her neighbors without documentation. Well-aware of Donald Trump’s trigger-happy rhetoric of deporting undocumented immigrants, and the potentially disastrous effects such an effort could wrought on her neighbors, Lina expressed doubt, not borne of defensiveness or fear of contradiction, but of a true belief that Trump — through bureaucratic red-tape or an overall reluctance to follow-through on such an ugly act — would not actually carry out this effort.

For many in Corona, the Republican-nominee’s misgivings still proved cause for concern, but four years of Democratic governance at the local and federal level — four years when every aspect of neighborhood life grew worse — proved even more concerning. The threat of Donald Trump, a fever-pitch in 2016 and 2020, dramatically lost salience across working-class Latino and Asian neighborhoods in New York City.

Case and point, in the election district where Lina lives, less than fourteen-percent of voters (eighty in total) backed Trump eight years ago. By 2020, while that number more than doubled to two-hundred votes, the Republican nominee barely eclipsed twenty-five percent. This November, Lina and three-hundred and twenty-four of her neighbors voted for Donald Trump, enough for a majority — capping off a remarkable eight year reversal of fortunes for the Republican nominee. One nearby precinct (between 102nd/108th Street & 37th/39th Avenue), was won by every Republican candidate on the ballot: President, Senate, and Queens Surrogate Court, except Congress.

As the multi-racial working-class abandoned the Democratic Party, they did not abandon Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

The defeat of Kamala Harris, swift (the Democratic nominee lost all seven swing states) and decisive (for the first time, Donald Trump won the popular vote), has opened the door for a genuinely competitive, and relatively wide open Democratic Presidential Primary in 2028 — the first race in a generation without a prohibitive, early favorite — at a time when dissatisfaction with the political establishment is peaking.

However, the progressive movement, after experiencing rapid growth and newfound political power at the height of the Bernie Sanders era, has struggled to find comfortable footing during the Biden Administration, as lawmakers and activists weather electoral backlash, further spurred by intra-Democratic Party polarization with respect to the War in Gaza. This summer, both Jamaal Bowman and Cori Bush, two Congressional “Squad” allies of Ocasio-Cortez, were defeated by moderate, Pro-Israel challengers heavily financed by AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee). The former’s defeat in the neighboring NY-16 Congressional District (Co-op City, Edenwald, Westchester County), despite Ocasio-Cortez’s best efforts to save the doomed incumbent, will echo in progressive circles for years to come.

Now, in a moment of disorganization nevertheless ripe with opportunity, who on the left will step up to fill the void?

This Tuesday, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, by her critics' own admission one of the most skillful orators on Capitol Hill, attempted to ascend to Ranking Member of the House Oversight Committee. However, amidst “generational” change afoot in the House Democratic Caucus — the thirty-five year old congresswoman was rebuffed by the leadership-heavy Steering Committee, before losing the overall Caucus vote by a margin of 131 to 84. Despite the support of both the Congressional Progressive Caucus and Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Ocasio-Cortez was undone by the master of institutional power, Rep. Nancy Pelosi. Once the three-term lawmaker entered Pelosi’s crosshairs — by most accounts, the chief architect of Joe Biden’s abrupt withdrawal from the Presidential campaign — Ocasio-Cortez’s chances of victory, even against a seventy-four year old opponent recently diagnosed with esophageal cancer, were slim.

While some might shade Ocasio-Cortez’s efforts to build institutional power, especially after losing the ranking member vote, such is the necessary slow-grind towards passing impactful legislation and multiplying one’s influence in America’s most gridlocked body. Nonetheless, those exclusively championing said “insider” strategy, must consider the reputational fallout such a move might entail — particularly among the disillusioned masses who value the anti-establishment notes frequently played by AOC on her ascension to superstardom — while reckoning with the notion that the congresswoman’s greatest strength has always lied with the voters themselves, not D.C. power brokers.

In his speech to the House Democratic Caucus nominated Ocasio-Cortez to become Ranking Member, Rep. Pat Ryan, who bested Harris by eleven-percent in his Hudson Valley-based Congressional District, may have said it best: “All of our campaigns should be about showing the American people that we fight FOR them, and AGAINST anyone who would do them harm. Nobody encapsulates that more than Alex.”

While Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez cannot win the day against Nancy Pelosi on Capitol Hill, at least not yet, the Congresswoman from New York’s 14th District can win the hearts and minds, to an extent few politicians can, of the electorate most rapidly fleeing the Democratic Party: the urban working-class.

The epicenter of the working class exodus: New York City. And, at the fulcrum of Democratic losses, in the cultural, financial, and media capital of the United States, a vacuum has opened — which could signal the future course of the Democratic Party. While some might be inclined to look ahead to the midterm elections, by then New York City will have both a new Mayor (prediction: stamped) and City Council Speaker (as well as what looks to be a competitive race for Governor, potentially opening up the adjacent Bronx-based Congressional District in the process). Already, former Governor Andrew Cuomo and Rep. Ritchie Torres, have stepped into the proverbial vacuum amid rumored interest in respective runs for higher office, dialing up their fervent criticisms of the progressive left in the process.

Throughout her brief career, Ocasio-Cortez’s intervention in local politics has been relatively cautious. So as to maximize the weight and impact of her endorsement, she supports candidates for office relatively sparingly. However, when she chooses to put her weight behind a particular campaign, her impact cannot be understated. During the previous citywide election cycle (2021), Ocasio-Cortez lent early support to Brad Lander’s Comptroller campaign, headlining a series of (English & Spanish) television advertisements, which helped the Park Slope City Council Member prevail in a come-from-behind victory against Speaker Corey Johnson, once a close ally of Joe Crowley. Later in June, it was the last-minute endorsement from Ocasio-Cortez that tripled Maya Wiley’s polling numbers, virtually overnight, spurring the civil rights attorney to a second-place finish (on the first ballot) in the Mayoral Primary. As machines disintegrate, consultants replace organizers, and political power becomes increasingly concentrated in Midtown Manhattan offices, legacy media spaces, and closed-door rooms, at the expense of neighborhoods and communities — AOC can break-through to voters, against the likes of Eric Adams and Andrew Cuomo, in a way no one else can.

However, if one was hoping the author would share an “AOC for Mayor” (or Governor, Senator, or President) hot take, they would be sorely disappointed. Rather, this is a Call To Action. Three years ago, no institution, sans The New York Times Editorial Board, exerted greater influence on the outcome of the Mayoral race than Ocasio-Cortez. Now, with the Gray Lady’s influence diminished following the Editorial Board’s much-maligned decision to discontinue local endorsements, the media vacuum, increasingly the medium that crowns the victor in such contests, only grows.

While Comptroller Brad Lander and State Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani have emerged as early contenders to lead the progressive bloc, both could benefit from the deliberate intervention of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Lander, a self-styled “policy wonk” and “pro-growth, progressive zionist,” has already won citywide office (in part due to Ocasio-Cortez’s early backing), the Comptroller is focusing heavily on his managerial bona fides with the hopes of threading the needle between technocracy, good-government liberalism, and the progressive grassroots (that neither Maya Wiley, Kathryn Garcia, nor Scott Stringer ever could). However, Lander’s electoral strength does not lie in the multi-racial, working-class neighborhoods of New York’s 14th District; nor can the mild-mannered progressive, amidst Donald Trump’s looming second term, comfortably play the anti-establishment notes that are now, back in rhythm. Notes that Zohran Mamdani has no trouble tapping into. In fact, by the author’s estimation, Mamdani is the only remaining New York City elected official who can rival the oratory spirit of apex-AOC. While Ocasio-Cortez may have difficulty assuaging those whose class interests feel threatened by a democratic socialist, she could greatly aid the three-term Assemblyman from Astoria, whose name recognition (or lack thereof) will prove to be an obstacle in overcoming the likes of Cuomo and Adams, on his quest to reach voters. How Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez manages the most high-profile political contest of 2025, and to what extent she wields her political power, will be one of the most important threads in dictating New York City’s next Mayor.

And, beyond media savvy, ideological kinship, or any single election cycle, Ocasio-Cortez has the bona fides to assertively lead on the burning question of Where New York Democrats Go From Here. While her support is often reduced to millennials, college-graduates, and self-identified progressives — the reality of her resonance spans far beyond those narrow boxes. As Democrats hemorrhaged support with Hispanic, South Asian and Muslim voters, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez delivered her greatest overperformance compared to Kamala Harris in neighborhoods and election districts where those voters constituted a majority of the electorate. This influence amongst the urban working class, which spans every corner of the country, is most pronounced in the municipality she calls home.

While the progressive movement has suffered recent setbacks, conditions amidst our current political era are anything but fixed.

“There are great historical forces which make things the way they are, and to an extent, every individual is subject to them. But there are some individuals who ride the crest of the social forces, and turn them in their direction.”

— Robert Caro

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Excellent as always, Michael!

Great call to action at the end - really underlines the stakes here