New York City's Red Reckoning

Republicans continue to make inroads with Latino, Chinese, and South Asian communities in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Can Democrats stop the realignment?

With more than 98% of precincts reporting, Kamala Harris is polling at 67.7% in New York City — the worst performance for a Democratic Presidential candidate in the five boroughs since 1988.

In 2016, Donald Trump won 17% of the vote in New York City. Four years later, that figure rose to 22.7%, the best Republican Presidential performance in the municipality since the re-election of George W. Bush. This November, Trump surpassed thirty-percent in the five boroughs — exceeding the ambitious Republican benchmark set by Long Island Congressman Lee Zeldin two years ago. While the GOP had expanded their influence across New York City in the aforementioned midterm, Trump’s strong performance in the higher-turnout Presidential Election cements their recent gains. And nowhere was this current felt more than across the working and middle-class Latino and Asian neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx.

Democrats from Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine to Parkchester Assemblywoman Karines Reyes described the moment as a “reckoning.”

The first step — one of many — is a clear-eyed, exhaustive review of where Democrats lost in the five boroughs.

While numbers and trends are critical to our understanding of the realignment underway in New York City (one which has potential to forever alter politics in the Empire State), the author strove to intersperse his own experiences walking these very streets — with the hope of reminding each reader, as well as himself, that the psyche of a neighborhood, or the everyday lives of the people who call it home, cannot be properly quantified by statistics alone.

Let’s begin in what used to be New York State’s bluest county, the Bronx — an honor that now belongs to well-heeled Manhattan, which serves as the perfect metaphor, given Democrats have been hemorrhaging support in New York’s lowest-income county since 2016. On Tuesday, those chickens came home to roost, as Donald Trump increased his vote share here, on the streets of Fordham Road and Grand Concourse, more than any county in New York State.

AD77 — Highbridge, Concourse, Morris Heights

AD78 — Bedford Park, Belmont, Kingsbridge Heights

AD79 — Morrisania, East Tremont, Melrose, Crotona Park East, Claremont Village

AD80 — Morris Park, Van Nest, Pelham Parkway, Pelham Gardens, Norwood, Allerton

AD84 — Mott Haven, Hunts Point

AD85 — Soundview, Clason Point, Longwood

AD86 — University Heights, Fordham, Tremont

AD87 — Parkchester, Castle Hill, Westchester Square, West Farms

The 86th Assembly District, a collection of low-income, predominantly Dominican neighborhoods in the West Bronx, supported Hillary Clinton by an overwhelming 89% margin eight years ago. Here, over ninety-five percent of residents are renters, the highest-figure in New York State, while a majority of the housing stock is either rent-stabilized, or subsidized with vouchers. Over forty-percent of people in the 86th Assembly District have a disability, which ranks in the 97th percentile of all legislative districts in the United States. These neighborhoods — University Heights, Fordham, Tremont — saw the most pronounced shift from Clinton to Biden of any Assembly District in the five boroughs: greater than a twenty-percent swing in vote share. Four years later, that trend continued to an astonishing extent, to the tune of thirty-three point swing to the right; the largest shift of any district in New York City, once again — totaling, altogether, a fifty-four percent swing right over the past eight years.

Adjacent Bronx neighborhoods, encompassed by both the 77th Assembly District; which includes the historically-Black neighborhood of Highbridge (now home to thousands of African-immigrants) and the Dominican-heavy (and low-income) community of Morris Heights; and the 78th Assembly District; home to the working-class, plurality-Dominican neighborhoods of Bedford Park and Kingsbridge Heights; have seen forty-four and forty-seven percent shifts to Donald Trump since 2016.

Despite Tony Hinchcliffe’s viral reference to Puerto Rico as an “Island of Garbage,” Donald Trump’s support increased by double-digits in several historically-Puerto Rican neighborhoods in the South Bronx — like Mott Haven, Hunts Point, and Soundview. On the middle-class peninsula of Clason Point, colloquially referred to as “Little Puerto Rico,” complete with waterfront condominiums, townhouses, and two influential homeowner’s associations, support for Trump increased by 10-15% in each election district.

Off the 6 train line, in the industrial neighborhood of Westchester Square, a hub for bus service in the transit-desert East Bronx, called home by working-class Latinos and Bangladeshis (many of whom are Muslim), Kamala Harris ran nineteen-percent behind Joe Biden’s 2020 vote share. Sharing ballot line A and D with Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Harris consistently underperformed the popular, pro-ceasefire Congresswoman by ten-percent throughout the neighborhood.

While the hardships of inflation were felt across the five boroughs, it was in the Bronx, New York’s lowest-income county, where such pain cut the deepest. As Democrats lost support across the country from those without a college-degree, it was throughout the working-class and working-poor neighborhoods of the Bronx — where less than twenty-percent of residents have a college-education — that such shifts right were most pronounced in New York City. Here, in police precincts with some of the highest crime rates in the five boroughs, a law-and-order message — be it in a Democratic Primary or General Election — relentlessly focused on curbing disorder, has resonated.

Yet, the story of a borough, it’s mosaic of neighborhoods, and the people who call it home — simply cannot be told only by statistics or figures.

For instance, the 79th Assembly District in the South (Central) Bronx, is far more than its thirty-seven percent swing to the right outlined in the above table. Nor would it be enough to merely observe that this collection of low-income, working-poor Black and Latino neighborhoods has some of the lowest voter participation in New York City. Here, the district’s shocking asthma rate, owed to the legacy of Robert Moses, which ranks in the 99th percentile of all such legislative districts in America, does not represent the beginning, nor the end, of the challenges faced by those who live here.

The author will attempt, to the best of his ability, to dig a little deeper, while painting a picture — based on his experiences walking these neighborhoods, block by block — of the conditions that might cause Democrat support, once unimpeachable across each precinct, to decline precipitously.

New York’s Seventy-Ninth Assembly District includes the historically-Black, now plurality Latino, neighborhood of Morrisania; Charlotte Gardens, a handful of modest houses featuring green-grass front yards, once visited by President Jimmy Carter after the Bronx drew international headlines for burning; not to mention the well-documented One Mile of East Tremont north of the Cross Bronx Expressway. Here, many apartment houses bear the ominous warning “Attention: Patrolled by the NYPD’s ‘Operation Clean Halls’ trespassers may be subject to arrest” — the legacy of an allegedly discontinued program where the NYPD would patrol inside private buildings in high-crime neighborhoods. While the practice was banned in 2020, a federal monitor found that such initiatives did not cease while “possibly targeting people for stop and frisk.” The author, once eager to speak to residents of East Tremont about the Cross Bronx Expressway, quickly found that each conversation began, as sure as it ended, with talk of crime and the diminished quality of life throughout the neighborhood. The routine of waking up, hustling to work (both the B/D or 2/5 trains are a fifteen-to-twenty minute walk away), and returning home, only to keep to oneself, for fear of going outside at night time — described over-and-over again to the author, spoke of profound loneliness. With each block, certain buildings were pointed out as to where groups of young men, described as “gangs,” would congregate in lobbies. Without fail, the author was always cautioned to make sure he reached the subway station by sundown. When asking as to why, if they were so deeply-unhappy, they did not move away, most cited they did not have a choice, tied to their rent-stabilized apartment or voucher program — those young enough, with hope of attaining the financial freedom to eventually do so, promised they would leave at the first chance.

Speaking to a Black mother and her middle-school aged daughter, the author was told of how they used a relative’s address so the daughter could attend a better public school, farther away.

“It must be difficult going to school far away from where you live — if you went to school nearby you could make friends in your neighborhood.”

“I wouldn’t want to make friends here. It’s not safe.”

AD23 — Ozone Park, Howard Beach, Rockaway Beach, Breezy Point

AD24 — Richmond Hill, Terrace Heights, Briarwood, Windsor Oak

AD25 — Fresh Meadows, Oakland Gardens, Utopia

AD27 — Kew Gardens Hills, College Point, Whitestone, Beechhurst, Electchester

AD30 — Woodside, Elmhurst, Middle Village

AD34 — Jackson Heights, Ditmars-Steinway, Astoria Heights

AD35 — East Elmhurst, North Corona, Lefrak City

AD38 — Woodhaven, Glendale, Ridgewood

AD39 — Corona, Elmhurst, Jackson Heights

AD40 — Flushing, Linden Hill, Murray Hill

While the Bronx experienced the largest shift right of any county in New York State, the ethnic and immigrant melting pot of Queens, accurately nicknamed “The World’s Borough,” was not far behind.

The 35th Assembly District, which stretches from the historically-Black, homeowner-heavy East Elmhurst to the immigrant neighborhood of North Corona — the latter greater than ninety-percent Hispanic, with the largest concentration of Spanish-Speakers in the five boroughs — was host to the second-largest Democratic regression in the five boroughs. While Harris bled support with homeowners, her margins in the South American, working-class precincts of North Corona cratered. Hillary Clinton won the 35th Assembly District by sixty-four percent. Eight years later, Kamala Harris won by only thirteen percent.

While not as low-income as neighborhoods like University Heights and East Tremont in the Bronx, the majority of blocks in North Corona are also more than eighty-five percent Hispanic. As noted by Aaron Fernando, many of the most pronounced shifts to the GOP came in precincts adjacent to Roosevelt Avenue, where one local business owner said, “sex work on the thoroughfare, while long a community concern, has become more pervasive in recent years and scares away customers.”

Additionally, the migrant crisis, specifically when tied to fears of crime, resonated across working-class neighborhoods in both Queens and the Bronx. Admittedly one anecdote of hundreds traversing New York City, the author recalls walking down 37th Avenue, one of the main thoroughfares across Jackson Heights and North Corona, this July. Visiting Our Lady of Sorrows, a Roman Catholic Church on 104th Street, whose food pantry and soup kitchen served thousands while the COVID-19 pandemic devastated the neighborhood; the author found fifty parishioners worshiping inside, almost exclusively in Spanish, with the church’s A-frame bulletins sitting outside — with information on upcoming mass times in English and Spanish. However, each A-frame bulletin remained chained, by padlock, to either the wrought iron fence or railing.

Why? Because otherwise, they would be stolen.

Little improved for Kamala Harris in the adjacent Assembly District 39, where she continued to hemorrhage support in overwhelmingly-Latino Corona (south of North Corona), as well as the mixed-South American and working-class, Chinese precincts of Elmhurst. While the gentrifying Jackson Heights historic district did not waver in their commitment to the Democratic nominee, Harris cratered in the Desi (in this case, predominantly Bangladeshi and Asian Indian) election districts which surround Roosevelt Avenue and 74th Street, as well as throughout Woodside’s “Little Manila” Filipino enclave, also home to a growing Bangladeshi community.

Split between Astoria-Ditmars and Jackson Heights, the 34th Assembly District offered a case-study in the collapse of New York City’s Democratic coalition. In the gentrified, millennial-heavy blocks of Astoria (north of the Grand Central Parkway), Harris barely regressed when compared to Joe Biden’s 2020 performance — save for a fifteen point decrease in the last remaining Greek enclave, Astoria Heights. Whereas across election districts in Jackson Heights, Harris saw her vote share decrease between fifteen and twenty-five percent (equaling a 30-50% shift to the GOP). So devastating was Democratic bleeding in Jackson Heights, "the most culturally diverse neighborhood in New York, if not on the planet” according to The New York Times, that Donald Trump flipped several precincts which had not broken for Republicans in the twenty-first century.

Several of these blocks in Jackson Heights and Corona delivered majorities to both Donald Trump and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Each precinct that flipped from Biden to Trump was held by the democratic-socialist Ocasio-Cortez, a clear example of her ability to overperform the top-of-the-ticket in working-class, Latino supermajority neighborhoods — be they Nuyorican blocks in the Bronx, or South American enclaves in Queens.

However, evidenced by both sides of the Queens–Brooklyn border, between working-class Cypress Hills and middle-class Woodhaven, the tale of Latino realignment spanned class. In the former, Kamala Harris ran approximately fifteen points behind Joe Biden. In the latter, the Vice President’s vote share was seventeen points less than the President’s performance four years prior.

Within the decade, Queens is on pace to see several Republican challengers threaten incumbent Democrats in Woodside, Jackson Heights, Corona and Elmhurst.

While each district discussed thus far has witnessed a profound decrease in Democratic support, their overall partisan lean remains blue — albeit a far lighter blue. However, Queens County saw several “Democratic” districts flip to the GOP at the Presidential level for the first time this century, which threatened to imperil multiple incumbents in the State Assembly.

In Eastern Queens, Democratics Ron Kim and Nily Rozic held their seats amidst competitive re-elections while their respective districts flipped from Biden to Trump. In the majority-Asian 40th Assembly District, which includes the working-class, heavily-Chinese neighborhood of Flushing, Kim outran Kamala Harris by thirteen points, while Rozic edged the Democratic nominee by seven-percent in the plurality-Asian 25th Assembly District. Both districts, at the top-of-the-ticket, shifted twenty-five points to the GOP.

The progressive-populist Kim — a consistent critic of the “non-profit industrial complex,” staunch supporter of tenant’s rights, and champion of exploited homecare workers — has remained, in the face of consistent electoral opposition from the right, rather popular amongst the working-poor of downtown Flushing, whose votes insulate him from the more conservative, middle-class homeowners in Linden Hill.

In South Queens, Democrat Stacey Pheffer Amato, after escaping her 2022 bloodbath by a mere 15 votes, trailed early in her rematch with Republican Tom Sullivan. The 23rd Assembly District, once represented by Pheffer Amato’s mother, spans the entirety of the Rockaway peninsula — from the R+50 bungalows of Breezy Point, to the D+60 public housing of Hammels and Edgemere — before snaking up the A train line, along the blood red blocks of Broad Channel and Howard Beach, purple Lindenwood co-ops, and the traditionally-Blue, working-class Ozone Park. While observers posited that Pheffer Amato had already survived the worst-case scenario (Lee Zeldin won her Assembly District by twenty-three percent), and stood to benefit from greater turnout from the district’s Black and Brown residents in a Presidential election year, Pheffer Amato was nearly sunk by a considerable Kamala Harris regression in the Caribbean, Hispanic, and Asian melting pot Ozone Park (where her vote share decreased by eighteen percent). The saving grace for Pheffer Amato, a law-and-order Democrat homegrown in Rockaway Beach, came from the Orthodox Jewish community tucked in the peninsula’s easternmost corner. While delivering eighty-five percent of the vote to Donald Trump, the Orthodox of Far Rockaway split their tickets to great effect, bestowing the Democratic incumbent an identical share, which served as Pheffer Amato’s margin of victory.

While not united by a single Assembly District, some of the largest shifts against the Democratic Party came in the South Asian and Indo-Caribbean neighborhood of Richmond Hill, Queens — against the first Asian-American Presidential nominee no less. Here, countless precincts — home to Sikh Punjabis, Trinadadians, and Guyanese — saw their Democratic vote share decrease by an average of eighteen percent (approximately a 35% swing to the GOP).

However, South Asian realignment — as seen in the handful of Jackson Heights precincts discussed earlier — was not confined to South Queens. The 24th Assembly District, despite its incumbent-protection gerrymander to insulate David Weprin, nonetheless remains the district with the largest South Asian population in New York State. After experiencing a mild shift between Clinton and Biden (ten points to the right), support for Harris collapsed, to the tune of a twenty-eight point shift away from the Democratic Party. Along the election districts of “Little Bangladesh,” adjacent to Hillside Avenue in Briarwood and Jamaica Hills, Kamala Harris underperformed Joe Biden by between fifteen and twenty-seven percent. Throughout the middle-class South Asian corridor of Glen Oaks, Bellerose, and Queens Village, Democratic vote share at the top-of-the-ticket regressed approximately fifteen percent — movement which helped Republican Yiatin Chu come within seven-points of upsetting Democratic incumbent Toby Ann Stavisky in the 11th State Senate District (Joe Biden won the district by thirty-three points). In the small Bangladeshi enclave of City Line, lined with Masjids and Halal grocery stores owed to the neighborhood’s booming Muslim population, Kamala Harris ran behind Joe Biden by greater than twenty-five percent. In one City Line election district, over eleven percent of ballots were write-ins, presumably protest votes against the Biden administration's support of the War in Gaza. In the “Little Yemen” corner of the Van Nest neighborhood in the Bronx, over seven-percent of ballots were write-ins. On the northernmost blocks of Bay Ridge, home to a growing Palestinian community (as well as countless Arab Christian from the Middle East), write-in ballots eclipsed nine-percent of the vote in two election districts. Furthermore, the aforementioned Hillside-corridor enclave of Jamaica Hills had the highest number of write-in ballots of any neighborhood in New York City — with one election district maxing out at seventeen percent.

Overall, twenty New York City Assembly Districts swung to the right by more than thirty-percent since 2016. All of them — save for the Hasidim and Orthodox-heavy 48th Assembly District — were either majority or plurality Latino or Asian.

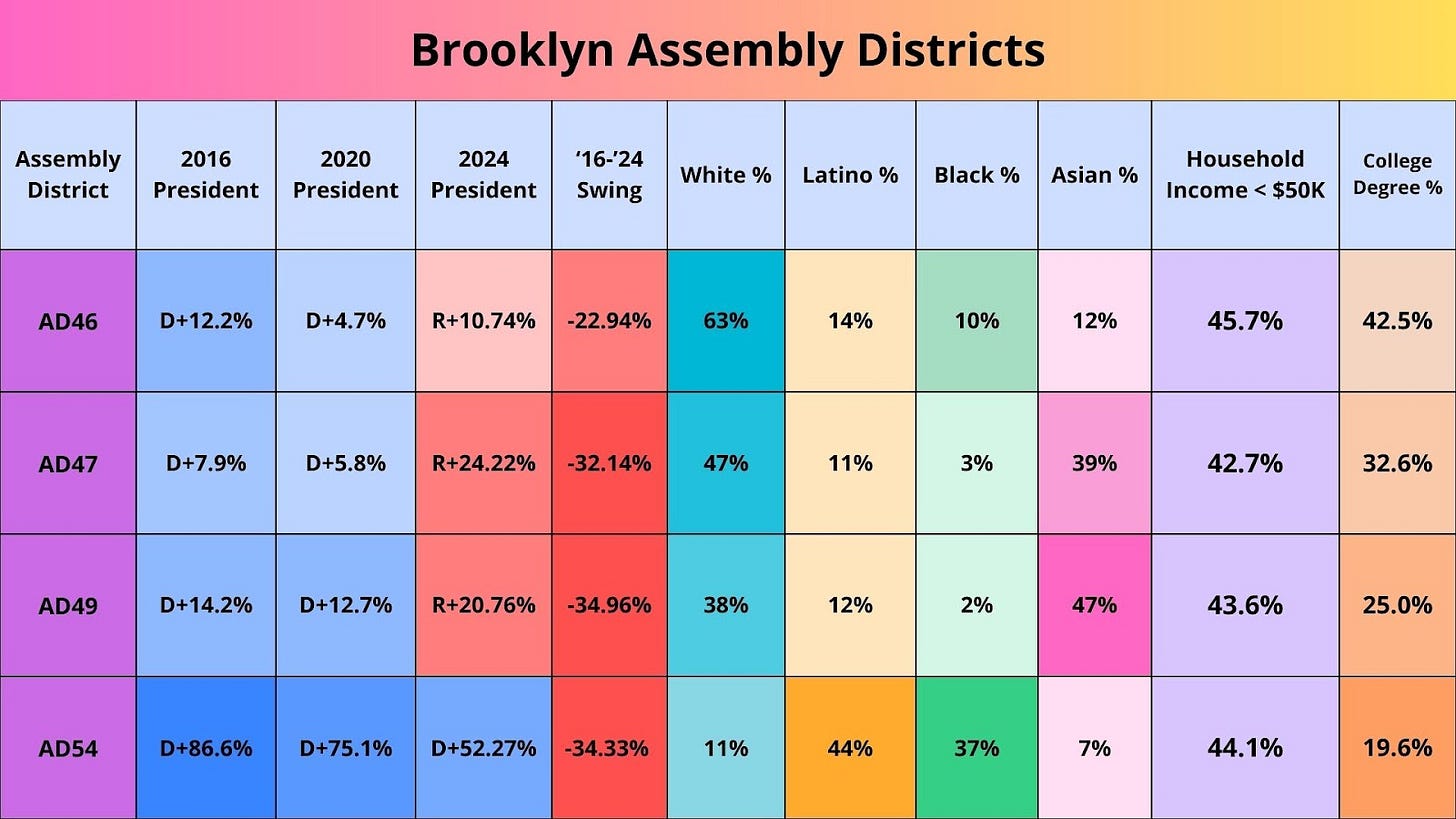

However, the enduring legacy of the 2024 Presidential Election in New York City will be felt in a handful of Southern Brooklyn neighborhoods — won by Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Joe Biden — that, as of Tuesday, flipped decisively to Donald Trump.

AD46 — Bay Ridge, Dyker Heights, Fort Hamilton, Coney Island, Sea Gate

AD47 — Bensonhurst, Bath Beach

AD49 — Sunset Park East, New Utrecht

AD54 — Bushwick, Cypress Hills

Spearheaded by the realignment of the local Chinese population, lackluster campaigns from Eric Adams and Kathy Hochul, consistent voter turnout among more-conservative homeowners, and atrophying Democratic infrastructure which failed to organize growing immigrant communities and effectively assuage their concerns with respect to rising crime — no region of the five boroughs has experienced such a pronounced political shift in the interim between the 2020 and 2024 Presidential elections than this corner of Southern Brooklyn. This current, punctuated by Republican Lee Zeldin’s dominance across the Belt Parkway corridor, culminated in a wipeout of Democratic State Assembly Members two years ago — as Mathylde Frontus (Bay Ridge, Fort Hamilton, Dyker Heights, Coney Island), Peter Abbate (Sunset Park, Bensonhurst), and Steve Cymbrowitz (Gravesend, Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach) were all defeated. Abbate and Cymbrowitz had represented their districts for a combined fifty-eight years.

On Tuesday, Republicans tested their newfound strength against State Senator Iwen Chu, who prevailed by less than six-hundred votes in the newly-drawn, Asian-opportunity 17th District last cycle — which flows southwest from Sunset Park to Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, and Gravesend (with a handful of Kensington, Bay Ridge, and Dyker Heights blocks interspersed throughout). Two years ago, Governor Kathy Hochul lost Chu’s district by thirteen-percent, while Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (an unparalleled electoral titan in New York history, whose political career began in the neighboring legislative district) only bested his anonymous opponent by a meager two-hundred votes. Chu’s survival last cycle, in part, was owed to facing a white opponent, Vito Labella, in a district whose electorate is nearly half-Asian — evidenced by her considerable advantage in the traditionally-Democratic, working-class neighborhood of Sunset Park, where countless Chinese voters along Seventh and Eighth Avenue broke for both Chu, Republican Assemblyman Lester Chang, and Zeldin. While the “red wave” washed over Southern Brooklyn, Chu kept it close in the politically-purple (Clinton/Cuomo/Biden/Sliwa/Zeldin), middle-class neighborhoods of Bensonhurst and Bath Beach — allowing her to eke out a close-victory.

However, her competition this cycle, Stephen Chan, an ex-Marine and former police officer, promised to be far stronger. In many respects, Chan, a former Democrat who left the party “after it was hijacked by the far left, Marxists and socialists,” fit elements of the neighborhood’s political zeitgeist. Nonetheless, Chu’s chances entering Election Day appeared solid, as she was poised to benefit from a considerable party registration advantage — the district has over 68K registered Democrats, approximately 18K Republicans, over 41K voters who are not registered with either party — in addition to resolute support from organized labor.

Nonetheless, the author believed the race would be close, and, intrigued by Chan’s upset potential, spent Election Day criss-crossing the district.

In Sunset Park, a must-win neighborhood for Chu, her Republican opponent was contesting every corner, storefront, and poll site. Posters in opposition to a proposed homeless shelter — four miles away on the border of Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, and Gravesend — lined the streets of Seventh Avenue. Farther south in Bensonhurst; once a predominantly Italian-enclave, now a satellite Chinatown with a declining, but nonetheless politically-active white ethnic population — proved to be the epicenter of Southern Brooklyn’s realignment. While posters in small business windows do not vote, for every one poster for Iwen Chu, there were twenty for Stephen Chan — or as they said, “Chan The Man.” The face of State Assembly Member Bill Colton, a three-decade fixture in the neighborhood, alongside Republicans and Democrats, was ever-present on each block.

Despite his status as a Democrat (and Majority Whip in the State Assembly no less), Colton was seen campaigning alongside Chan at the annual Columbus Day Parade, an event which, unsurprisingly, passes through the heart of Bensonhurst. An oft-overlooked figure, Colton, a conservative Democrat who has served in the legislature for more than a quarter-century, steers one of the last active political clubhouses, the United Progressive Democratic Club, in Southern Brooklyn. With respect to neighborhood politicking: navigating the local institutions and relationships that make-or-break ambitions, particularly in the close-knit residential communities across the outer boroughs — central to prolonged survival in a purple-district — Colton has embedded himself in his community like few others. No ribbon-cutting, ethnic-heritage parade, or civic-association meeting is beneath him. His racially-insensitive comments, like comparing Black Lives Matter to the Ku Klux Klan, draw the ire of institutions like The New York Times (which, despite Colton’s importance to understanding the landscape of city politics, scarcely even mentions the Assemblyman), but lose him scant support inside his district. Ross Barkan described Colton as “the type of politician who will stand on a sweltering subway platform for hours and hand out pieces of paper with his name on it.” When all of his neighboring colleagues in the state legislature were washed away two years ago, Colton coasted to victory by ten points.

No issue this calendar year has proved more salient and inflammatory across Southern Brooklyn than a proposed homeless shelter at the corner of 86th Street and 25th Avenue — which lies beneath the clattering crawl of the D train. The shelter, which would house 150 men, the majority of whom would be Black and Latino, has drawn several large-scale protests – underscoring the neighborhood’s pervasive fears of crime, particularly Anti-Asian hate. Colton, and his protege, City Council Member Susan Zhuang, are the leaders of the anti-shelter movement, which has caught fire across the neighborhood, and beyond. Together, they organize protests — from the early hours of the morning, into the evening — against the shelter. Their volunteers hand out tote bags, in both English and Chinese, directing passersby to sign onto their online petition against the project. In a particularly troubling episode, Zhuang was accused of biting a police officer during one tension-filled demonstration.

If Democrats Bill Colton and Susan Zhuang are the face of the anti-shelter campaign, they did not mind sharing that spotlight with Republican Stephen Chan. While Iwen Chu was also opposed to the shelter, only one of their campaigns was prominently featured at the all-day, anti-shelter protest on Election Day, which doubled as a campaign rally for Chan.

In 2020, Joe Biden won the district by seventeen-percent.

Four years later, Iwen Chu lost by more than ten-percent.

In Dyker Heights, Bensonhurst, Bath Beach – Kamala Harris and Iwen Chu won only one election district (whereas Joe Biden carried each neighborhood). While Chu held her own in working-class Sunset Park, the same could not be said for Kamala Harris, as Donald Trump won several precincts between Seventh and Ninth Avenues – the heart of Brooklyn’s Chinatown.

The election district (AD47, ED44) across the street from the proposed homeless shelter, which firmly supported Joe Biden (454 votes, 59.3%) over Donald Trump (311 votes, 40.3%) according to the CUNY Graduate Center — decisively flipped to Trump (588 votes, 69.2%) over Kamala Harris (262 votes, 30.8%) four years later. Here, where backlash was highest, Iwen Chu (232 votes, 28.1%) fared even worse.

No precinct in all of Brooklyn, the largest county in New York State, moved so far to the right.

Enjoying the piece? Help me reach new audiences by sharing on Twitter !

How will New York City respond to Donald Trump’s return to the White House?

Already, the knives are out. Bronx Congressman Ritchie Torres blamed “the far left” on Twitter, before telling POLITICO that rising costs of living was the real reason. Surrogates of former Governor Andrew Cuomo, eyeing a political comeback, attacked his rival Attorney General Letitia “Tish” James for prosecuting Trump. Zephyr Teachout, integral to building the modern-day political left in New York State, penned an Op-Ed in The Nation stating that Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer should resign.

Here in the five boroughs, the renewed “resistance” to Trump’s return to power will look different than that of eight years prior. For one, many of the local activist groups that emerged following Trump’s first victory are simply no longer active. Secondly, it is worth revisiting the zenith of this grassroots activism, which came in September 2018 when several State Senate insurgents defeated former members of the Independent Democratic Conference (IDC), a renegade group of breakaway Democrats who shared power with Republicans in Albany’s upper chamber.

However, in light of Tuesday, one must ask, for all of the success of the Anti-IDC “resistance” movement during the previous Trump Presidency — where in the five boroughs were those political breakthroughs?

Jeff Klein enjoyed his strongest support in working-class, Bronx neighborhoods like Castle Hill, but could not survive the groundswell of movement against him in upper-middle class Riverdale and Pelham Village, Westchester. Robert Jackson won behind the strength of the Upper West Side and Hudson Heights — Marisol Alcantara was still rather popular throughout the working-class, Dominican-east side of Inwood. North Corona voted to return Jose Peralta to Albany — Astoria, did not. Are you sensing a pattern?

During the previous Trump Presidency, the Democratic base in New York City did expand, culminating in record-breaking Presidential turnout in 2020. However, that rallying and activation was concentrated in upper-middle class and rapidly-gentrifying neighborhoods — while working-class New York drifted farther to the right.

In 2018, liberal Democrats won despite neighborhoods like Castle Hill, Inwood, and North Corona. On Tuesday, Republicans won because of them.

Following Tuesday’s disappointing result, the mass-member organization that is due for considerable growth in membership remains the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America — as was the case during mass-political moments in 2016 and 2020. This development, on the heels of multiple “down” cycles following increased electoral headwinds, comes at a critical juncture, as NYC-DSA is backing the Mayoral campaign of State Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani of Astoria, Queens. While the left has struggled to rally behind a singular movement leader in the post-Bernie era — could Mamdani, amidst a period of political retrenchment, be a municipal-version of Sanders in America’s largest and most influential city?

With that said, the campaign for New York City Mayor has officially begun.

Eric Adams, regardless of the passage of several ballot measures he supported, remains in deep-trouble, amidst rumors of superseding indictments and post-election plans for his removal. Presidential pardon or not — Adams, up for re-election in next June’s Democratic Primary, would still need a miracle to remain in office beyond his current term.

While the Republican electorate is precipitously increasing, it cannot win a citywide election, alone — yet. However, given the dissatisfaction with Democratic municipal government, a current seen across many of the bluest urban centers throughout the United States — which has reached a fever pitch in the five boroughs under the chaotic, corrupt and contemptible administration of Eric Adams — there is an opening, as was the case throughout the 1990’s and mid-2000’s, for relatively-affluent, registered Democrats (while still casting their ballots in even years for the party of Roosevelt, Kennedy and Obama) to support an anti-corruption, tough-on-crime, socially-liberal “Republican” for Mayor. This scenario, not far fetched, would cripple Democratic support in Manhattan, and usher in a changing-of-the-guard in City Hall.

In the more immediate term, the fallout from Tuesday night would have a profound effect on any Special Election — nonpartisan, with ranked-choice voting — for New York City Mayor, which would commence were Governor Kathy Hochul to remove Adams following additional charges. A Special Election would see Republicans and Independents — traditionally shut-out from the de-facto kingmaker: June’s Democratic Primary — many of whom helped Donald Trump reach Ronald Reagan’s numbers in the five boroughs, enfranchised to the fullest-extent. With this bloc capable of swinging the outcome, the majority of Democratic candidates would inevitably position themselves farther to the right.

Despite flipping three House districts on Long Island, the Hudson Valley, and the Syracuse-region — New York Democrats should limit their celebrations, given that the trajectory of Republican gains across the five boroughs could imperil their decades-long control of New York State, sooner rather than later. Since these political inroads came amongst fast-growing immigrant and minority communities, Republicans are on course to organically grow their support in New York City over the next decade.

Demographics are destiny, indeed.

While New York City’s gentrifier class — much-maligned for their left-leaning tendencies in June, staunchly-blue nonetheless come November — continues to swell as the unforgiving housing market cripples working-class neighborhoods; the city’s Black population, a dark-blue reservoir of support that has formed the backbone of the Democratic electorate in every election post-John Lindsay, is fleeing the five boroughs en masse, crushed by suffocating housing and childcare costs. Affluent liberals in Manhattan and Brooklyn’s Brownstone Belt, despite the occasional flirtations with business-friendly, good-government politicians like Michael Bloomberg on the municipal level, have been completely polarized to “the resistance” on the national level amidst the post-Roe, Trump-era. Their future in New York City, while relatively stagnant, remains secure due to their considerable financial flexibility. Together, these three cohorts (one increasing, one declining, one relatively stagnant with respect to population trends) represent the core of the Democratic base in New York City.

Whereas, almost without fail, the ethnic and racial groups where Republican support is increasing, are themselves experiencing considerable population growth, nowhere moreso than in Queens. Latinos are now the second-largest racial group in the five boroughs, and with each passing year, see increased levels of citizenship, voter registration, and political participation. Close to five-percent of New York City is South Asian, with Queens close to fifteen-percent alone, both estimates which have doubled in the past decades. Both Latinos and South Asians, as of now, remain light blue, but have been consistently trended to the right over the past eight years. Furthermore, little is preventing the Chinese electorate, by far the largest percentage of New York City’s fastest-growing demographic group, from shifting even farther to the right. While the Asian realignment crested in Southern Brooklyn — Republicans could conceivably flip Assembly Districts in Flushing and Oakland Gardens over the next decade, in addition to competing for the 11th State Senate District when eighty-five year old Toby Ann Stavisky retires. Furthermore, while the predominantly-Italian (plus Irish, Polish, and Greek) white ethnic population continues to decline, their support for Republicans remains as steadfast as ever. Staten Island, more racially-diverse than ever, delivered a higher percentage of the vote to Donald Trump in 2024, buoyed by the R+55 South Shore, than in either of Ronald Reagan’s landslide victories. So long as their neighborhoods remain exclusively zoned for single-family homes, their political power at the ballot box will endure. These trends cannot be attributed solely to the presence of Donald Trump on the ballot, or the shortcomings of the Kamala Harris campaign at the top-of-the-ticket, given Lee Zeldin nearly replicated the President-elect’s performance two years ago against Kathy Hochul.

Mike Lawler, a Republican Congressman of the Lower Hudson Valley, who handily-defeated Democrat Mondaire Jones en route to a second term in the House of Representatives, is already eyeing the Governor’s Mansion in 2026. Not tied to the election-denialism that compromised Zeldin’s crossover potential, Lawler, who has already demonstrated suburban appeal by winning back-to-back swing district races, will undoubtedly concentrate resources on further-building the GOP in New York City’s outer boroughs. Hochul, already deeply unpopular throughout the state, remains an easy target.

If Republicans can grow their support in New York City to reach forty-percent, they can tip an election for Governor in a midterm year. Consider this — eight years ago, Donald Trump won an all-time low seventeen percent in the five boroughs, the worst performance for a Republican Presidential candidate, in New York City, ever. Now, the GOP has surpassed the critical thirty-percent benchmark in both the past two cycles.

Suddenly, Forty-percent does not feel so far away.

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

This was amazing. Thanks you! In terms of Brooklyn, you kept mentioning the lack of active political clubs. Are you able to speak more to that. When I left the show, Reformand DSA were trying to disrupt the Democratic political machine -- especially the KCDC. But there were more active clubs ( old school and reform) not fewer.. What happened to all the clubs?!!

Best piece I’ve read on the election results for NYC! 🙏 thank you for your thorough and insightful work, hopeful that more people take note 👏