The Rainbow Coalition

The Tale of Two Cities

The cadence of Election Day in New York City is strange and suspenseful.

Before the polls even open, close to one-third of all ballots, steadily acquired during the ten day early voting period, are already in the bank. The data from the “early vote,” released every evening by the Board of Elections, leaves ample time for discernment and dissection. However, when election day voting commences at dawn, there is nothing more than anecdotes, and token borough-by-borough data, for the next sixteen hours. Other states, such as New Jersey and Virginia, periodically provide updates of incoming ballots, based on age, geographic, and party distribution.

New York City does none of that. For election day is shaped entirely in the dark.

I spent last Tuesday following Zohran Mamdani around; mixing in a series of interviews, phone calls, and borough-wide vote total analyses along the way. There was, regrettably, little time to sojourn deep into the outer boroughs. Mamdani opened the day with a playground press conference in Astoria, after voting alongside his wife (and learning, in real time, of Dick Cheney’s passing) at Frank Sinatra High School. The eager crowd of reporters and cameramen, who closed ranks around the Democratic nominee, was comparable to that of a Presidential frontrunner on Super Tuesday. Afterwards, I stopped in a local coffee shop, Sweet Scene, several blocks away and off the beaten path, for a meal and some uninterrupted laptop time. A reporter–photographer duo from The New York Times coincidentally stopped by; laying out their next moves (they planned to visit Ozone Park and speak to South Asian voters). For fun, I scanned The Times archives for references to Ozone Park, a middle-class neighborhood in South Queens, during the previous mayoral race. I only found one, a fleeting reference in the description of a voter interviewed on the street. Now, immigrant enclaves like Ozone Park (and Brighton Beach, Westchester Square, Jamaica Hills) are spotlighted regularly by elite media: The Mamdani Effect in real time. A young woman sat down at my table, opened up her laptop, and dialed into a voter contact software using her cell phone, and was soon calling prospective voters, inquiring as to whether they had already cast their ballots. She was, of course, doing this volunteer work for Zohran Mamdani. Around noon, I set off for Brooklyn, taking the G train (better known as the Commie Corridor express), arriving in Clinton Hill, a brownstone neighborhood with several murals of the Notorious BIG (a native of St. James Place), for Mamdani’s event with State Attorney General Letitia James (that block: Mamdani 84%, Cuomo 14%). At his next stop, on the Lower East Side, voters could barely even reach the Democratic nominee, surrounded by an entourage of allies and media (that block: Mamdani 79%, Cuomo 17%). Pulling away in his SUV security detail, Mamdani rolled down the tinted window and stuck his head out, shouting “BLOCK BY BLOCK baby” at me, a reference to my predictions piece from the day prior. Yelling back, I told Mamdani that I may have undercounted his support once again (“I think you can hit 55%”); in the primary, while I predicted Mamdani would win, one of only a handful to make such a claim, he still outperformed my bullish expectations by twelve points. Mamdani, who has not lost his sense of humor with fame, laughed back, “Don’t be a coward, stick to your prediction!” He was right.

My comment belied a sense of optimism. Mamdani’s best boroughs in the primary, Manhattan and Brooklyn, were once again leading the way in the general. Voter turnout was on pace to easily surpass two million, a figure not reached since the halcyon days of civic engagement during the 1960s. Sure, some of that surge would come from an anti-Mamdani groundswell, most notably a handful of staunchly pro-Israel Jewish neighborhoods, but a higher turnout environment, overall, assuredly benefited the Democratic nominee in a city where Democrats outnumber Republicans 6-to-1. Mamdani still led almost every public poll by double digits, with a coalition — indexed to lower-propensity younger voters and oft-overlooked immigrant groups — that is notoriously difficult to poll. Was another BIG polling miss on the horizon?

As the witching hour arrived, both campaigns hunkered down, playing host to both supporters and the media: Mamdani at Brooklyn Paramount, a theater in Fort Greene; Cuomo at the Ziegfeld ballroom in Midtown Manhattan. In the twentieth century, it would take several hours for the entirety of the citywide vote to be reported, forcing campaign strategists to scrutinize a handful of block-level precincts, bellwethers of sorts, for trends and clues. In 2025, the shape of the results would be known within an hour of the polls closing, as batches of ballots (“drops”) were processed by the Board of Elections; six figure vote totals revealed with the refresh of a webpage every ten minutes. The first “drop” came shortly after 9PM, four minutes after the polls closed, with all 819,165 early votes (in addition to the processed mail-in ballots). As expected, Zohran Mamdani was ahead of Andrew Cuomo: 51.5% to 39.7%. A healthy, but not an “I’ve seen enough,” lead. The pace and distribution of the early vote favors the city’s white collar precincts. Manhattan and Brownstone Brooklyn, walkable and in close proximity to polling sites, are well represented in the early vote tally (advantage Mamdani); in addition to car-dominated, pseudo suburban swaths of Staten Island and Northeast Queens (advantage Cuomo). The precinct results were instantly fed into live maps, painting a political picture of the five boroughs.

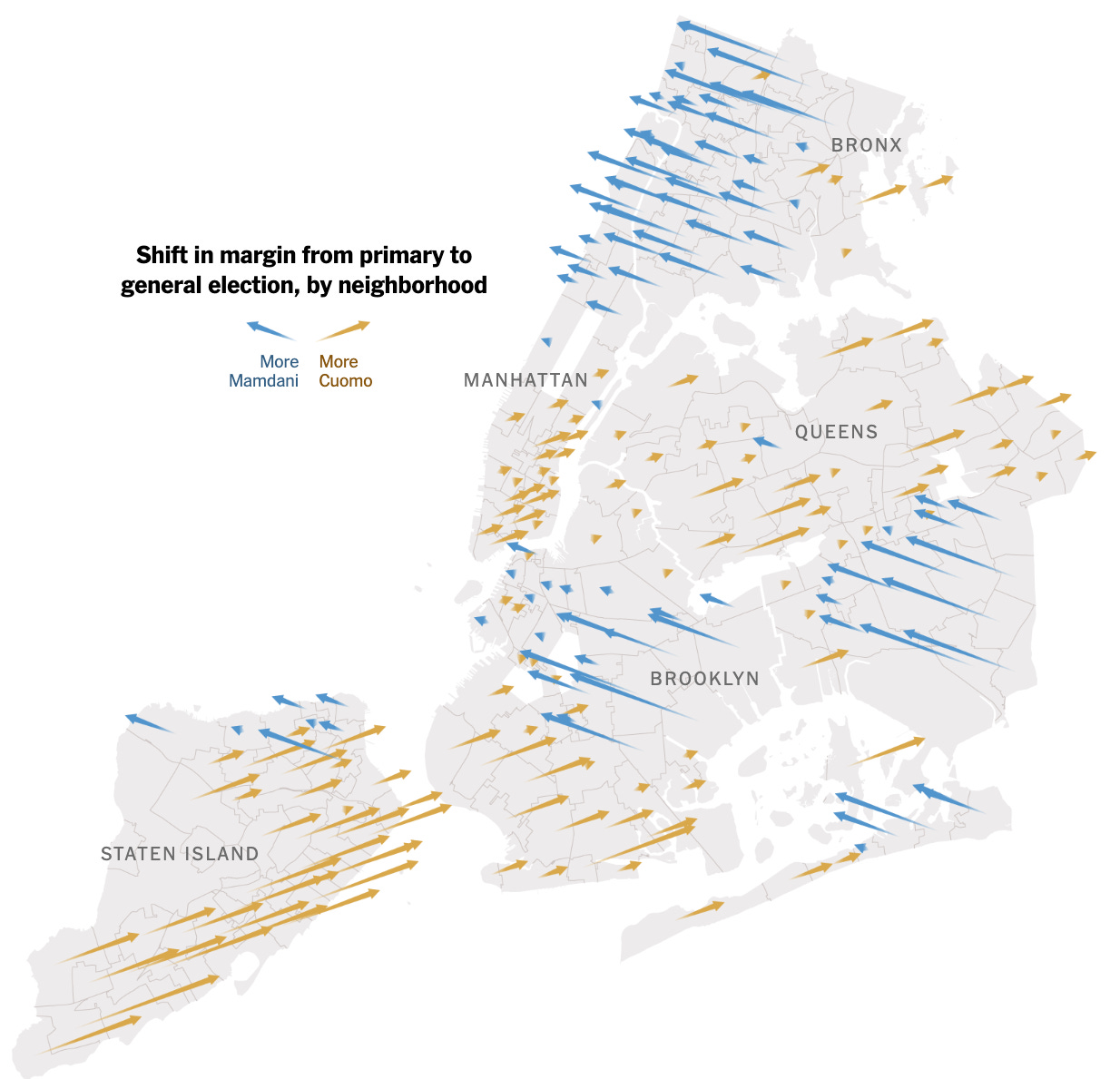

The Commie Corridor could be seen from space, while Upper Manhattan and Central Brooklyn were a sea of Mamdani blue. The working-poor South Bronx and middle-class Southeast Queens — Cuomo Country in the Primary — had swung dramatically to the Democratic nominee. Mamdani’s support neatly traced the city’s subway lines: from the end of the R train in Bay Ridge, to the N/W in Astoria, and the A in Inwood; among the most racially integrated and renter-majority in the five boroughs. Along Hillside Avenue in Queens, the five-mile Bangladeshi, Sikh, and Indo-Carribean thoroughfare where Mamdani began his campaign by speaking to newly-minted Trump voters, the democratic socialist did not lose a single block. Nonetheless, Cuomo held onto a noticeable chunk of the Manhattan vote, anchored by the Upper East Side’s Capitalist Corridor, and the island’s many old moneyed precincts. South of the Staten Island expressway, the most Italian census tracts in the nation, the son of Mario Cuomo was winning every block. The Anti Commie Corridor, pockets of Orthodox and Hasidic enclaves (most notably in Southern Brooklyn) could also be seen from space, supporting the avowedly pro-Israel (and rabidly Islamophobic) Cuomo. There was not a single Republican red precinct on the entire map, for Curtis Sliwa’s support had completely collapsed, the consequence of tactical voting and a late, quasi-endorsement of the former Governor from President Donald Trump.

In mere minutes, as preceding ballot drops were processed by the Board of Elections, Mamdani’s twelve point lead was cut to eight, with more than one million votes still outstanding. Was Zohran Mamdani, who had entered the evening preparing for a coronation, on the precipice of a historic nightmare?

The forthcoming “drops” would be skewed towards the outer boroughs, from the blue collar voters who cast their ballots after work. The small business men and women, the single family homeowner, the union workers, the public school parents: the people the left always claimed to speak for — but could never win. These were the people Cuomo needed to reclaim power, but whose votes he had often taken for granted.

Hours earlier, along Broadway in Upper Manhattan, the Spanish speaking blocks of Washington Heights and West Harlem delivered their votes to the fresh-faced candidate who so eagerly walked their streets greeting passersby months earlier, as Mamdani seldom lost a single block. Inside schools and libraries across Bedford-Stuyvesant, the evening crowd was White and Black, young and old, but united behind the Democratic nominee. Outside IS-145, named after Joseph Pulitzer, in the ethnic polyglot of Jackson Heights, ballots were printed in more than two dozen languages; three-quarters of which were delivered to the candidate who best embodied immigrant New York. Inside the Seth Low Senior Center in Brownsville, at the heart of the city’s lowest income neighborhood, Black seniors bubbled in the oval next to “M-A-M-D-A-N-I,” rather than the name they had known for decades. At Christ Church of Bay Ridge, the local Irish and Italian Catholics that once revered the Cuomo name were few and far between; outnumbered by their Arab Christian neighbors, eager to cast their votes for the inspiring young man who had become a fixture at their houses of worship years earlier. In working-class Westchester Square, where almost forty-percent of voters cast ballots for both Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Donald Trump the previous November, the sounds of Bangla and Spanish could be heard in the gymnasium of Lewis and Clark middle school, a new frontier being unearthed in real time. Uncles and Aunties formed a line at Arthur Ashe School in South Ozone Park, on the precipice of another man of color making history in Queens.

They did so silently and in the dark; their ballots furiously adding up, creating a new political mosaic, piece by piece. And for those who arrived at their polling place still undecided, most were greeted by an enthusiastic Mamdani volunteer, who knew their candidate’s positions by heart, their eager eyes twinkling with the hopes and dreams of the next generation. In those canvassers, many voters saw their neighbors, friends, nieces and nephews, sons or daughters. Perhaps, some even saw a glimpse of earlier, less-disillusioned versions of themselves. Whatever it was, the doors that opened at midnight believed in Zohran Mamdani, and had shut the door on Andrew Cuomo once and for all. The mayor-elect had eclipsed one million votes and fifty-percent.

In short order, Tascha Van Auken, Mamdani’s Field Director and longtime DSA organizer — who strategized, administered, and executed the canvassing plan that made all of those open doors possible — introduced the Mayor-elect on stage.

“My friends,” Zohran Mamdani smiled, “we have toppled a political dynasty.”

I began election day with four questions:

Will Mamdani crack 50%? Yes, with over one million votes.

In total, Zohran Mamdani added over five hundred thousand votes compared to the Democratic Primary. He needed every last one, for Andrew Cuomo doubled his vote total from the Primary, too. But it was from whom Mamdani consolidated support that was remarkable. Amidst voter turnout not seen since the 1960s, Mamdani’s triumph was the result of a coalition rooted in the city’s multi-racial working and middle classes. From the Democratic Primary to the General Election, Mamdani made pronounced inroads with Black (+26) and Hispanic (+22) voters, while cementing his emergent coalition of renters (+25), public transit commuters (+29), younger leftists, older progressives and liberals, South Asians, rent-stabilized tenants, and Muslims (+30). The “Jewish Vote,” much discussed, was far closer than many realize; among Jewish Democrats (precincts where 10%+ of registered voters have Jewish surnames, and Kamala Harris won 60%+ of the vote), Mamdani ran less than two points behind Cuomo (47.8% to 49.2%). Among households earning $30K-$50K, Mamdani won by thirteen points; while households between $50K-$100K went for democratic socialist by twenty percent. Mamdani, of course, won the votes of those who valued a candidate that “would bring needed change” (+62) and “was honest and trustworthy,” (+49) too. Nonetheless, the most instructive Mamdani-Cuomo split was among those in search of a candidate “who will work for someone like me,” a cohort that made up one-fifth of the electorate, and broke decisively for Mamdani by more than fifty points. More than half of voters (55%) said the Cost of Living was the most important issue, dwarfing Crime (22%) and Immigration (9%), more proof Mamdani had actively molded the electorate, rather than merely reacted to it.

This was, unequivocally, the voter coalition the political left had always sought to build.

Can the first major Muslim candidate for mayor win back the city’s working-class Hispanic and Asian communities that swung dramatically towards Donald Trump last November? For the most part, yes, sans struggles with East Asian voters.

The Trump-Mamdani voters are working-class Latinos, South Asians, & Muslims.

And they number in the tens of thousands.

Across neighborhoods like Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Jamaica Hills, Westchester Square, and Glen Oaks — working-class, immigrant enclaves — Zohran Mamdani outperformed Kamala Harris in vote share (and, some cases, raw votes), despite facing another Democrat (running as an Independent) and a Republican. Here, the man who relentlessly focused on costs of living, listened to the plight of immigrant New York (hosting press conferences with night workers, speaking to former Trump voters), all while showing up – over and over again — delivered on his promise. The sole weak spot: East Asian voters (mostly Chinese). The caveat is class and age.

In working-class Elmhurst, one of two Chinatowns in Queens, Mamdani easily outpaced Cuomo by fifteen points (a comparable margin to the Democratic Primary). Throughout downtown Flushing, a lower-income Chinatown at the conclusion of the #7 train, Mamdani and Cuomo split a handful of precincts. But, in the adjacent and more middle-class Murray Hill (Queens), Cuomo outran Mamdani by double digits. In neighboring Bayside, home to the Korean middle-class, Cuomo won by twenty five percent. In Southern Brooklyn, the emerging Chinese communities of Bensonhurst, Bath Beach, and Gravesend contributed relatively few votes during the Democratic Primary (in June, Mamdani clobbered the listless Cuomo there, aided by younger, second generation immigrants). However, these middle-class neighborhoods have become the epicenter of rightward political realignment over the past five years. And last Tuesday, the behavior of these voters mirrored that of other Republicans: abandoning Curtis Sliwa en masse, and shifting dramatically towards Andrew Cuomo. Why? A series of damaging headlines (“Mamdani Says He Would Phase Out Gifted Program”) from both The New York Times and New York Post, articles which received tens of millions of impressions, surely did the Democratic nominee no favors. Nor did Cuomo’s repeated attempts to tie Mamdani to the legalizing (and proliferation) of prostitution, a damaging charge in middle-class immigrant enclaves. Nonetheless, the result goes well beyond just Mamdani, and should be contextualized in the multi-cycle realignment of Chinese voters away from the Democratic Party.

How many Republican voters can Andrew Cuomo peel away from GOP nominee Curtis Sliwa? A hell of a lot, Sliwa didn’t win a single precinct.

Andrew Cuomo tried a reverse Dan Osborn — let me explain.

Osborn, an Independent candidate for Senate in blood red Nebraska, benefited from the Democratic Party eschewing the race entirely; allowing the mechanic to consolidate support from the state’s Democratic voters, while making an anti-oligarch play for Independent and Republican voters, leading to the greatest over-performance of any Senate candidate in the nation. In deep-blue New York City, particularly amidst Donald Trump’s second term, the Republican Party is equally toxic. While Cuomo, a lifelong Democrat running as an Independent, marginalized Curtis Sliwa to a remarkable extent, had the Republican nominee actually quit the race (or eschewed it entirely), the outcome may have been different.

Given the tactical voting exhibited by New York Republicans, could a similar (more coordinated) strategy work against progressive and socialist Democratic nominees at the city and state level? The Reverse Osborn: the GOP stands down and rallies behind a centrist “Democrat” embraced by the billionaire class, who runs-up-the-score among suburban moderates, Orthodox and Hasidic Jews, and white ethnics, while retaining some appeal among non-white working-class voters. Yet, Andrew Cuomo, a scandal-scarred candidate who ran consecutive listless campaigns, still retained an ability to thread an (otherwise) unaligned coalition; his electoral appeal (Cuomo once routinely exceeded 80% of the vote in NYC), while diminished, is still unique.

Would the New York GOP be wise to re-create this strategy?

Will the Black electorate, older and historically loyal to Cuomo, shift to Mamdani, the Democratic nominee? Yes, providing his margin of victory.

In my opinion, this is the story of the election.

Zohran Mamdani’s inroads with Black voters were not pre-ordained, nor the sole consequence of him being the Democratic nominee. For nine months, Mamdani has been double (and triple) booked with church services every Sunday, hustling between Harlem, Southeast Queens, and Brooklyn’s Black Belt. But since the primary, the African-born Mamdani gained relationships and institutional validators across the Black community by the day, allowing him unfettered access to larger congregations and wider audiences. During the Primary, Mamdani’s allies attempted to host a rally at the legendary Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, only for the well-connected Cuomo to call in a favor and nix the effort; but as the Democratic nominee for mayor, Mamdani was able to speak at Abyssinian on the eve of Election Day, seated alongside Harlem’s political class. From the pulpit, Mamdani would tell the story of his father’s Civil Rights era activism, a “which side are you on” moment for the young academic, while making light of the pronunciation of his name to lighten the mood, an old trick employed by early career Barack Obama. Over the course of weeks and months, these efforts made a difference, undoubtedly hastened by Cuomo entering a de-facto truce with Donald Trump in an effort to court Republican voters.

Zohran Mamdani built the next chapter of New York City’s Rainbow Coalition.

Coined by Jesse Jackson during his consecutive Presidential campaigns, the Rainbow Coalition (locally) is most commonly associated with the triumph of David Dinkins in 1989. At a tense, sliding doors moment in the city’s history (well-chronicled in Jonathan Mahler’s The Gods of New York), the soft spoken Dinkins, one of Harlem’s legendary “Gang of Four,” brought together upper-middle class Jewish liberals, labor unions, and the city’s large (but oft-ignored) working-class Black and Puerto Rican communities. An enthusiastic majority of New Yorkers helped Dinkins defeat both three-term incumbent Ed Koch and the (white) backlash campaign of prosecutor Rudy Giuliani. The Rainbow Coalition was beautiful and robust, but amidst zealous and alert opposition, its margin for error was slim. Under the weight of record-breaking crime, complicated by the specter of race and class in a segregated and economically-divided municipality, the “Rainbow Coalition” buckled. When Dinkins and Giuliani rematched, New York City’s first Black mayor lost by less than 2%.

While New York City has changed remarkably over the following three decades, there are many parallels to the present moment. The opposition to Mamdani, while not a majority of the city, is fierce and well-represented throughout elite institutions. There will be no “benefit of the doubt” for the thirty-four year old mayor, nor a plethora of second or third chances. Mamdani will deal with a hostile federal government, as large swaths of his Party openly root for his failure. His ambitious agenda will be, to an extent, at the mercy of his (soon to be former) colleagues in Albany. In the words of NYC-DSA co-chair Gustavo Gordillo, “the fate of the organized left and the Mamdani administration will be tied together.” In the story of David Dinkins and his failed re-election, Zohran Mamdani has a cautionary tale of backlash politics.

Nonetheless, the eleventh-hour rally to Andrew Cuomo felt like the last gasp of the Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg coalition, arrangements that once reigned municipal politics. The core tenants of Mamdani’s coalition are the city’s most ascendant demographics: young voters, the college-educated renter class, South Asians, and Muslims. While he made pronounced inroads among working-class Black and Hispanic voters the past four months, his ceiling for improvement is even greater. The intelligentsia of Manhattan may sour on him, or rally behind a white-collar adversary in four years, but Mamdani will almost assuredly deepen his reservoir of support across the blue-collar outer boroughs; net positive arithmetic in the equation of re-election. His ability to command attention and comprehensive understanding of new media gives him a unique, and unparalleled, ability to disseminate his message.

Most importantly, Mamdani has a political movement at his back. One could quantify that movement as more than one hundred thousand volunteers, more than one million votes, or more than three million doors knocked. But a movement should not be quantified, for the will to climb a sixth floor walkup in search of conversation cannot be reduced to numbers on a screen. A movement must be nurtured and protected, but also given space to grow organically. Movements need leaders, and Mamdani has become that, and so much more. Already, the mayor-elect appears poised to not re-create the failures of Obama’s own vanished volunteer army. Since Mamdani stepped off the R train in Bay Ridge, in search of Father Khader El-Yateem eight years ago, he has never stopped organizing. He will not only bring that ethos to City Hall, but foreground it in the next generation of New Yorkers who have been inspired by his rise.

To these folks, Zohran Mamdani represents hope. And you can’t put a price on that.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Another excellent piece, Michael. Just wanted to respectfully make one historical correction, in service of your overall narrative: while Jesse Jackson made "Rainbow Coalition" a household name, credit for coining it truly belongs to someone who named the original coalition from the late 60s that bears its name. That formation, led by Fred Hampton and Bob Lee, brought together BPP, Young Lords, and Young Patriots, and its name was appropriated by Jesse Jackson for his own subsequent coalition. Given the socialistic politics of both leaders in the original RC and leading forces in Zohran's electoral coalition, I find the true origin of the name to provide an even more satisfying through-line to the present.

Like you, I was surprised that Zohran didn’t win by more. I didn’t expect white outerborough support to surge like it did. But it seems like Cuomo’s negative campaign helped mobilize a reactionary electorate based on nativism.

There were many writing off the Bronx after Cuomo won the primary. Zohran consolidating union and local political support helped boost the working class black and latino vote. These voters are not as driven by ideology as much as they are about supporting the candidate who has adjacent institutional support. It’s what helped Eric Adams in the last primary.