New York City’s Seaside Swing State

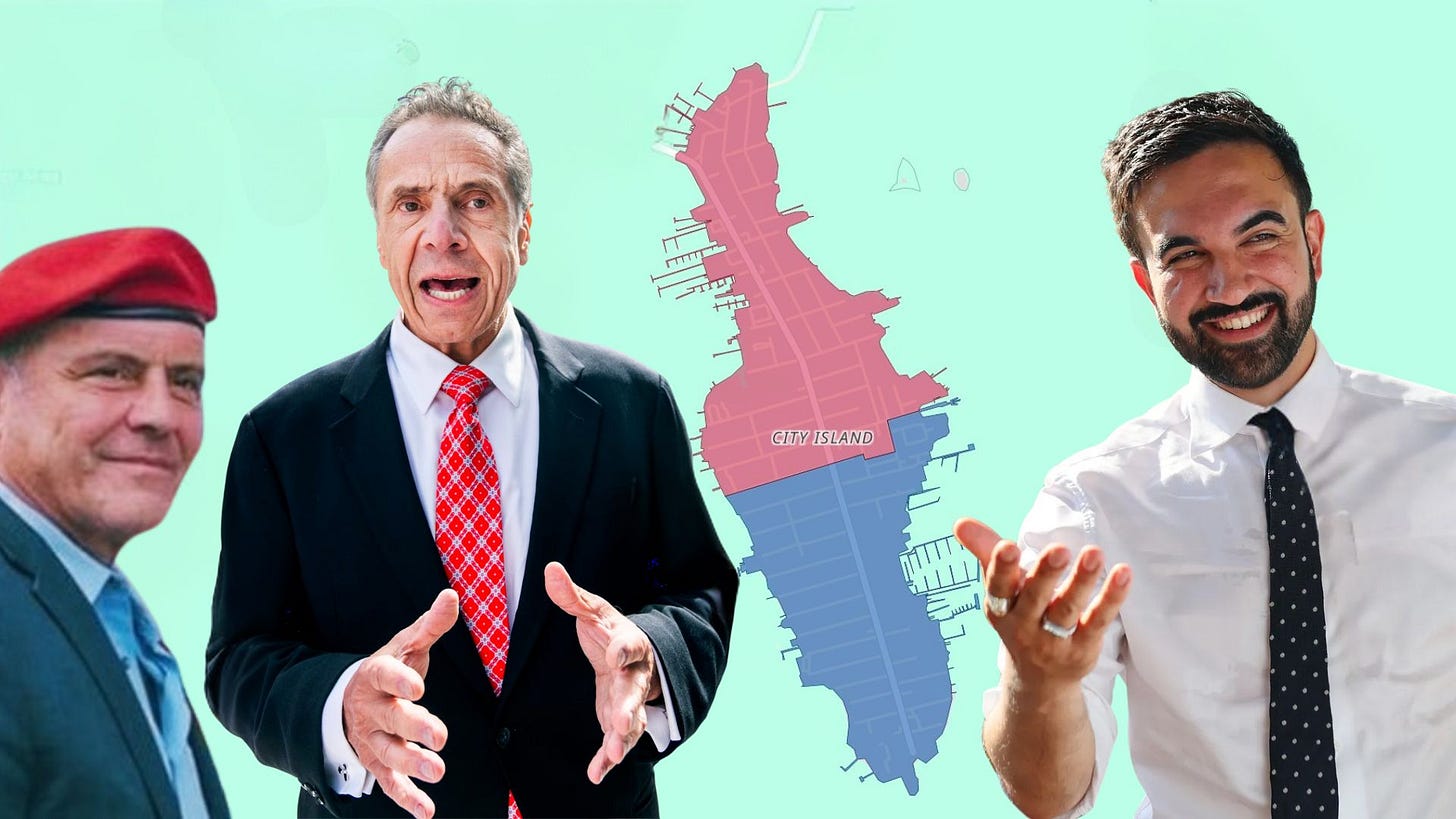

No Democrat running for Mayor has won City Island in 40 years. Can Zohran Mamdani change that?

In 1895, the seafaring residents of City Island — a quiet, Bronx neighborhood adrift Eastchester Bay and the Long Island Sound — were presented with a choice: remain in Westchester County, or join New York City.

With 900 ballots cast, New York City defeated Westchester County by two votes. In exchange, City Island received a bridge to the mainland.

Even one-hundred and thirty years ago, City Island was a swing state.

Hailed as a “working man’s Nantucket” by The New York Times or the “Bronx Hamptons” in the eyes of Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, City Island is one of the only neighborhoods in New York City where one can spot Black Lives Matter and Thin Blue Line flags on the same street. Last November, single family detached homes alternated lawn signs in support of Kamala Harris and Donald Trump; with the Democratic nominee ultimately prevailing: 1,138 votes to 990.

While trending left at the national level (Gore, Kerry, Obama, Clinton, and Biden all won), the Island consistently leans right at the local level. In fact, no Democrat candidate for Mayor has won City Island in forty years. Inside an Irish watering hole at the heart of the Island’s “downtown,” two women, both registered Democrats, lament the “crapshoot” of choices on November’s ballot: Democratic nominee Zohran Mamdani, Independent candidate Andrew Cuomo, and Republican Curtis Sliwa.

“I want Michael Bloomberg back,” says one. “I loved Rudy Giuliani, but now he’s a kook,” replies the other. Both loathe Donald Trump, plan to vote for Kristy Marmorato (the area’s Republican Council Member), but are undecided on the Mayoral race: “I’ll know when I walk into the booth,” a familiar sentiment heard across the Island.

And that is exactly why I ventured to this seaside village in the Bronx. In the majority of New York City’s 365 neighborhoods, one candidate (maybe two) will be competitive this November, owed to partisanship and demographics. City Island, with a unique and diverse political culture (home to civil servants, resistance liberals, Archie Bunker boomers, and everything in between), remains the exception: possessing discernible pockets of support for Mamdani, Cuomo, and Sliwa.

Despite this eclectic tapestry, there is little scholarship about City Island, much less its fascinating politics, reducing the Island’s footprint to a handful of articles (primarily real estate focused). Here, I hope to change that.

“This is a place, after all, where tumbledown bungalows, tall Victorians and squat brick duplexes may share a street with ordinary capes and colonials. A place where a drab insurance office, a colonial church and a rusting junkyard are neighbors.”

From an early age, civic engagement is fostered across City Island, bred by the burning desire to “protect” the Island’s fragile character — from crime, summer traffic, environmental catastrophe, or runaway development.

For generations of Islanders, guarding against the latter has been a time-tested tradition, the roots of which can be traced back centuries. Dating back to 1761, City Island has been targeted for development. August Belmont, a political insider who founded the Belmont Stakes, “quietly” tried to buy up the Island’s precious real estate, intrigued by the possibility of developing a horse racing center. When the Islanders became privy to Belmont’s intentions, they came together to keep prices out of the financier’s vast reach, ultimately thwarting his effort. Nor would it be the last time Islanders organized to preserve their nautical colony, as the preceding centuries saw “exclusive resorts, enclaves for wealthy yachtsmen, and an amusement park” attempt to establish a foothold on the Island, only to suffer similar fates. City Island’s first apartment complex, the rent-controlled Pickwick Terrace, was built in 1964, totalling all of seven stories. A decade later, height restrictions were imposed capping future development at three stories. Low density is prized, and rezonings are unwelcome.

A coastal community, to say the least, climate resilience and conservation are far from theoretical to Islanders. Runoff from the Hutchinson River has polluted the surrounding channels, threatening the long-term health of those who grew up swimming in said waterways. Memories of Hurricane Sandy endure, while an ominous billboard looms — depicting waves crashing onto City Island in the year 2050, foreshadowing the next generation of flooding — at the heart of the main thoroughfare. Several organizations, including City Island Rising and the Oyster Project, have spawned to protect this precarious ecosystem.

This creates an interesting bi-partisan dynamic, where the Island’s political left, right, and center are relatively united against development (historically conservative), but also care about climate resilience (traditionally liberal). John Doyle, an outspoken Democratic District Leader, attributed these non-partisan attitudes, in an era defined by polarization, to the Island’s community-oriented ethos: “It doesn’t matter if you’re a D or R, when the floods come we’re all F’d.” However, the past decade has surfaced underlying tensions among this close-knit neighborhood. At the Irish pub, the liberal Democrats (bespectacled women) gravitated to one side, while the MAGA-aligned Republicans (gruff older men) drifted to the other. When Republican politicians visit the Island, they often frequent City Island Diner; whereas Democratic candidates opt for Clipper Coffee. “When I was growing up,” a Catholic Democrat and thirty year resident told me, “no one would even ask you who you voted for, it just was not polite.”

“City Island is the New Hampshire of the Bronx”

During the twentieth century, what was once a blue-collar fishing village, where residents lived and worked on the Island, gradually became a residential community with “far more people in professional and managerial jobs than in craft and repair operations.” City Islanders have always rejoiced in their relative anonymity, which had helped keep their precious sanctuary affordable. The slow erosion of the local maritime economy, coupled with the steady outmigration of Italians, Irish, and Germans from other Bronx neighborhoods (fueled by white flight in the 60s and the fiscal crisis in the 70s), lifted the veil of secrecy that once shielded City Island from the speculative outside world. Today, less than ten-percent of residents work on the Island, almost exclusively in the small businesses that line City Island Avenue.

This arc mirrors a political transition. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried for a fourth term versus New York Governor Thomas Dewey, the architect of the New Deal won 61% in New York City; but amongst the white working-class shipbuilders of City Island, his Republican opponent took more than two-thirds of the vote (some Italians resented FDR for going to war with fascist Italy). Patriotism and patriarchy are integral to the identity of the Island’s white ethnic families. The American flag is omnipresent on City Island: a staple of every front yard, an homage to achieving the middle-class dream of homeownership, and a reminder of the generations of Islanders who were raised in the shadow of the second World War.

After World War II, City Island remained a GOP stronghold for decades, delivering majorities to Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush. The wartime economy of ship building steadily declined; when the final boatyard closed in 1982, gated condominiums, fittingly named The Boatyard, were swiftly built atop the remnants, embodying the Island’s economic transition. On the municipal level, the Republican Party prevailed as well. Sixty years ago, liberal Republican John Lindsay narrowly won City Island, while William F. Buckley, the architect of modern conservatism, finished a close second. Four years later, after Lindsay’s liberalism was rejected by the GOP faithful, much of the blue collar Bronx, in closer proximity to racial encroachment, backed conservative Democrat Mario Procaccino, the candidate whose rhetoric, inflammatory and apocalyptic, matched their own emotion. City Islanders, sequestered from the anxiety of the mainland, delivered a plurality of their votes to the patrician John Marchi, the soft spoken Republican nominee from Staten Island. These party trend lines held through the late 80s, with notable and instructive exceptions for Italian-American Democrats, such as Mario Biaggi and Mario Cuomo. “I loved Mario Cuomo and wanted him on the Supreme Court,” said a late Gen-X Democrat and Muscle Sucker (the colloquial name given to those who move to City Island; Clam Diggers are born on the Island).

“I wish his son was more like him. Mario was a very compassionate human being.”

As City Island became more of a “bedroom community” and the Democratic Party embraced neoliberalism, the national trends shifted. Since 1992, every Democratic candidate for President has won City Island, a remarkable reversal after generations of consistent Republican support dating back to the Great Depression. Over the last decade, as the Hispanic and Asian working-class of the five boroughs have shifted dramatically to the right, City Island remained one of a handful of neighborhoods to move to the left, mirroring upper middle-class and suburban shifts across the country.

Nonetheless, City Island maintained its red hue on the municipal level, delivering substantial mandates to Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg in six consecutive elections. Even when Bill de Blasio consecutively won 73% and 66% of the citywide vote, the Park Slope Democrat failed to win a plurality on City Island. No Democratic candidate for Mayor has won City Island since Ed Koch in 1985. To this day, when politics is mentioned, many yearn for Giuliani and Bloomberg. Even as the national environment has become more polarized, City Islanders have continued to split their tickets in local, state, and federal elections; when Joe Biden beat Donald Trump by fifteen percent, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez lost to Island-native John Cummings down the ballot. In this seaside village of no more than forty-five hundred residents, the quality and longevity of one’s relationships can transcend political ideology.

“City Island is the New Hampshire of the Bronx,” Doyle tells me, “people here like to get a feel for the candidates.” Four years ago, several mayoral candidates visited City Island, including second-place finisher Kathryn Garcia, who ultimately won seventy-five percent of the Island’s voters (the technocratic Garcia is closer to the Island’s ideological median than anyone in the current field). Those closely involved in City Island politics, both Democrat and Republican, cannot recall an instance when Andrew Cuomo has ever visited their nautical colony. In fact, the only major candidate for mayor to visit City Island this cycle has been Zohran Mamdani.

In March, Mamdani cut one of his signature videos, visiting a handful of small businesses: Clipper’s Coffee, Cinema on the Sound, and Dan’s Parents House (a phenomenal toy store). “That was the most views on social media we have ever received,” the owner of both the coffee shop and cinema where Mamdani appeared, told me. The cinema, in particular, (one of only three in the Bronx) received an uptick in business following Mamdani’s video, which received more than half-a-million views. Mamdani was unknown when he first made landfall on City Island, but his video quickly made the rounds to residents. In June’s Democratic Primary, the well-known Cuomo barely edged Mamdani — 52% to 48% — across the Island.

“I liked his answer in the debate, when they asked each candidate where they would visit as mayor,” a Millennial Democrat told me, “and he said ‘I’m going to stay in New York City.’” The man continued, “It was refreshing to hear that. Our City Council Member just came back from a trip to Israel. She represents Throggs Neck, Country Club and Pelham Bay — why is she visiting Israel?”

In many respects, Mamdani represents a new era of City Island politics, brewing since Donald Trump was first elected. Unlike other “swing state” neighborhoods in New York City, the Democratic electorate on City Island is relatively liberal, a consequence of generation. The inflection point came in 2018, when progressive Alessandra Biaggi challenged State Senate incumbent Jeff Klein, who brokered a controversial power sharing agreement with Republicans in the state legislature. Local Democrats, rallied by the neighborhood’s Indivisible chapter, put off by Klein’s ties to the GOP, and catalyzed by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s victory months earlier, helped deliver City Island to the progressive insurgent by a two-to-one margin. Many of the older Italian voters, erstwhile loyal to Klein, their ethnic brethren, had left the Democratic Party.

Alessandra’s grandfather, Mario Biaggi, was beloved on City Island during his two decades in Congress. A decorated former police officer who was shot eleven times in the line of duty, the tough-talking Mario was a fixture of the East Bronx, running on the Democrat, Republican, and Conservative Party ballot lines. “A law-and-order conservative who supported labor, Israel and laws to crack down on drugs, lift local businesses, and help families and the elderly,” Biaggi embodied the spirit of his Italian and Irish working-class constituents. When forced to resign from the House of Representatives following multiple felony convictions for corruption, Biaggi remained on the ballot in both the Primary and General Election. Declining to campaign altogether, the disgraced Biaggi was handily defeated. However, the ex-cop still won City Island, in both the Primary and the General Election, whose loyal residents still held a four-hundred person rally for the scandal-scarred icon on the eve of the vote.

If Mario understood the zeitgeist of City Island’s old guard, law-and-order conservatives relentlessly focused on local concerns; Alessandra embodied the next generation, unabashedly liberal in an era shaped by national politics.

City Island remains rich in union density — nurses, carpenters, teachers — traditional hallmarks of the Democratic electorate, the vast majority of whose leadership has endorsed Mamdani. On the big development question of the day, whether or not to add a NYC Ferry stop to the Island, Mamdani is supportive, as is much of the local business community and the younger, white-collar professionals who work in Manhattan. Once greater than 95% white, the City Island of today is more racially diverse than ever. While Italian delicatessens and Irish pubs can still be found, one will not have to venture far to find a landmark of Bronx life, the Puerto Rican flag. Latinos — once relegated to visiting the Island during crowded weekends or working the handful of restaurant, landscaping, or boatyard jobs available year-round — now account for one-quarter of City Island’s population, whose votes Mamdani won by double-digits in the Primary. Pride flags are commonplace in small businesses and front yards. There is even a quasi-hipster coffee shop and a yoga studio. The shared values of Islanders — inherent skepticism of real estate development (and those who take their campaign contributions), firsthand concern with respect to climate change, and embrace of public education (PS 175 is one of the best rated K-8 schools in the Bronx) — align with key issues championed by progressives like Mamdani.

Nonetheless, the tide has not turned definitively in Mamdani’s favor. Familiar skepticism (“how will he pay for that?”) is common among older Democrats (“he’s making promises he can’t keep”), while Republicans shudder, afraid the property taxes on their semi-detached homes will be increased (“he wants to raise taxes only in white neighborhoods”). City Island is home to a small but engaged Jewish population, many of whom worship at Temple Beth El (one of the only Bronx synagogues outside of Riverdale). According to Ryan Grim’s reporting in The Squad, after Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez voted against funding the Iron Dome, “rabbis from City Island who were typically progressive and on her side were sending out mass emails warning that her vote would put people’s lives at risk. She had even been banned from attending High Holidays in her district.” Years later, as tensions with respect to Israel and Palestine have risen precipitously, one can assume the folks who organized against Ocasio-Cortez did not vote for the anti-zionist Mamdani in June. Nor have Mamdani’s past statements in favor of “defunding” the police helped in a community home to hundreds of retired police officers. As Mamdani-mania grips the nation, many City Islanders, highly informed and politically savvy, still don’t know what to make of the man who has captured America’s attention. “He seems sincere,” one woman, 64, tells me, gesturing towards a television broadcast of News 12 The Bronx, showing Mamdani and Governor Kathy Hochul speaking at a press conference. “You never know whether what they’re saying about him is just fear mongering,” she admits. But, in the quest to win the hearts and minds of City Islanders, Zohran Mamdani’s stiffest competition may not come from fellow Democrat (turned Independent) Andrew Cuomo, but Republican Curtis Sliwa.

In the eyes of the GOP faithful, Sliwa has been a staple of the East Bronx, the borough’s only Republican outpost, for years. Before the infamous “Hochulmander” map was overturned by the courts, he weighed a move to the Bronx to run for Congress. Four years ago, Sliwa won 50% of the City Island vote as the Republican nominee, finishing five points ahead of Eric Adams, albeit in a very low turnout General Election. And, despite Republicans only accounting for 24% of the Island’s registered voters, Donald Trump’s consistent 45%+ performance on City Island indicates that Curtis Sliwa has the highest floor of any candidate. Andrew Cuomo has attempted to court Republican voters, casting Sliwa as a hopeless spoiler, in the hope of coalescing the anti-Mamdani electorate; according to the latest Quinnipiac University poll, Cuomo is winning 37% of Republicans, compared to Sliwa’s 54%. If City Island is any bellwether, that plan remains flawed, if not doomed entirely. For among City Island’s Republicans, appetite for Cuomo is scant. “He’s not a predator, but he’s a sleezeball” grumbled one Italian Boomer, a GOP loyalist. Another spent months in a nursing home during the pandemic, and swore off Cuomo then and there. Frank Ramftl, the Republican District Leader, told me he is sticking by Sliwa, and his Republican neighbors are doing the same: “Cuomo got us into this mess, he signed the bail reform laws.” His Democratic counterpart, Doyle told me, “40% of City Island is MAGA; unless there is a personal appeal from Trump on Cuomo’s behalf, those folks will vote for Sliwa.” Sliwa has raised more money, from more donors, on City Island than both Mamdani and Cuomo combined. Even among Trump-hating Democrats, opinions of Sliwa were mixed. “He cleaned up the subway,” one woman told me, referencing his founding of the Guardian Angels, while another dismissed the political gadfly and his signature red-beret: “Sliwa is not a governing person.”

Herein reveals Andrew Cuomo’s best chance. Many Democrats — liberals, moderates, conservatives — tell me they “liked Cuomo as Governor,” fondly remember his daily briefings during the pandemic, and voted for him in the Primary. Indeed, when voters are asked who has the “right kind of experience to be mayor,” Cuomo enjoys a wide lead over Mamdani: 72% to 39%. Homeowners, two-thirds of City Island’s electorate, are a constituency theoretically ripe for Mario’s son. Cuomo’s problem, as it has been the entire campaign, is generation. City Island is older than New York City as a whole (over 70% of the Democratic electorate is over-50), yet Cuomo barely beat Mamdani in the Primary; before a tidal wave of press coverage increased the Democratic nominee’s name recognition. If Andrew Cuomo falls short on November 4th, as polling suggests, it will be because the former Governor, running without a Party, found himself boxed out for votes — by the Democratic Mamdani and Republican Sliwa — in neighborhoods like City Island.

For several decades, every warm weekend has been met with hundreds of Bronxites toiling across the borough to experience, albeit for a fleeting afternoon, the spoils of City Island: a taste of fried seafood at Sammy’s Fish Box, the summer breeze off the Long Island Sound, capped off by a breathtaking view of the Manhattan skyline beyond the Throgs Neck Bridge. Making their pilgrimage from Morrisania, University Heights, Parkchester, or Soundview, these visitors – largely the borough’s Black, Puerto Rican, and Dominican urban dwellers — see the Island as a nautical reprieve of blue and green within reach of working-class families used to a life of asphalt and concrete. This “patchwork of race and class” is where City Island “begins to look more like New York than anything resembling Martha’s Vineyard.” While the weekend influx elicits predictable complaints from locals about traffic and noise – such grievances are limited to just that. Indeed, countless small businesses on City Island, the few remaining on a commercial strip still recovering from the economic crash of 2008, are sustained by Black and Hispanic patrons. Spending their teenage summers in restaurant work at Johnny’s Reef or Seafood City, generations of Islanders are acquainted with their fellow Bronxites on the warm Saturday afternoons of Spring and Summer. This acquaintance — between those intimately aware of the precarity pulsing through the concrete jungle, and those whose understanding is confined to the secondhand — however fleeting, nonetheless fosters a degree of respect and acceptance often denied in more segregated enclaves.

“One thing summer weekends do is to dispel the myth that Blacks and Puerto Ricans aren’t family men, says one City Islander. ‘In the worst heat there’s a double line of cars, backed up all the way off the Island, with 15 kids and a mother‐in‐law in the back seat, coming to get mediocre food at outrageous prices. Any one of them is certainly more of a family man than I could ever be.” (The New York Times)

This ethos sets City Island apart from other neighborhoods in the East Bronx. Infamously, many of the communities across the bay — Country Club, Edgewater Park, and Silver Beach — which share a racial, class, and ethnic profile similar to City Island, have conspired to keep people of color from buying homes in their sequestered enclaves.

Whereas the key to City Island’s culture is rooted in proximity to people different from oneself. For when I strolled through the streets of this authentic coastal hamlet, there were fewer political lawn signs than I observed one year ago. What I did see was friends and family who knew one another on a first name basis, almost every house eagerly preparing for Halloween, and small acts of mutual respect between neighbors.

Because after November 4th, City Island, split between Zohran Mamdani, Andrew Cuomo, and Curtis Sliwa, will continue to co-exist — as it always has.

Perhaps the rest of us could learn something.

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

NY is a city of villages scattered across the five boroughs, from Canarsie to Stuy Town, enclaves where we have wed and raised our families. I have a nodding acquantanceship with the corner food cart, the waitress in the corner diner, my pharmacist, my dry cleaner ... its why I love NY, never thought about fleeing to Florida ... my neighbors range from loathing Mamdani, to reluctantly supporting Cuomo to enthusiastically supporting a Mamdani, a co-religionist, politics, with a few exceptions is an afterthought, a major question: what's your favorite chinese restaurant?

Great piece Michael! So thorough and well written. Maybe I can just share this instead of writing about the neighborhood myself! When I was at Marine Park last week I was amazed at all the Sliwa signs. Maybe he’s going to make more noise than the polls suggest?