The Making of The People’s Republic

A Decade in Astoria, Queens

In a corner of Queens County, bounded by the East River, straddling the Long Island Expressway, with views of the Manhattan skyline, lies the neighborhood of Astoria.

Renamed for John Jacob Astor, the wealthiest man in the United States, class politics have always shaped Astoria. Always a home to immigrants, Astoria was first settled by the Dutch, English, and Germans in the 18th century, followed by the Irish in the 19th century, and Italians and Jews in the early half of the 20th century. Astoria’s modern day culture and demographics, nonetheless, can be traced back to the 1960s, when a large wave of Greek immigrants settled in the neighborhood. The Greeks and Italians soon opened tavernas and trattorias, erected churches, and purchased single family homes, becoming Astoria’s dominant ethnic groups.

For the decades thereafter, the political character of Astoria mirrored that of other outer-borough, white ethnic neighborhoods: erstwhile supporting liberal icons (Jack Kennedy, John Lindsay) before swinging right towards reactionaries (Mario Procaccino) and conservatives (James Buckley). The Democrats who represented Astoria opposed forced busing and abortion, but supported the Vietnam War and the death penalty; all positions that matched their socially-conservative (and often deeply religious) constituents. Archie Bunker, the fictional (and bigoted) father from the 70s sitcom All In The Family, lived in Astoria. In the show, Bunker is an “early supporter of Ronald Reagan and correctly predicts his election in 1980,” all while railing against “commies, women’s libbers, and ‘unpatriotic’ peace protestors.” (Bunker’s prediction was correct, as Reagan won Astoria both times when he ran for President). In political commentary, the Archie Bunker vote became shorthand for the bloc of urban, white, working-class men; and for the latter half of the 20th Century, such shorthand was an apt description of Astoria’s political culture, as voters oscillated between moderate Democrats and right-wing Republicans. By the 2000s, the neighborhood had settled into a familiar pattern: reliably blue at the federal level, with a pinkish hue at the local level. Al Gore and John Kerry comfortably carried Astoria versus George W. Bush, but so did Republican Michael Bloomberg in three consecutive mayoral elections (although by less and less every time). Down the ballot, the neighborhood routinely elected conservative Democrats, often from the Vallone family, a multi-generational staple of the Greek community (Peter Vallone Sr. and Peter Vallone Jr. represented Astoria in the City Council continuously from 1974 to 2013).

In the 2008 Democratic Presidential Primary, an instructive tilt between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, the future president performed well in many of the neighborhoods that would soon become the face of the progressive left. Obama won Greenpoint, Carroll Gardens, Fort Greene, and Park Slope, home to the city’s emerging professional class. But in Astoria, Clinton won every block: Greek and Italian homeowners, Hispanic families in Section 8 housing, market rate renters, and public housing residents. Obama, who campaigned on ending the War in Iraq and inspired scores of young people to organize and engage in the political process, was shut out.

Indeed, Astoria would have seemed like an odd place to start a political revolution.

There were few signs (and even fewer elections) to the contrary until 2016, when Clinton returned to once again seek the Democratic nomination for President. Her opponent, Bernie Sanders, an unabashed democratic socialist and longstanding critic of capitalism, was making his metaphorical “last stand” in New York. However, while Sanders won 49 of New York’s 62 counties, Clinton crushed the Vermont Independent in the state’s urban centers, particularly with Black and Latino working-class voters and the affluent liberal intelligentsia of Manhattan. In defeat, Sanders nonetheless cultivated support from younger, college-educated voters in Brooklyn and Queens (in addition to his pronounced rural appeal). The 2016 Democratic presidential primary cohered the first iteration of the “Commie Corridor.”

Clinton, compared to her 2008 performance, regressed considerably in Astoria, more so than any other neighborhood in the five boroughs. After winning every precinct eight years prior, Clinton held onto only a handful: Astoria Houses, the public housing development on the Hallets Point peninsula; Marine Terrace, a longtime Section 8 housing development, where a plurality of residents are Hispanic; Queensview Apartments, a mix of limited equity and open market cooperatives home to older voters; and Astoria Heights, a triangled enclave of Italian and Greek homeowners in the neighborhood’s northeastern corner, a 25-minute walk from the subway. (For decades, Astoria Houses and Marine Terrace were Black and Latino islands of Democratic blue in a neighborhood awash with Republican red).

On blocks where renters were a majority of the electorate, Sanders crushed Clinton. However, few attributed Sanders’ overperformance in Western Queens to a class-based politics that appealed to renters. After all, the Brooklyn native had also outpaced Clinton with (increasingly disaffected) white ethnic Democrats across the city (Sanders won Bay Ridge, Maspeth, Marine Park, and Tottenville). Given Astoria’s historic political and demographic identity as a bastion of white ethnic voters, Sanders’ strong performance did not trigger alarms for longtime Democratic incumbents. Perhaps it should have.

Nonetheless, there were those who sensed opportunity. Millennials were raised in the wake of September 11th, watched in horror as the United States pursued a futile and destructive War in Iraq, and came of age during the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Those who believed in electoral politics were left disappointed by Barack Obama’s tenure, and embraced the decidedly left-leaning, class politics of Bernie Sanders. Throughout the 2010’s, many college-educated millennials, priced out of the urban core and confined to the renter class, found themselves in Astoria, a family-friendly neighborhood with a relatively short commute to Manhattan. They entered into a political vacuum, with few local institutions and an electorate amidst dramatic change. The older, more conservative Italian and Greek voters, which once reliably anchored Astoria’s electorate, were aging (and realigning) out of the Democratic base. But Rep. Joe Crowley failed to notice the shifting political tides.

A creature of machine politics, Crowley was hailed as the proverbial “King of Queens,” despite rarely competing in competitive elections (preferring to knock his opponents off the ballot through legal maneuvers). Nonetheless, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a 28-year-old waitress and native of the Parkchester section of the Bronx (who once described a run against Crowley as “literally political suicide”) was undeterred by the incumbent’s reputation. Outspent by a 10:1 margin, the Ocasio-Cortez campaign relentlessly pounded the pavement. Knocking doors, in a dense and residential neighborhood like Astoria, was straightforward, with walkup apartment houses and single-family homes easily accessible. In a single shift, a few dozen volunteers could cover thousands of doors (always leaving a palm card behind), having hundreds of conversations along the way. In a low-turnout Democratic primary, volunteer canvassing proved to be a tremendous competitive advantage. On June 26, 2018, such efforts paid off in the upset of the decade. In Astoria, Ocasio-Cortez, the democratic socialist who called for the abolition of ICE, crushed Crowley, who had endorsements from every local elected official. At the block-level, the carnage was even more pronounced, as Ocasio-Cortez won all but two blocks (Marine Terrace and a sliver of Astoria Heights). On most blocks, she earned more than 75% of the vote.

“We beat a machine with a movement,” she smiled.

If Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s victory was an earthquake, Astoria was the epicenter.

The following year, NYC-DSA, amidst an epic membership revival during the first Trump administration, audaciously endorsed public defender Tiffany Cabán, a de-carceral reformer in the mold of Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, for Queens District Attorney. In the wake of Crowley’s stunning defeat, the wounded “Queens Machine” rallied behind Melinda Katz, a former City Council member and sitting borough president. The race mirrored AOC vs. Crowley: an underfunded democratic socialist with robust grassroots support, facing a moderate liberal with near-uniform backing from the political establishment. But the narrative of the favored candidate being “asleep at the wheel” was gone. In a contest that spanned an entire borough, with existential implications for the Democratic machine, the Katz campaign strategically retreated to Southeast Queens, home to the city’s Black middle class, conceding Western Queens to Cabán, a clear indication of the left’s growing political power. Armed with “a large number of young people who, for the right candidate, would be willing to work very hard for free,” Cabán won more than 75% of the vote in Astoria, with the highest voter runout of any neighborhood in Queens County. NYC-DSA wasn’t just winning over new residents and bringing people into the political process, but growing their support among the neighborhood old guard: Cabán won the working-class renters of Marine Terrace and the homeowners of Astoria Heights. In the end, Cabán lost by just 60 votes, less than one-tenth of one percent.

Even in defeat, the People’s Republic of Astoria was born.

It’s one thing to win a campaign that spans a congressional district or borough, where your opponents may be focused elsewhere, but what about at the neighborhood level? This, in many respects, is the last level of building durable political power.

On a brisk morning in October, the three figures who helped usher in a new political era for Astoria — Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Tiffany Cabán — took the stage at Queensbridge Park. In the crowd was the fourth, Zohran Mamdani.

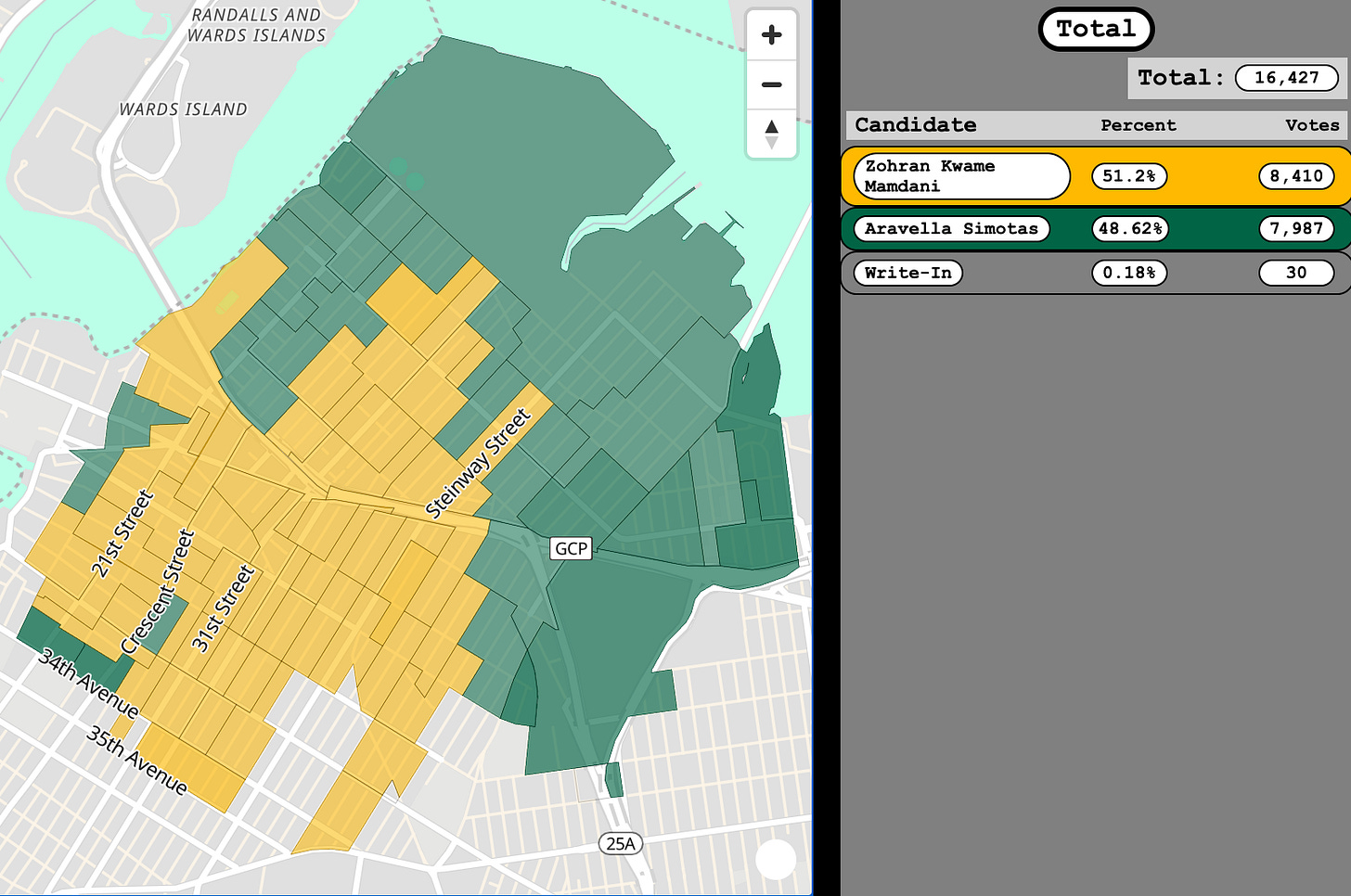

As Sanders implored the audience, in his trademark Brooklyn accent, to “fight for someone you don’t know,” Mamdani canvassed the crowd, urging the smallest of donations to his own campaign. “I’m running on Bernie’s platform in Astoria,” he said with a smile. Mamdani was running against the incumbent, Aravella Simotas, a lifelong resident of Astoria. Homegrown in the neighborhood’s Greek community and with ties to the Queens Democratic Party, Simotas had a plethora of connections that Mamdani, who moved to the neighborhood the year prior, did not. Establishing a clear contrast with Simotas, an inoffensive left-liberal who had been hailed for her work combating sexual harassment, proved to be a difficult endeavor for Mamdani; City & State even published an article, with the subtitle: “Aravella Simotas and DSA-backed Zohran Mamdani compete over the same platform in Astoria,” underscoring this dynamic. Further complicating life was the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced all campaigning inside. Mamdani’s greatest assets, volunteer door knocking and in-person interaction, were eliminated per public health guidance.

Simotas, given her ties to the community, was a far stronger opponent than Crowley or Katz. She would win Queensview Apartments by 46%, charming left-liberal cooperators who were apprehensive about a socialist incursion, and Marine Terrace by 30%, reminding working-class voters she was a known quantity (unlike her fresh-faced opponent). In Astoria Heights, Simotas crushed Mamdani, as the Greek community rallied to her defense. Blocks that had loudly voted for AOC and Cabán eschewed their comrade, Mamdani. Old Astoria would not go down without a fight.

But Zohran Mamdani was working to expand the electorate. His campaign knocked on the doors of Muslim independent voters in the dead of winter to re-register them as Democrats so they could vote in the primary. During Ramadan, at the height of the pandemic, the campaign distributed six hundred meals every day. “Bringing forth Bernie Sanders’ vision,” Mamdani said, “means not only fighting for a political revolution but transforming the electorate.” Since the 1970s, thousands of Arabs and Muslims had immigrated to Astoria, establishing a commercial corridor along Steinway Street, the same thoroughfare where the NYPD illegally surveilled Muslims on the basis of their faith after September 11th. And, amidst the narrative of a political tug-of-war between the millennial, college-educated renters and their baby boomer, home-owning counterparts, a crucial piece of Astoria’s fabric had been left out.

No longer. Mamdani’s best precinct, which delivered the Muslim socialist more than two-thirds of the vote, included the “Little Egypt” blocks of Steinway Street. When the votes were tallied at Queens Borough Hall, Mamdani prevailed by the slimmest of margins. “423 Astoria Patriots,” in the words of Mamdani’s photographer, Kara McCurdy, “changed the course of history.” The close result was cited as a reason for The Left to not become too bullish, but the opposite was true. Mamdani’s victory was the culmination of a sea change; a democratic socialist political movement had not only arrived, but was there to stay. They too, were now part of the community.

The “Mamdani Coalition” — young people, renters, Muslims, South Asians — that eventually propelled ZOHRAN to City Hall was first built in Astoria.

Five years later, Zohran Mamdani was once again on the ballot in Astoria — along with every other neighborhood in the five boroughs (by then, two more NYC-DSA candidates had won office in Astoria: Tiffany Cabán for City Council, and Kristen Gonzalez for State Senate). Running for mayor, Mamdani re-created his Astoria Coalition across New York City: running up the score with renters (both market rate and rent-stabilized) in places like Upper Manhattan; sweeping the Commie Corridor from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Bushwick; outpacing the competition among college-educated professionals in Fort Greene and Park Slope; while inspiring record turnout from Muslims in Jamaica Hills, South Asians in Kensington, and Arabs in Bay Ridge.

In Astoria, where it all began, the results were profound: 81% of the vote, the highest of any neighborhood in New York City (tied with Bushwick and Ridgewood). Mamdani had not only engaged an impressive number of newer voters (expanding the Astoria electorate by more than 50% compared to four years prior), but worked tirelessly (and successfully) to win over longstanding residents of the neighborhood. In the Primary, he swept the familiar faces of Astoria Heights, Marine Terrace, and Queensview Apartments, the first NYC-DSA candidate ever to do so. In the General, the lone blocks of the neighborhood captured by Andrew Cuomo months earlier — Astoria and Ravenswood Houses, public housing developments home to older, lower-income Black and Latino voters — swung to Mamdani. While still a neighborhood of contradictions and limitless nuance, Astoria was awash in blue.

In many respects, the demographic and cultural changes of Astoria, from a blue-collar community of white ethnic immigrants, to a polyglot of professionals, young families, Muslims, South Asians, and tenants, reflects that of New York City as a whole. The throughline, between the old and new Astoria, is a diverse and nuanced middle-class. Once a political afterthought, let alone an outer borough outlier, Astoria now shapes the whims of discourse and possibility far beyond the five boroughs.

This week, Diana Moreno, another democratic socialist, won the special election to succeed Mamdani in the Assembly. Moreno easily prevailed, netting 74% of the vote, winning every block of Astoria and Long Island City, the latest in a decade-long line of victories for The Left in Western Queens. In the telling of the Queens Eagle, “Moreno’s stiffest competition was herself. Carrying both the Democratic and Working Families ballot line, Moreno, the Democratic nominee, beat out Moreno, the Working Families nominee, by a mere 200 votes.” In 2018, Astoria led the charge against the infamous “Queens Machine,” dethroning their once-vaunted leader; now, the neighborhood is powerful enough that County Chair Greg Meeks (Joe Crowley’s successor) declined to even put up a fight, bending the metaphoric knee by giving Moreno the Democratic line. He knew a democratic socialist victory was inevitable.

Moreno, undoubtedly, has big shoes to fill as Mamdani’s successor; perhaps larger than any other first term legislator in New York history. On Monday, Jacobin published my profile of her, which I encourage all of you to read. I rarely publish magazine-length pieces on state legislature candidates, but I wanted to write something that people, even years from now, could reference to gain a better understanding of who she is. Moreno’s future, and the movement she represents, are undeniably bright.

Ten years ago, Astoria had no democratic socialist elected officials. Now, the People’s Republic is the only neighborhood in the United States with socialist representatives at the city, state, and federal levels of government.

Last June, scores of volunteers fanned out across Astoria, wearing summer shorts and carrying water bottles, braving triple-digit heat to welcome voters at polling sites, hand out literature to commuters, and chalk intersections and street corners. In November, hundreds more reconvened to repeat the routine, armed with jackets and jeans, navigating less daylight and twice the number of voters. This February, as piles of frozen snow lined the sidewalks, and the temperature “peaked” at 30 degrees, many of the same volunteers (new and old) eagerly greeted parents at school dismissal, this time wearing hats and gloves. Such was the case no matter the season nor the campaign. To these committed locals, such acts have become a part of life, at a time when everyday people are drifting further and further apart. They come early and stay late for the beloved face on the palm card, sure, but they return, over and over again, because of one another. Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name. In the words of Astoria’s newest Assemblywoman, Diana Moreno, “my comrades come from different backgrounds, faiths, and ethnicities, but we find such a healing point of connection in our belief and vision for a world where people have their basic needs met. When you play a role in the movement, you feel alive.”

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Would add just a few things about how we pivoted when Zohran’s Assembly race was disrupted by Covid and we couldn’t knock doors. We’d already knocked hundreds of doors by March 2020 and had made inroads. Mutual aid became important, as you note. Relational organizing became huge, as we leaned on already established networks. We hand wrote thousands of postcards which was a wonderful personal touch. And we chalked all over Astoria. People were confronted by colorful displays of Zohran’s key issues everywhere they went, and in the Spring, and right up until the primary, people were out in numbers and everyone noted the chalkings.

DSA not DNC