New York City's Rainbow Coalition - Part I: John Lindsay's Forgotten Urban Crusade

The first installment of an original series on the history of progressive, multiracial coalitions in New York City.

“Our flag is red, white and blue, but our nation is a rainbow — red, yellow, brown, black and white — and we’re all precious in God’s sight. America is not like a blanket — one piece of unbroken cloth, the same color, the same texture, the same size. America is more like a quilt: many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread. The white, the Hispanic, the black, the Arab, the Jew, the woman, the native American, the small farmer, the businessperson, the environmentalist, the peace activist, the young, the old, the lesbian, the gay, and the disabled make up the American quilt.”

These words, delivered by the Reverend Jesse Jackson during his keynote address at the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco, embodied a generation of progressive political advancement in the United States.

While Jackson was not the first to champion the concept of a “Rainbow Coalition” - the idea was first coined by Fred Hampton of the Black Panthers (in conjunction with organizations like the Young Lords, Students for a Democratic Society, and the socialist Lincoln Park Poor People’s Campaign) to define their multicultural direct action-based movement rooted in racial and class solidarity - he nationalized the use of the term in political contexts.

Amidst an era defined by Reaganomics and the increasingly neoliberal orientation of the Democrat Party, Jackson’s unabashedly progressive Presidential campaign - which included calls to reverse Republican tax cuts to finance social welfare programs, cut the Department of Defense budget, create a single-payer healthcare system, provide free community college, and resurrect the Works Progress Administration to rebuild infrastructure and create jobs - supported by a left-coalition which transcended race and class, remained a clear outlier in National politics.

However, in municipal politics, left-leaning and reform-oriented coalitions - which united anti-machine liberals with working-class Blacks and Latinos - had emerged throughout the 1970’s, winning competitive Mayoral races in Los Angeles, Detroit, and Philadelphia - culminating in Harold Washington’s seminal 1983 triumph, coincidentally in Jackson’s de-facto political home of Chicago, where the South Side Congressman upset both the incumbent-Mayor and the Windy City’s infamous political machine.

Yet, even amidst this period of urban reform and multiracial coalitions, New York City thrice elected Ed Koch, a conservative, business-friendly Democrat, who assembled a citywide coalition of liberal Manhattanites and outer borough working-middle class whites, leaving his political opposition frustrated and increasingly divided. Despite failing to attain the Democratic Nomination, Jesse Jackson’s Presidential campaigns and “Rainbow Coalition” was instrumental in shifting the trajectory of progressive politics in New York City - creating the blueprint for ousting Koch, and elevating David Dinkins, the city’s first Black Mayor, into City Hall.

But, what if I told you that New York City had already elected a reformer backed by a multiracial coalition - long before Koch, Jackson and Dinkins remade the city’s political landscape? Surely, you would want to know what happened, and why his progressive coalition (ahead of its time in many ways) fell apart under the stressors of governing and the fault lines of New York City’s ethnic politics? Here, I sought to retrace the history of citywide “Rainbow Coalitions” throughout the five boroughs - which I have loosely defined as liberals, Blacks, Latinos, and the youth electorally uniting behind progressive politics to defeat conservative opposition.

My hope is that this piece, largely focused on the polarized politics of the late 1960’s, still resonates today, given that the dynamics of race, ethnicity, class, and ideology continue to shape both the outcomes (and narratives) of municipal elections throughout the United States. Today, the left must continually contend with the difficult realities of assembling multi-faceted political and governmental coalitions - so that power cannot only be achieved, but retained.

Let’s look back at John Lindsay’s New York City - from the tensions of community control in Ocean Hill-Brownsville to building low-income housing in Forest Hills, in a city which fully embodied the trials and tribulations of the late 1960’s.

“Historically, New York is a pattern setter. If it should prove ungovernable or explode in bitterness, no other city could feel secure in a time of increasing racial and ethnic polarization.” (TIME)

It is difficult to understate just how much New York City has changed since 1965 - the year idealistic reformer John Lindsay captured City Hall.

New York City was coming down from its post-war high. Millions of Blacks and Puerto Ricans had arrived in the preceding decades seeking economic opportunity - only to be geographically isolated by urban renewal, condemned to redlined neighborhoods, segregated schools, and blighted housing. Manufacturing jobs, once the lifeblood of working class immigrants and a ticket to upward mobility, had traded New York’s waterfront for suburbia. At the behest of Robert Moses and the automobile, arterial highways carved through Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx - displacing thousands of residents - all while public transit continued to be neglected. These traceable conditions and economic despair fueled New York’s rising crime, as murders more than doubled between 1955 and 1965. As conditions throughout the city worsened, middle-class whites in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx fled en masse - exceeding over one million departures, hallowing out the city’s tax base, and in turn diminishing many of the social services desperately needed by Gotham’s low-income newcomers. Was New York City… ungovernable?

Politically, New York orbited the “three I’s” - Italy, Ireland, and Israel - with ethnicity and religion shaping the city’s elections, to the point where “balancing” tickets for Mayor, Comptroller, and City Council President (i.e. choosing one Jews, Italian, and Irishman) became commonplace for much of the 20th century. Nonetheless, Tammany Hall, the notoriously corrupt Irish political machine, remained a shell of its former self, as movements to “reform” the local Democratic Party - led by Eleanor Roosevelt and former Governor/Senator Herbert Lehman - weakened the influence of political bosses in the late 1950’s.

Clashes between liberal Jews, the heartbeat of the reform movement (and routinely the crucial swing voters in citywide elections), and working-class Catholics, the electoral foundation of outer borough Democratic machines - straddled along ideological and religious lines.

Vincent Cannato, the preeminent John Lindsay biographer, described the gulf between “regular” and “reform” Democrats as “wide as the distance separating the worlds of the white, working-class, home-owner in Queens and the Ivy League reform lawyer living in Greenwich Village or the Upper West Side. Though vastly outnumbered, reformers were better educated and more articulate than their parochial counterparts and, more importantly, had the media behind them.”

While liberal reformers dominated the majority of Manhattan, the citywide electorate - even amidst the early stages of white flight - remained anchored by Irish Catholics, Italians, and middle-class Jews throughout the outer boroughs. Yet, both Blacks (Beford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, Springfield Gardens - in addition to Harlem) and Puerto Ricans (East Harlem & the South Bronx) now comprised a larger share of the vote than ever before.

For over sixty years - between the Civil War and Herbert Hoover’s 1928 defeat on the heels of the Great Depression - Black voters across the northeast voted en masse for the party of Abraham Lincoln and Reconstruction. However, upon the implementation of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, which strengthened the social safety net and provided thousands of public works jobs throughout urban America, New York City’s Black voters swiftly migrated to the Democratic Party - ultimately peaking in the 1964 Presidential Election, with the reactionary Goldwater winning less than 10% of the Black vote. Since the New Deal, the FDR-adjacent Mayor, Fiorello Laguardia, was the only Republican who managed to retain support among Black voters.

“White Southerners supported the Democratic Party as the party opposing Lincoln, the Union and Reconstruction. The white urban working class backed the Democratic Party as the defender of unions and workingmen. The Republican Party became defined by its defense of the Union, its support for business, and its opposition to urban machines. By the end of the 1960’s, the reform attacks on urban machines destroyed inherited party allegiance in the urban North, while the civil rights movement destroyed it in the urban south.”

(Vincent Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

New York City, and John Vliet Lindsay, sat on the vanguard of a significant political realignment.

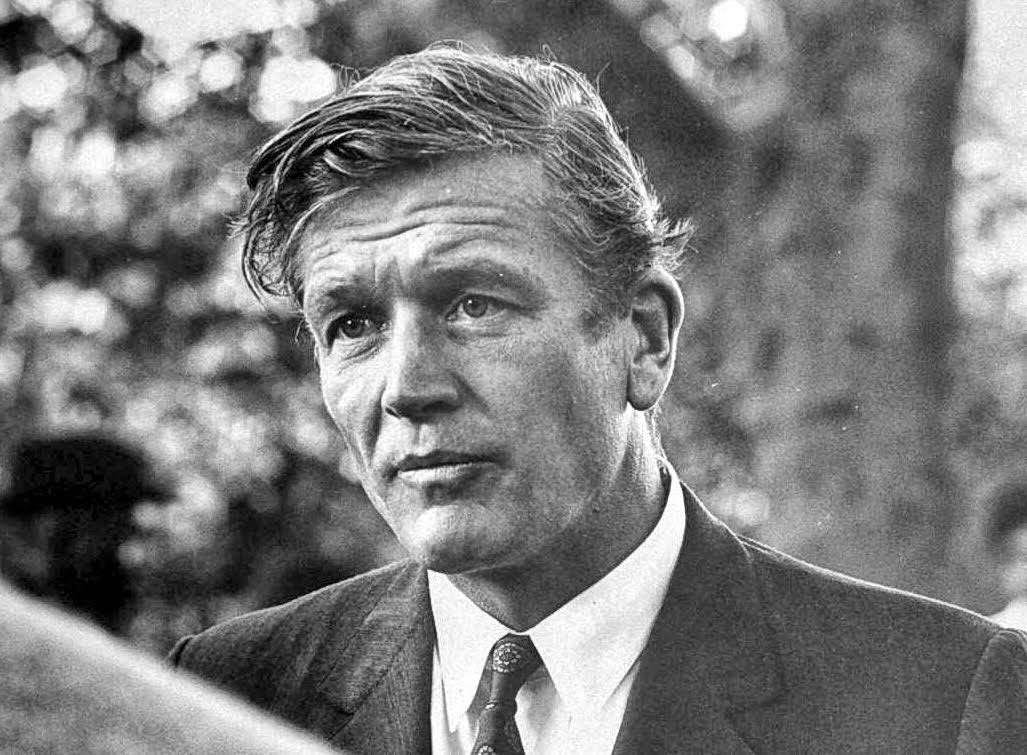

A liberal Republican - back when such possibilities existed - Lindsay was cut from a political cloth similar to many New York titans of his era, like Senator Jacob Javits and Governor Nelson Rockefeller. A native of West End Avenue who traversed many of the northeast’s premier private institutions - from Buckley to St. Paul’s to Yale University - Lindsay eschewed a promising law career in favor of politics, intent on advancing the plight of urban cities and racial minorities.

Lindsay found a comfortable home within the confines of New York’s 17th Congressional District, colloquially referred to as the “Silk Stocking” district, which encompassed many of the City’s exclusive enclaves and influential institutions - stretching from the Upper East Side to Greenwich Village. A reliable spokesperson for liberal causes at home and abroad - the tall and handsome Congressman enjoyed considerable popularity amongst his constituents.

Amassing a reputation for his political independence - famously declining to endorse fellow-Republican Barry Goldwater in the 1964 Presidential election - Lindsay’s ties to the GOP stemmed from an inherent opposition to Democrat clubhouse politics, or “bossism”, in the mold of beloved former Mayor (and fellow Republican) Fiorello Laguardia.

The aforementioned Laguardia, outnumbered by Democrats three-to-one amidst the New Deal Era, led a fusion coalition composed of his ethnic brethren(the Italians), and liberal Jews - the most ideological voting bloc at the time - coupled with the relatively small Black population, to three consecutive terms while earning an eternal place in New York City lore as Gotham’s greatest Mayor. However, Lindsay, a protestant of English and Dutch descent, lacked the same ethnic foothold that proved instrumental in Laguardia’s triumph - a crucial ingredient to mounting an upset campaign thirty years later.

Despite his Republican affiliation, Lindsay’s distance from the Democratic clubhouse and staunch liberal bona fides - particularly with respect to Civil Rights - made him an attractive Mayoral aspirant to these reform-minded voters in 1965. While the Democratic machine was not scandal-scarred - as was the case in past reformer upset victories - a sweeping sentiment emerged that New York City was headed in the wrong direction, evidenced by the beginnings of a middle-class exodus. Such prevailing anxiety opened the door for an anti-establishment candidate, with Lindsay eager to attribute the “urban crisis” of the white middle-class and low-income racial minorities to failing schools, inadequate housing, and a lack of public safety.

Like Laguardia, who ran on the American Labor Party ballot line, Lindsey entered the Mayoral race as a “fusion” candidate also backed by the Liberal Party. Guided by the influential hand of power broker Alex Rose, the Liberal Party “bestowed the imprimatur of liberalism and good government, which was worth more than the two hundred thousand votes it controlled.” Presiding over a crucial swing electorate, Rose fancied Lindsey as an ambitious reformer who was sensitive to racial issues and politically independent - particularly when compared to his two opponents - Democrat Abe Beame, a favorite of the infamous Brooklyn Boss, Meade Esposito, and William F. Buckley Jr., a controversial writer and political commentator running on the Conservative Party ballot line.

Beame’s ties to Esposito and the Brooklyn clubhouse coupled with a less-than-inspiring stage presence, was an ideal contrast for Lindsay, who impressing spectators in debates, amassed over twenty thousand volunteers, and opened hundreds of campaign storefronts throughout the five boroughs, while routinely engaging in long walks through Black, Puerto Rican, and white ethnic neighborhoods. “He is fresh and everyone else is tired” became the unofficial motto of the campaign.

While Lindsay’s youthful energy and good looks frequently elicited comparisons to John F. Kennedy, Beame sat on the opposite end of the spectrum - routinely overshadowed by New York’s junior Democratic Senator, former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, whose charisma on the campaign trail made the pride of City College’s accounting department look dull.

Nonetheless, Lindsay frequently encountered resistance with white ethnics in the outer boroughs, many of whom supported Buckley and relished the opportunity to relentlessly heckle the WASP from the Upper East Side, whose campaign storefronts were frequently picketed amidst chants of “Lindsay loves communists”. Appealing for a Civilian Complaint Review Board at Richmond Hill High School, Lindsay was drowned out by chants of “Judas” - in reference to Lindsay’s refusal to endorse Barry Goldwater one year prior.

Yet, despite his distance from the Republican Party, and his collective embrace of the “Fusion” label, Lindsay’s coalition - “young professionals eager to displace machine loyalists from municipal government, business interests opposed to traditional Democratic fiscal policies, and those concerned with the social welfare of the City’s low-income residents” - was rife with inherent ideological conflicts, namely between “those favoring traditional fiscal conservatism and those favoring greater government spending to reduce inequality, improve city services, and ameliorate the situation of Black and Puerto Rican newcomers.” This tension defined much of Lindsay’s administration, illustrating the precarious nature of maintaining his multiracial electoral coalition.

After trailing in every Herald Tribune poll for the duration of the campaign, Lindsay found his stride over the final month, sharpening his attacks on the conservative Buckley by linking him to fascism and reaction, which energized his liberal base and played to “the historic fears of Jewish and Black New Yorkers”. In doing so, Lindsay risked conceding the white ethnic vote - particularly amongst Irish Catholics, a majority of the police department - betting that his Republican status would keep just enough Irish and Italians in his column and that Conservative Democrats would break for Buckley over Beame.

Crucially, Lindsay tactfully navigated the politics of rising crime throughout the city - the most pressing issue for white voters regardless of ethnicity or class. One week before election day, the Herald Tribune ran a front-page series titled “The Lonely Crimes” emphasizing this prevailing fear, which amounted to a “muted portrayal of young Blacks and Puerto Ricans preying on elderly whites in transitional neighborhoods.” In what was increasingly seen as a racialized issue, Lindsay did not abandon his liberal principles, telling voters “crime is committed by every race and group and is not limited to any one,” pledging to add another 2,500 officers to the police force.

While Lindsay prioritized reaching out to Black and Latino voters over the final weeks, his support with Manhattan’s liberal electorate was cemented following the surprise endorsement of Democrat Ed Koch. Before adopting a more conservative orientation during the 1970’s, Koch, a Greenwich Village District Leader who had twice defeated then-Tammany Hall Boss Carmine DeSapio, hailed from the highly-influential Village Independent Democratic Club, and was regaled as a political icon amongst reformers. To many of Lindsay's closest confidantes, Koch’s eleventh hour decision to back the liberal Republican swung the outcome of the race.

On the eve of the election, the urban crusader eschewed rallying his liberal, upper-class base in favor of spending fourteen hours in Harlem and the South Bronx. Pledging to add non-police members to the Civilian Complaint Review Board and integrate the City’s public schools, Lindsay sensed soft support for Beame amongst working class minorities throughout the City’s low-income neighborhoods.

While Lindsay’s triumph by four percentage points - in one of the highest turnout elections in New York City history - is primarily attributed to his dominant performance amongst Manhattan liberals, traditional Republican strongholds in Queens and Staten Island, and significant inroads with middle-class Jews in neighborhoods like Riverdale, Flatbush and Forest Hills - a closer examination shows that the Upper East Side Congressman performed better with Blacks (40%) and Puerto Ricans (25%) than any Republican since Laguardia - the importance of the latter evidenced by the neighborhoods Lindsay visited in the wake of his victory.

“Ignoring his Manhattan district and white Catholic areas in the outer boroughs, Lindsay traveled to Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, and the middle-class Jewish Rego Park neighborhood in Queens to celebrate the victory of the first Republican Mayor in twenty years” (Vincent Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

Alex Rose helped deliver almost three hundred thousand votes to Lindsay - over one fourth of his total and twice his margin of victory - which crucially cut into Beame’s base of working-class Jews, particularly in neighborhoods like the Upper West Side, Flushing, Midwood and Coney Island. While support for Lindsay amongst white ethnics - Italians, Irish, and Germans - held relatively firm, Buckley’s strong showing in Republican-aligned Assembly Districts in the outer boroughs - like Bensonhurst, Maspeth, Douglaston, and Throgs Neck - foreshadowed the headwinds Lindsay would face later in his quest for a second term.

Many of the middle-class voters in the outer boroughs who had split between Beame, Buckley and Lindsay quickly soured on the new Mayor, forcing Lindsay, who became increasingly estranged from his political home, to build a new governing and electoral coalition midway through his first term.

As the exaltant Lindsay graced the front covers of Time and Newsweek, many pundits declared that the future of GOP politics belonged to the Urban Crusader, championing a new progressive Republicanism.

“For a moment on the night of November 2nd, 1965, a man could believe that the mayoralty of New York City might lead to the White House, a city could believe that a handsome mayor’s righteous moralism would revive the spirit of Camelot and raise the fortunes of a city in decline, and a nation could still put its faith in liberalism to maintain its values, affluence, national security, and civil order. Within four years, all of those beliefs would become untenable.”

(Vincent Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

“Such a diverse coalition - Silk Stocking Manhattan Republicans, the city’s business elite, middle- and lower-middle-class white Catholic homeowners in the outer boroughs, liberal Manhattan reformers, middle-class Jews in the outer boroughs, and a small but significant number of Blacks and Puerto Ricans - was bound to fracture under the pressures of governing, as had all previous reform coalitions - but none had done so as dramatically or as furiously as would Lindsay’s.” (Vincent Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

Upon taking office in January 1966, many would have assumed that John Lindsay's carefully constructed coalition would not be tested at the ballot box until his re-election campaign three and a half years later. However, the newly minted Mayor would not be so lucky - as a referendum on Lindsay’s decision to reform the Civilian Complaint Review Board put the liberal reformer’s tentative coalition on the line, much less during the first year of his administration. Staring down the white ethnic working and middle-class rank and file of the NYPD, in addition to the uniformly Irish Catholic top brass, Lindsay bore witness to an electoral current that would dismantle his fusion coalition of one year prior - forcing the Mayor to readjust his electoral strategy.

Unlike today, where the NYPD is majority-minority - the Police Department of the Lindsay years was largely filled with lower-middle-class Catholics, who enjoyed the security of a civil service career that promised a degree of upward mobility. Before decamping for Nassau County and Staten Island post-white flight, much of the Police Department hailed from white ethnic working class neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens, a “world away from high-toned Manhattan or the slums of Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and the South Bronx.”

A Civilian Complaint Review Board designed to monitor police behavior, specifically their treatment of low-income Blacks and Puerto Ricans, had been a liberal cause for over fifteen years prior to the Lindsay administration. Despite its title, the “first” Civilian Complaint Review Board was staffed without any civilian members, only police representatives - but avoided scrutiny for over a decade after Robert Wagner reorganized the board to be more receptive to community concerns and civil liberties.

Yet, at the crux of the American Civil Rights movement amidst the fall of the Jim Crow South, Northern liberals began examining how open-housing laws, busing of schoolchildren, and police treatment of racial minorities perpetuated inequality within their own cities. Ted Weiss, a liberal reform-minded council member from the West Side of Manhattan (who later served in Congress), introduced a bill to the City Council for a Civilian Complaint Review Board consisting of nine civilians appointed by the Mayor. Despite renewed calls for reforming the department in response to the killing of a young Black man by an off-duty white police officer in Harlem, the Council and Mayor Wagner were content to let the Weiss bill die, hoping to wait out this political opposition. John Lindsay, at the time a candidate for Mayor, promised a “mixed” Review Board staffed with both police officers and civilian members.

Upon taking office, Lindsay quickly replaced police commissioner Vincent Broderick - a lukewarm supporter of a mixed CCRB who frequently feuded with the Mayor’s ambitious aides - with Howard Leary, the former Police commissioner of Philadelphia, whose handling of the 1964 riots won him praise from the NAACP. An Irish Catholic, Leary had experience working with an independent review board in Philadelphia, the deciding factor in Lindsay’s decision.

This marked a rather significant shift in municipal politics, as policing the city was becoming increasingly politicized, for better or worse, leading Leary’s appointments for Chief Inspector (the department’s highest ranking uniformed officer), Sanford Gaelik (a close friend of Liberal Party stalwart Alex Rose), and Deputy Chief Inspector, Lloyd Sealy, to face heightened scrutiny by the rank-and-file.

Within a fraternal department - Leary (from Philadelphia), Garelik (Jewish), and Sealy (Black) - were all viewed as outsiders. Nonetheless, Lindsay’s brash aides took great pleasure in breaking up the department’s “Irish Mafia,” noting that their efforts would bolster their standing amongst Blacks and Puerto Ricans. The Lindsay administration either overlooked, or entirely disregarded, the cultural significance and history of the NYPD within Irish communities throughout the City - with the Mayor’s calls to “humanize” the department implicitly seen as coded to make the police force less Irish.

On May 17th, 1966 - Lindsay made his move, issuing General Order No. 14, replacing the eleven year old board that had been staffed exclusively by police personnel with a new seven-person Civilian Complaint Review Board featuring four civilians and three policemen.

John Cassesse, the president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA), vowed to fight Lindsay’s CCRB tooth-and-nail, stating “I’m sick of giving in to minority groups with their whims and their gripes and their shouting.” A former beat cop from the Polish neighborhood of Greenpoint in North Brooklyn, Cassesse was eventually relieved as chief anti-CCRB spokesperson duties due to his ugly rhetoric, but not before invoking a Red Scare: “Communism and Communists are somewhere mixed up in this fight. If we wind up with a review board, we’ll have done Russia a great service.”

With 20,000 members, the PBA was one of the strongest interest groups throughout the five boroughs, and, upon being rebuffed by the courts, the City Council, and Albany, they began circulating petitions for a referendum to repeal the new board that would appear on the November ballot (YES = repeal the board, NO = keep the board). In one month, PBA volunteers garnered 51,852 signatures - well above the required 30,000 needed for a citywide referendum.

The moderate and conservative electoral forces - split between Beame, Buckley, and Lindsay one year prior - were now uniformly lined up against the new Civilian Complaint Review Board.

Editor’s Note: The Conservative Party submitted their own anti-review board referendum - netting 40,383 signatures - before later consolidating behind the PBA referendum.

With the battle brewing over the independent Review Board, news outlets began running stories where officers quoted reducing their activity for fear of being charged with police brutality, anecdotes that only emboldened CCRB opponents. Whatever semblance of a healthy relationship the Lindsay administration hoped to maintain with the City’s Police Department eroded almost instantaneously. While intra-NYPD opinion was heavily skewed against the review board, “the Guardians, a fraternal order representing 1,300 of the City’s Black policemen, called the board ‘the most important step toward wiping out fears and the unequal treatment suffered by members of our minority group’.”

Upper-middle class Manhattanites, mostly Protestants and Jews, were the review board’s biggest proponents, with their collective attitudes straddling between (1) the will to uniformly curb police brutality, foster a more holistic view of criminals, promote rehabilitation instead of repressive and (2) collective disdain and condescension towards white, working-class policeman whose lived experiences - both socially and professionally - were foreign to the more sheltered liberal reformers.

As the referendum gained steam, a group led by Bronx Borough President Herman Badillo (the first Latino to be elected to boroughwide office) and Black labor leader A. Philip Randolph, called the Federal Associations for Impartial Review (FAIR), was formed to streamline anti-referendum, pro-CCRB efforts - with a number of Lindsay campaign alumni heading the effort. Both of New York’s Senators, Jacob Javits and Robert F. Kennedy, backed the board - in addition to the City’s preeminent liberal institutions, like The New York Times Editorial Board. To the reformers, Civil Rights was the seminal issue of the review board, and fear of crime was not a substitute for bigotry.

Predictably, the campaign turned ugly, with anti-review board forces disseminating racially-coded advertisements on television, newspapers, and billboards: ”The addict, the criminal, the hoodlum - only the policeman stands between you and him.” The most infamous of which featured an image of a “young white woman in a raincoat standing alone in the dark outside a subway station” captioned with the ominous warning: “The Civilian Complaint Review Board must be stopped. Her life… your life… may depend on it.”

Given the saliency of crime, and its importance of electoral politics - pro-review board forces found themselves on the defensive, forced to assure voters, many of whom were fearful that the CCRB would tie the hands of the police, that the board would actually not be all that powerful - conceding “vote for the review board, it’s ineffective.” After consistently mentioning the rise of crime throughout his run for Mayor one year prior, Lindsay was noticeably silent on the issue upon taking office. Despite being in office for less than a year, the Mayor had already polarized segments of the electorate - particularly the middle-class by hiking taxes and the transit fare - with his lagging popularity hurting the pro-review board efforts.

The mastermind behind Lindsay’s ‘65 campaign, Deputy Mayor Bob Price, refused to help the pro-review board effort, condemning the matter as a losing issue. After running a grueling insurgency less than twelve months prior, much of the Lindsay apparatus was burnt out from campaigning and submitted a halfhearted effort the following year. Struggling to raise money and reluctant to run advertisements during the summer months - for fear of inciting a race riot - last-minute attempts to link the anti-CCRB efforts to far-right paramilitary organizations, like the John Birch Society, ultimately fell flat.

Even Lindsay’s hand-picked commissioner, Leary, who was chosen exclusively because of his experience working with an independent review board in Philadelphia, lent little support to the pro-CCRB efforts, afraid of upsetting the rank-and-file, a move that bitterly disappointed the Mayor.

While John Lindsay’s name was not on the ballot, his leading idea was.

In the end, the referendum to overturn the Civilian Complaint Review Board won 63% to 37% - with only twenty-one of City’s sixty-eight Assembly Districts voting “no” on the question. Lindsay’s winning coalition of ‘65 contracted. Notably, middle-class Jews and working-class Catholics in the outer boroughs coalesced to defeat the Mayor’s signature policy, the first instance in decades in which the two ethnic groups had civically-aligned on a major issue.

What was left was Lindsay’s base of Silk Stocking Manhattanites and Liberal reformers, where the “no” votes (pro-CCRB) were a majority, yet were nonetheless diluted compared to Lindsay’s vote share one year prior. However, Blacks and Puerto Ricans, predominantly low-income and segregated into neighborhoods like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Ocean Hill-Brownsville, and the South Bronx, forcefully voted against the referendum at a rate that, in many Assembly Districts, exceeded their high-income liberal counterparts.

Thus, even amidst a significant defeat, John Lindsay’s Civilian Complaint Review Board charted the course for a new electoral coalition anchored by progressivism and civil rights - capable of uniting white liberals, Blacks, and Latinos. However, on the other side of the coin, the CCRB referendum marked an inflection point for middle-class Jews in the outer boroughs, who, amidst a (racially) polarized electoral environment gripped by “law and order” rhetoric, voted in line with their Catholic neighbors.

Hence, the question became: would this aforementioned political current imperil John Lindsay’s re-election prospects? Or, could the incumbent Mayor build the Pro-CCRB effort, a losing plurality in 1966, into a winning Rainbow coalition in 1969?

As the social fabric of the United States frayed under the escalating and increasingly unpopular war in Vietnam, coupled with the tragic assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Senator Bobby Kennedy - New York City, and urban America writ large - was caught in the crossfire of white flight, economic contraction, rising crime, school integration and busing, the zenith of student protest politics, and a divided Civil Rights movement grappling with a leadership vacuum. Lindsay’s ‘65 electoral coalition - a precarious amalgamation of competing racial, ethnic and class interests - was a near-impossible governing coalition, and inevitably fractured.

Lindsay’s first-term earned him mixed reviews, putting him in a tenuous position heading into his 1969 re-election campaign. The failure of his Civilian Complaint Review Board proved to be a bitter disappointment, but Lindsay’s liberal bona fides were strengthened following his efforts to quell civil unrest following the assassination of Dr. King, famously walking the streets of Harlem that tumultuous night of April 4th. In contrast to Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, who ordered police to shoot-to-kill rioters and shoot-to-maim looters in the wake of King’s death, Lindsay proclaimed, “We happen to think that protection of life, particularly innocent life, is more important than protecting property or anything else… We are not going to turn disorder into chaos through the unprincipled use of armed force. In short, we are not going to shoot children in New York City.” Later in the year, picketing City Hall to demand a new union contract, many police officers brandished “We Want Daley” signs.

Labor woes were not solely confined to the police (or firefighters) - as, in a sign of things to come, the Irish-dominated transit workers went on strike during his first day in office: “Lindsay gives the impression of looking upon organized labor as a Democratic anachronism, arteriosclerotic in an era of social change, anti-integrationist in a city with a large nonwhite minority, complacent and irresponsible. That he is often right makes little difference to union leaders.” Divisive strikes, often centered around racial and ethnic lines, became commonplace throughout his first term. including amongst the majority-Italian sanitation union and the predominantly-Jewish United Federation of Teachers.

The latter, centered around community control of public schools in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, saw “strikes pit not only union against employer—the city—but, worse, black against white, Jew against Gentile, middle class against poor” - perfectly encapsulated the delicate nature of the Lindsay coalition.

With efforts to properly integrate New York City’s public schools failing, Black and Puerto Rican parents, dissatisfied with the inferior quality of their children’s education, began lobbying City Hall for community-controlled schools - outlined as “a sensible scheme to bring government to the people, particularly those who felt victimized by an impacted, intransigent white bureaucracy.” Here, these parents found a quasi-ally in John Lindsay, who favored the watered-down, more administratively-focused “decentralization.” As a result, the Board of Education created three “experimental” school districts in East Harlem, Two Bridges, and Ocean Hill-Brownsville, each led by a local elected-governing board armed with the power to set curriculum, determine school policy, and hire administrators.

A pro-decentralization consensus flourished among the city’s elites - from the Ford Foundation to The New York Times - as the former, headed by McGeorge Bundy, spent over $900,000 to fund community control experiments. Elite opinion, of which the patriarchal Mayor was associated, further fueled the animosity of the white middle-class - who condemned the moralizing of those privy to private schools: “Bundy and Lindsay were trying to reduce the power of others - teachers, educational bureaucracy, unions - to buy peace for themselves.”

If the experimental districts were deemed a success, Lindsay planned to decentralize all New York City public schools. However, the United Federation of Teachers, the nation’s largest local union at the time, viewed school decentralization as an existential threat to their existence. If citywide decentralization was approved, the UFT would be forced to negotiate with thirty-three separate school boards: “To many teachers and indeed to many members of other unions, the demand for community control—and the city's limited compliance—was nothing less than union busting.”

Union teachers, over two-thirds Jewish, feared being displaced from schools in Black and Puerto Rican communities. For context, despite constituting over half of the student population, Blacks and Puerto Ricans made up only 10% of teachers. Further muddying the waters, the Central Board of Education had been (incredibly) vague when outlining the “powers” of the respective local governing boards. On May 9th, 1968, this contention was immediately tested, as the Ocean Hill-Brownsville governing board dismissed nineteen educational personnel (13 teachers, 6 administrators), all of whom were Jewish, from J.H.S 271. The move drew a swift rebuke from UFT President Albert Shanker, who asserted that both the educators’ rights to due process and the union’s contract had been violated. Shanker ordered the UFT teachers back to school, where they proceeded to face a bevy of community opposition, requiring a police escort to even enter the building. In less than two weeks, an additional 350 UFT teachers would walk out of public schools in Ocean Hill-Brownsville in support of their colleagues - only to themselves be dismissed by the governing board one month later. Many of the replacement teachers, tasked with keeping the school staffed through the end of the year were “young, white members of the ‘New Left’ [who] nearly all supported community control.”

A socialist in his youth, Shanker developed into a rabid anti-Communist as an adult, helping to wrestle power away from the left-aligned Teacher’s Union (not to be confused with the UFT) in the late 50’s. Despite marching for civil rights in Selma, Alabama, liberal journalists came to revile Shanker for his role brokering the strikes at Ocean Hill-Brownsville, blaming him for deteriorating race relations. Jimmy Breslin once said that Shanker was “an accent away from George Wallace.”

On the eve of the first day of school in the Fall of 1968, the governing board - despite local court rulings in favor of reinstating the dismissed teachers - refused to back down, telling Lindsay, “We will no longer act as a buffer between this community and the establishment …. This community will control its schools and who teaches in them. We do not want the teachers to return to this district.” The following day, fifty-four thousand of the fifty-seven thousand public school teachers (93%) went on strike.

This continued - on and off - for two months, with the UFT reaching a series of agreements with the Board of Education that hinged on the reinstatement of dismissed teachers to the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district. The local governing board, which was entirely left out of negotiations with the UFT and never consented to the reinstatement plan, predictably did not comply - culminating in a devastating series of strikes.

For thirty-six days in the Fall of 1968, over one million public school students could not attend class because of the strike.

“Ironically, the area least affected by the strike [was] Rhody McCoy's eight-school Ocean Hill-Brownsville district. Recruited during the summer from all parts of the country, McCoy's temporary teachers form one of the brainiest public school staffs in the country. Eager, dedicated and inventive, with a heavy emphasis on the Ivy League—’I'm a bum,’ quips one principal, ‘but all my teachers wear Brooks Brothers suits'’—they come early and stay late, refusing to bow to the stale pedagogic commands that emanate from 110 Livingston Street, the Board of Education's central office in Brooklyn. Many have attended law school, and regular teachers complain bitterly that they are in Ocean Hill only to escape the draft.” (TIME)

Less than one generation removed from the Holocaust, many Jews were keenly sensitive to charges that the majority-Black governing board was antisemitic - despite nearly half of the district’s new hires being Jewish. Shanker steered the narrative away from community control to focus on issues of “Black antisemitism,” inflaming the fears of the white middle-class: "Every day this strike goes on, things are getting worse. You can sense there is much more anti white feeling among blacks and much more anti-black feeling among whites."

Armed with leverage, New York State acquiesced to the UFT’s demands. Asserting state control over the school district - the dismissed teachers were reinstated, the principals appointed by the now-defunct governing board were reassigned, and a trusteeship was established to run the district until the end of the school year. Soon after, many holdovers who remained sympathetic to the community control model were “purged.”

UFT Teachers returned to work, and the experiment at Ocean Hill-Brownsville faded from public consciousness. While New York state passed a new “decentralization” bill that gave the city thirty elected school boards, the boards held little power or influence - a far cry from Lindsay’s original plan to decentralize the city’s public schools, let alone the full vision of community control championed by those at Ocean Hill-Brownsville.

Polarizing the city along racial, class and ethnic lines - the strike shortening the ideological and cultural chasm between Jews and New York City’s other white ethnic communities, as “continued Jewish ambivalence to ‘white’ identity became impossible.” This sentiment of shared racial identity was borne on the picket lines outside of J.H.S. 271, the epicenter of the conflict, where “Catholic policemen, long viewed with suspicion in the Jewish community, were now the teachers’ protectors from hostile blacks.”

A noticeable split - between religiosity, age, and class - amongst New York City’s Jewish community had taken hold: “It is perfectly clear that by mid-1969 in New York City, much of the city’s traditionally accepted feelings for Blacks as underdogs has eroded and even disappeared.” (pollster Louis Harris)

Enjoying the piece? Help me reach new readers by sharing on Twitter !

“[John Lindsay] has labored heroically to communicate with the Blacks in the ghettos. The city has had no major racial upheaval since 1964. Yet many white New Yorkers feel neglected as a result. In huge areas of The Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, thousands feel that Lindsay is interested only in the Black and Spanish-speaking slums.” (TIME)

The white ethnic backlash against the CCRB foreshadowed a conservative wave on the horizon against Gotham’s White Knight - as the counterculture which had dominated the decade gave rise to the aggrieved “Middle Americans” - Time magazine’s 1969 Man and Woman of the Year - a “silent majority” who resented attacks (welfare, pornography, drugs, crime, protest culture, militancy) on their middle-class values, and increasingly felt ignored by coastal elites.

New York City’s “Middle Americans - German, Irish, Italian, Polish, Greek, and Jewish immigrants who were either civil servants (teachers, fireman, policeman), union members (welders, electricians, carpenters), or members of the petit bourgeoisie (clerks, accountants, small businessmen)” - quickly developed a collective animosity towards John Lindsay.

Nonetheless, the Mayor declined to pursue appointment to fill New York State’s vacant Senate seat following the death of Bobby Kennedy, unwilling to abandon his crusade as the leading voice for America’s cities. Had Lindsay returned to Washington D.C. as New York Senator, he would have preserved his broad popularity and assuredly better positioned himself for higher office in the future. Instead, his rising star was consumed by what many observers increasingly believed was an “Ungovernable City” - with many of the ills of the Wagner administration devolving during Lindsay’s tenure, leaving the new Mayor unable to shoulder the majority of the blame onto his predecessor.

Speaking of, Robert F. Wagner Jr. had grown increasingly restless in semi-political retirement. Despite living a comfortable life as the United States Ambassador to Spain, the son of New York’s former New Deal-era Senator had grown tired of Lindsay’s persistent attacks on his administration - vowing to make a political comeback to deliver City Hall back to the Democratic Party.

Yet, Wagner was not alone - as Democrats and Republicans alike sensed blood in the water.

Herman Badillo, the Puerto Rican Bronx Borough President, emerged as the liberal alternative to Wagner - striving to thread his own Rainbow coalition of Latinos, Blacks, and Manhattan liberals. Norman Mailer, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, was intent on shaking up the campaign with a unique brand of pseudo-urban populism that promised to decentralize all city services to the neighborhood level and make New York City the Fifty-First State. Community control - “compulsory free love in those neighborhoods which vote for it along with compulsory church attendance on Sunday for those neighborhoods who vote for that” quoted Mailer - would be taken to the extreme.

On the opposite end of the ideological spectrum sat New York City Comptroller Mario Procaccino, a conservative Democrat defined by the Italian-American neighborhoods in the Bronx which buoyed his rise. Born the son of a shoemaker in a small Italian town, Procaccino was described by journalists as “ethnic in extreme… unabashedly patriotic, a firm believer in ‘the Guy upstairs’ and a heavy-handed, unsophisticated, painfully sincere man.” While derided by the cosmopolitan class as the “frenetic voice of a reactionary Democratic bloc,” Procaccino held emotional cachet with crime-weary working-class white ethnics.

After receiving the Republican nomination uncontested four years earlier, Lindsay would not be so lucky this time around, as conservative State Senator John Marchi of Staten Island threatened to dethrone the sitting Mayor in the Republican Primary. The Republican electorate - approximately 30-40% Italian, 15% Irish, 15% German and only 5% Jewish - was a poor fit for Lindsay, to the point where his Campaign Manager, Robert Aurelio, urged the Mayor to forsake the primary and focus on the general election - only for the idea to be rebuffed by Lindsay’s financiers, the last vestiges of big-moneyed Northeastern liberal Republicanism.

Amidst the fight of his political life, Lindsay made a near-fatal mistake almost immediately. Caught off guard by fifteen inches of snow - the head of the Sanitation Department was out of town and 40% of the snow clearing equipment proved defective (owing to poor maintenance) - life in New York City froze for three days, culminating in forty-two deaths and hundreds of injuries. Queens bore the brunt of the damage, as rumors swirled that sanitationmen had purposefully neglected to plow the streets of the World’s Borough to exact revenge on Lindsay for his “behavior during the previous year’s strike.” If voters in the outer boroughs needed more fodder for the notion that Lindsay was increasingly out of touch with the pulse of their communities, the snowstorm debacle perfectly encapsulated the resentment that awaited Lindsay at the ballot box.

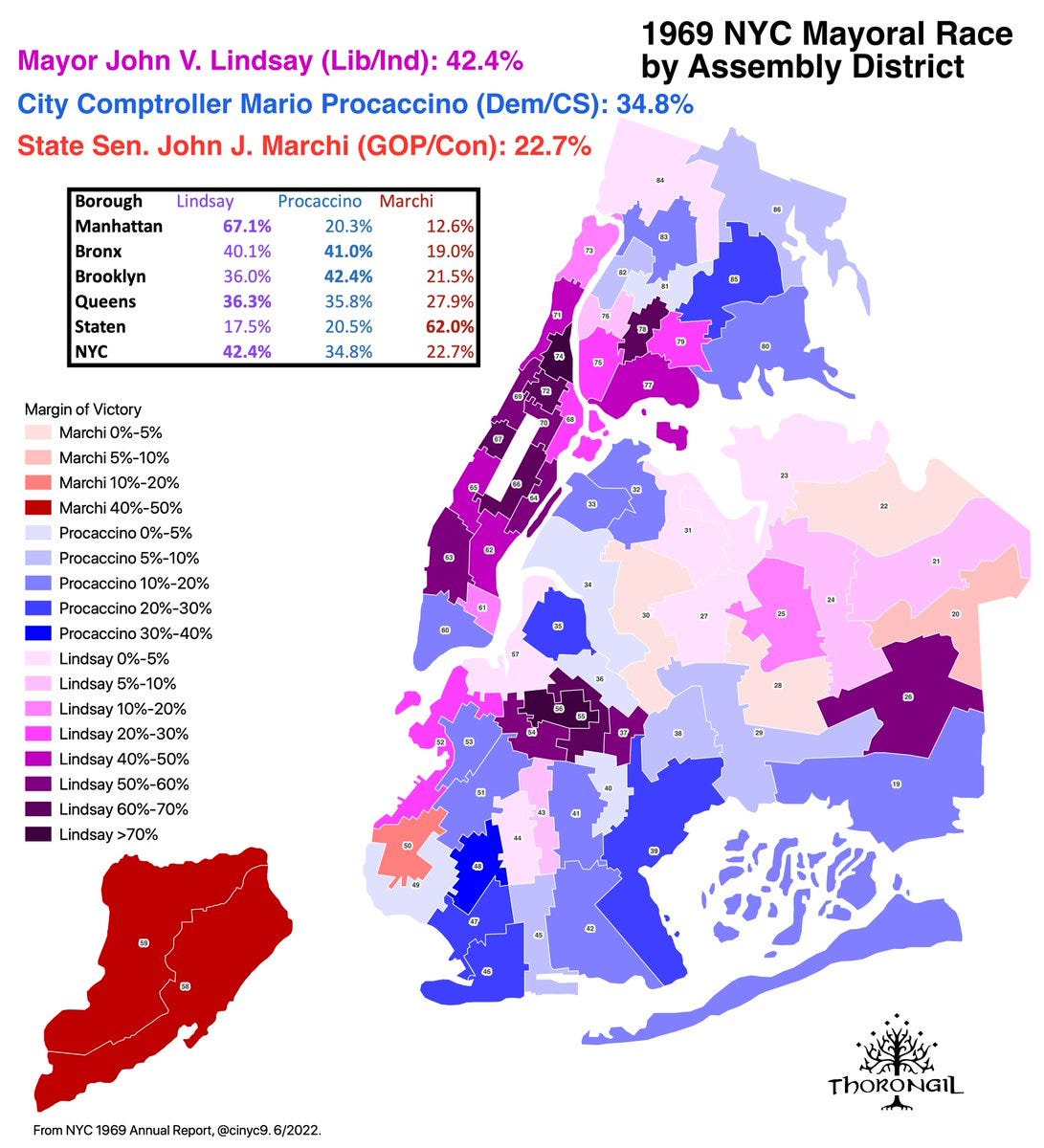

Despite running an “inept and lifeless campaign,” Marchi narrowly defeated the incumbent-Mayor - 113,000 votes to 107,000 in the Republican Primary. While Lindsay won his home borough of Manhattan with 78% of the vote - he lost countless middle-class Jewish neighborhoods that had backed him in 1965, like Riverdale, Forest Hills, Rego Park, Flatbush and Midwood - while being predictably crushed with Irish and Italian voters.

The Conservative backlash carried over to the Democratic Primary, where Procaccino bested both Wagner and Badillo - winning a plurality with a mere 33% of the Primary vote. Amidst a heavily-divided field, both Mailer and James Scheuer, a reform Congressman from the Bronx, siphoned off countless liberal voters that ultimately denied Badillo first place. Wagner, solely focused on settling his personal score against Lindsay, failed to effectively contrast himself with his Democratic counterparts - while struggling to weather criticisms that his three terms had contributed to the city’s decline. Winning 67% of the Italian vote, Procaccino ran up heavy margins among his ethnic brethren, particularly in Bensonhurst, South Ozone Park, Howard Beach, and his base in the East Bronx.

Across both primaries, pollster Louis Harris detailed, “at the heart of the Lindsay and Badillo vote were the young people and affluent voters, along with Blacks and Puerto Ricans.” Indeed, both Lindsay and Badillo won virtually every Assembly District in Manhattan, not to mention every Black or Puerto Rican district throughout the City.

Marchi and Procaccino thrived amongst older, less-educated voters - dominating the Italian electorate in both parties. In the razor-thin Democratic Primary, the splintering of the Jewish vote - Wagner 37% Procaccino 27% Badillo 22% - proved decisive in shaping the outcome, as Procaccino performed better than expected, winning Borough Park, Riverdale, Midwood, Flatbush, and Sheepshead Bay.

Facing his first electoral defeat, Lindsay would nonetheless have a chance at redemption in Noevember’s General Election - for he had secured the backing of the Liberal Party. No longer tethered to the Republican Party, Lindsay’s coalition of liberals, Blacks and Puerto Ricans - which had thus far been defeated thrice at the ballot box (1966 CCRB referendum, both ‘69 Lindsay and Badillo’s primaries) - became the Mayor’s only hope of securing a second term.

“Reaction is the order of the day and liberalism is in retreat.”

Procaccino’s unexpected triumph brought disarray upon New York City’s Democrats - particularly amongst the party’s liberal intelligentsia - who were not fond of the eccentric Italian at the top of the ticket.

Congressman Hugh Carey, who later served as New York Governor, called the election, “a real Hobson’s choice - an incompetent liberal Republican, an inexperienced conservative Republican, and an unimaginative conservative Democrat.” Carey himself, despite falling short of winning the Democratic nomination for City Council President by just 0.3%, refused to request a recount - terrified by the chance he could actually win the primary, and thus be forced to share a ticket with Procaccino.

No longer inhibited by the Republican Party - John Lindsay was eager to exploit the divisions in the Democratic Party and fill the liberal vacuum. Swiftly, prominent reform Democrats began defecting from their party to endorse Lindsay - including the highly-influential New Democratic Coalition, the liberal bedrock of Manhattan’s Upper West Side that was founded by former aides to Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy.

Herman Badillo, who won 88% of the Puerto Rican vote and 53% of the vote in the Democratic Primary, and Brooklyn Congressman Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to the House of Representatives, both endorsed Lindsay. Democratic City Council Member J. Raymond Jones, the powerful “Harlem Fox” - a longtime ally of Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and former head of Tammany Hall - condemned the Procaccino campaign as “antiblack’” and backed Lindsay. The endorsements of Badillo, Chisholm and Jones laid the groundwork for the most potent Black-Latino electoral coalition up to that point in New York City history.

Nonetheless, a lionshare of the Democratic establishment stuck with Procaccino - particularly, the county organizations in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. Despite having two conservative Italians on the ballot, in reality, Procaccino and Marchi could not have proven more different.

“Marchi, born and raised in Staten Island, was the son of an Italian immigrant from the Tuscan town of Lucca in northern Italy. His father was a sculptor who made movie sets in Hollywood before moving to Staten Island and starting a company that manufactured fruit wax. Many Italians thought Marchi (pronounced: Markey) was Irish, not Italian. Marchi was fluent in standard Italian, but that did him little good when he was campaigning in New York’s Italian neighborhoods, where most Italian speakers spoke a dialect that bore little resemblance to standard Italian. He was a northern Italian among New York’s heavily southern Italian population - living in the bucolic Ward Hill section of Staten Island, miles away from the mean streets of Brooklyn or the Bronx. In some ways, Marchi was as foreign to most ethnic New Yorkers as Lindsay.” (Cannato, Ungovernable City)

Editor’s Note: Remember PBA leader John Cassese from the CCRB referendum? The guy who was shelved from the anti-CCRB efforts because of his racially-charged language. He quit his job to work for Procaccino

Ultimately, the uninspiring Marchi proved little threat to Procaccino - who was content to self-immolate all on his own. Despite holding an early lead, Procaccino frequently unraveled on the campaign trail, launching into emotionally-charged tirades. The Bronx Democrat remarked that his running mate, Francis X. Smith, “grows on you like cancer.” Addressing a Black audience, his appeal - “my heart is as Black as yours'' - backfired spectacularly. Procaccino repeatedly embellished his resume - the most amusing of which was his claim that he was the President of Verrazano College (it did not exist). Contrasted to Lindsay by the media at every turn, an insecurity swiftly consumed Procaccino, to the point where he carried around a copy of his law school transcript to show reporters. When the Daily News released a poll late in the race showing the Bronx Democrat twenty-points behind Lindsay, which subsequently doomed his already-weak fundraising - Procaccino proceeded to sue the paper. Unsurprisingly, the campaign was a one-man show - with Procaccino “writing or rewriting all his speeches, doing his own scheduling, and distributing his campaign literature.” Relying on the atrophying Bronx Democratic Machine, Procaccino resorted to his own instincts, which became a “one-note denunciation of crime.”

Editor’s Note: On a scale from 1 (Tish James at her Public Advocate Inauguration) to 10 (literally George Santos) on the Lie scale - Procaccino’s foibles are probably a 5.5

In spite of these episodes, Procaccino remained a proficient retail-campaigner who resonated with blue-collar whites. Procaccino called Lindsay “the actor,” famously coining the term “limousine liberal” to define the cultural chasm between the middle-class of the outer boroughs and their affluent Manhattan counterparts. Middle-class whites, estranged from Lindsay’s world of cosmopolitan culture, private schools, fund-raising galas, doormen, and trips to the opera - shared Procaccino’s ire. Yet, Lindsay’s team successfully portrayed Procaccino as a caricature of himself, tactics that (in many instances) resembled anti-Italian prejudice, but nonetheless significantly diminished his stature amongst the broader electorate.

While much of the Mayor’s aurora, in the past so instrumental to Lindsay’s image, had faded by 1969 - the liberal White Knight proved capable of running a smarter campaign than four years prior. With few accomplishments to tout - save for air conditioning the subways, balancing the budget, and reducing sulfur-dioxide pollution - Lindsay leaned into humility, emphasizing how difficult it is to effectively govern New York City, calling it the “second-toughest job in America,” while taking greater advantage of television ads to exploit his physical advantages. Lindsay admonished the war in Vietnam, vowed to take on landlords, and humbly admitted (most of) his mistakes in his defining television ad.

The New York Times Editorial Board endorsed Lindsay not once, but twice - lauding him as an “activist mayor” who reached out to Black and Puerto Rican communities. The New York Post, Amsterdam News, and Village Voice backed the candidate of the Liberal Party as well. Organized labor, which had eschewed Lindsay in ‘65, now rallied to support the Mayor - a surprising development given the many tense strikes that headlined his first term, but the result of a short-lived “marriage of convenience” that saw Lindsay approve generous public employee raises that staved off future strikes. Even Albert Shanker and the UFT remained neutral.

Jewish voters, once again the vital swing electorate in a close race, were intensely courted by Lindsay. When Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir visited the City in the fall of 1969, the Mayor’s aides arranged a dinner in Meir’s honor at the Brooklyn Museum, before insisting on building a sukkah (“a tentlike structure where religious Jews could eat during religious holidays) as a gesture to Meir and the City’s Orthodox Jewish communities, so the celebration could be held outside in commensurate with the Jewish holiday of Sukkoth (The Festival of Tabernacles). With the help of the Lubavitcher and Satmar sects of Hasidim, the sukkah was built, and Golda Meir agreed to attend the twelve-hundred person event - signaling to many attuned voters that “the Israeli interest is to have John Lindsay as Mayor.”

Not only was the electorate shifting, the manner in which political campaigns were run was also changing. Lindsay’s campaign, through their use of television, canvassing, and polling - symbolized the era of “New Politics” - whereas Procaccino’s campaign was rooted in the past, reliant on political bosses past their prime and increasingly outflanked in the press - failing to receive a single major media endorsement. Columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak called Proaccino’s effort, “the most inept Democratic Mayoral campaign in modern history.”

Once more, John Lindsay prevailed with a plurality of the vote (41.1%), comfortably finishing ahead of Procaccino (33.8%) and Marchi (22.1%) - calling his triumph, “a commitment by the City as a whole to progressive government.” Lindsay had achieved the greatest third-party performance in New York City’s modern history, a feat praised by The Nation and considered the crowning achievement of the Liberal Party.

Lindsay took over two-thirds of the vote in Manhattan, while carrying every Black and Puerto Rican Assembly District - finishing with 85% of the Black vote, 65% of the Puerto Rican vote, and 45% of the Jewish vote. Young voters, from students to reform-minded professionals, increasingly left-leaning and catalyzed by the Vietnam War, spearheading Lindsay’s volunteer operation - becoming a formidable voting bloc in their own right.

Middle-class Jewish districts, like Riverdale, Washington Heights, Forest Hills, Flatbush and Midwood - which had backed Lindsay in ‘65, voted against his CCRB referendum in ‘66, and eschewed both him and Herman Badillo in the ‘69 primaries - delivered pluralities to the liberal Mayor in the 1969 General Election.

Procaccino, who later asserted that the election was stolen, also won 45% of the Jewish vote, in addition to 60% of the Italian vote - performing best in the “heavily-Italian northern and eastern sections of the Bronx and the working-class Italian and Jewish neighborhoods of Southern Brooklyn.” In the first municipal election since the Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike, a significant share of outer-borough Jews had backed Procaccino, foreshadowing the realignment that would shape the next three decades of New York City politics.

By coalescing upper-middle class liberals, young progressives, Blacks, and Latinos - John Lindsay forged a first-of-its kind winning progressive coalition in New York City - that would later be replicated (to varying degrees) by Jesse Jackson and David Dinkins. However, the seeds for Ed Koch’s more moderate, Jewish-Catholic coalition had been planted.

John Lindsay’s victory on the Liberal Party line marked the unofficial end of his tenure as a Republican. While the Mayor had remained at arms-length with his party since his controversial snub of Barry Goldwater in ‘64, the beginning-of-the-end came when the likes of President Richard Nixon and Governor Nelson Rockefeller declined to aid Lindsay amidst the heated ‘69 Republican primary, only to promptly endorse John Marchi in the general.

Lindsay’s public break with Rockefeller, traditionally an ideological ally within the party, was more representative of competing egos and personal animosity - yet, the move obscured how the Republican Party, both nationally and throughout New York State, was becoming more conservative. Rockefeller, while not a close friend of the Mayor, remained exponentially more hospitable to his liberal tendencies than the likes of Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon, and Barry Goldwater - the figures who would ultimately chart the party’s future course. The New York Young Republicans, where a young Lindsay had cut his teeth campaigning for Thomas Dewey and Dwight Eisenhower, came to resent their high-profile alumna:

“These were no longer the young prep school and Ivy League types with whom Lindsay had associated during the 1950’s. It was a new breed of hard-edged, conservative young Republicans who had been seared by the events of the 1960’s. Lindsay was even less at home with them than he was with Nixon and Rockefeller.” (Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

Unsurprisingly, Lindsay officially switched to the Democratic Party early in his second term. Cutting himself off from his powerful financiers, the fraternal vestiges of Northeastern liberal Republicanism, Lindsay was left to cozy up to the Democratic Party bosses in the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn that he had once so vociferously campaigned against. Greeted with skepticism by many party regulars, the Mayor’s move was nonetheless overdue, serving as a precursor to Lindsay’s rumored interest in seeking the Democratic nomination for President in 1972.

Despite an expressed desire to avoid the bruising battles that defined his first term, Lindsay’s grand ambitions would ultimately be derailed - as the threads which fastened his delicate 1969 coalition slowly came undone amidst “The Battle for Forest Hills.”

For much of the post-WWII era of urban renewal, city planners were content to solely build public housing in low-income neighborhoods, often in the form of large “self-contained” projects that were effectively “super-imposed” on the community itself - urban planning which further perpetuated segregation and poverty. In contrast, the Lindsay administration had vowed to build low-income, “scatter-site” housing throughout many middle class enclaves - a “moral imperative” designed to both integrate the city’s neighborhoods while simultaneously raising the quality of life for public housing residents.

However, the project did not break ground until 1971, finally doing so in the lush, middle-class Queens neighborhood of Forest Hills, whose housing stock oscillated between high-rise developments and Tudor-style single family homes - with the three twenty-four-story buildings of low-income housing slated for a vacant site adjacent to the Long Island Expressway.

While Lindsay predicted that scatter-site housing would elicit backlash, he thought the project would fare better in a “liberal” neighborhood. Although Forest Hills had supported both of his campaigns, many of the neighborhood’s middle-class Jews had moved there from Brownsville, Crown Heights, Williamsburg, East New York, Hunts Point, and Far Rockaway - in an attempt to “to keep themselves one step ahead of social decay… [all while] the Lindsay Administration kept narrowing the gap.”

Opposition to the development was overwhelming, as community members formed the Forest Hills Resident Association, with protesters castigated the Mayor at every turn - holding signs ranging from “DOWN WITH ADOLF LINDSAY”, “SAVE MIDDLE CLASS AMERICA” to “LINDSAY IS TRYING TO DESTROY QUEENS, NOW QUEENS WILL DESTROY LINDSAY”.

“Many Forest Hills residents were the children or grandchildren of immigrants and had grown up in poor New York neighborhoods. Jerry Birbach, the spokesman for the Forest Hills Resident Association, epitomized the social background of Forest Hills. He grew up poor in Williamsburg, went to City College at night for his degree, and built up a real estate business in Manhattan. [The middle-class residents of Forest Hills] believed the city was giving the poor a place in their neighborhood without making them work for it.” (Cannato, Ungovernable City)

Whereas the social strife in Forest Hills was primarily viewed through a racial lens - the rejections of scatter-site housing from other middle-class communities throughout Queens, from whites in Lindenwood to Blacks in Baisley Park, underscores the preeminent role that class played in shaping attitudes towards housing.

Would 840 housing units - earmarked for low-income and elderly families - drastically change the “character”, alter the “middle-class values”, or compromise the school system of a neighborhood that was ninety-seven percent white, and totalled over 150,000 people?

But, the project - as originally designed - never came to fruition. Faced with an increasingly contentious environment, City Hall tasked lawyer Mario Cuomo (yes, that guy) with mediating a compromise between all parties, culminating in a recommendation that the proposed development be halved - resulting in three, twelve-story buildings totaling 432 units, 40% of which would be designed exclusively for seniors. After months of insisting the development would not be altered - Lindsay conceded to Cuomo’s recommendation, eager to put the draining battle behind him. Birbach, the chief anti-development spokesman, predictably blasted the compromise - but privately phoned Cuomo to admit he never read his proposal. Soon after, the housing development was turned into a co-op at the behest of Queens Borough President Donald Manes, who sought to “improve the quality of potential tenants” - with residents required to pay “shares” (although they could not sell to anyone except NYCHA), a maintenance fee, and meet a higher income threshold than most public housing residents.

In the end, after years of fear mongering and racially-charged rhetoric, the development had become nothing more than a “predominantly white co-op for the working poor and elderly.” Forest Hills did not suffer the demise many predicted, and remains a leafy middle-class enclave to this very day. The reactionary residents who fled following the development’s completion were swiftly replaced with Jewish immigrants from Russia and Israel - “thus retaining the neighborhood's religious character”.

Yet, John Lindsay was never vindicated. Instead, the development debacle helped fuel the rise of Ed Koch - a prominent critic of the Mayor - who was content to exploit racial and class fissures throughout the five boroughs to construct his own Citywide electoral coalition. Before Forest Hills, the Manhattan Congressman - who succeeded Lindsay in the Silk-Stocking district - was regarded as a proud liberal reformer. Nonetheless, Koch, whether by cold-blooded political calculation or his own personal deviation, came to vehemently oppose the project: “I believe that three twenty-four-story buildings with 4,500 people on welfare inserted into a middle-class area would destroy the [neighborhood].”

Koch credited his opposition to the Forest Hills development as the turning point of his political career: “[Forest] Hills did more to distinguish me among New Yorkers than anything I ever did on the House floor. It allowed me to persuade people I was not some crazed Greenwich Village liberal.” The move became integral to Koch building his reputation as “a liberal with sanity,” endearing him to the white middle-class, and paving his path to City Hall.

While John Lindsay’s coalition reflected the liberal politics of the 1960’s - liberals sensitive to police brutality and the precarious conditions pervasive throughout low-income neighborhoods, youths emboldened by student protest politics and radicalized by the Vietnam War, and Blacks and Puerto Ricans too often marginalized by government - Ed Koch sat at the vanguard of New York City’s next political realignment, which echoed the retrenchment of the 1970’s.

Koch had little interest in making overtures to the City’s racial minorities, for he did not need their votes to be elected. Rather, he married his traditionally liberal base in Manhattan with the more conservative white ethnic population of the outer boroughs - the majority of whom had come to despise John Lindsay. Unhesistant to malign low-income communities as either criminals or fully-dependent upon welfare, Koch siphoned off some support from middle-class Blacks and Latinos as well. For many of these residents, John Lindsay would never be forgotten for walking the streets of Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, East New York, and the South Bronx during many tension-filled summer nights - nor did his efforts to decentralize public schools, build low-income housing, open admission at CUNY, and reign in police brutality, come in vain - yet, Lindsay could not escape that during the eight years of his tenure, living conditions throughout five boroughs, particularly among the city’s least-fortunate residents, deteriorated considerably.

However, the most significant shift in New York City’s electorate from Lindsay to Koch came from the Jewish vote at large. Lindsay had barely held together his delicate progressive coalition in 1969, and the racial and class polarization that lingered following Ocean Hill-Brownsville and Forest Hills foreshadowed its impending fracture. Jewish voters, from Manhattan’s Upper West Side to the Riverdale section of the Bronx - many of whom twice voted for John Lindsay - became the bedrock of Ed Koch’s three terms as Mayor. As the calamity that consumed the Lindsay administration cascaded into the following decade, capped off by a rapidly evolving fiscal crisis - pundits proclaimed that “liberalism was dead”. During such a tumultuous period, even liberal Jews, traditionally ideologically distanced from the Irish, Italians, and Germans - eschewed more left-leaning Democrats like Bella Abzug, Percy Sutton, and Herman Badillo who sought to replicate Lindsay’s ‘69 coalition. Koch’s ascension to City Hall (following a four year, post-Lindsay flirtation with Abe Beame), where he campaigned repeatedly on reinstating the death penalty (a state issue nonetheless), underscored this current. While other major cities around the country elected liberal mayors with reform, multiracial coalitions - Koch slowly consolidated New York City’s white electorate.

Thus, when New York City’s fiscal crisis came to a head during the mid-1970s and city leaders slashed municipal services at the behest of a financial control board, it was working class Blacks and Latinos — already the city’s most vulnerable residents — who were left to suffer under New York City’s embrace of austerity.

In the years that followed, there would be little talk of Rainbow Coalitions in New York City.

So, what happened to John Lindsay?

During his ill-fated and unexceptional run for the Democratic nomination in 1972, Lindsay spoke frequently of the urban problems he cared so deeply about. If only he could convince the rest of the country to care as much as he did. Yet, upon his swift rejection by the Primary electorate, Lindsay humbly returned home to New York City, his political career over.

Weathered and worn, with the toll of eight years in City Hall catching up to the Mayor - Lindsay followed the counsel of his aides and decided to not seek re-election for a third term, in what likely would have ended in another humiliating defeat.

Rejected by Republicans and ignored by Democrats, Lindsay retreated from political life following his departure from City Hall. Blamed by his predecessors, Abe Beame and Ed Koch, for New York’s fiscal meltdown, Lindsay remained bitter, hurt, and depressed. New York Times Magazine dubbed Lindsay, “An Exile in his Own City.”

Lindsay’s curtain call came in 1980 - when he launched a longshot bid to be New York’s Democratic-nominee for Senate. Liberal voters throughout Manhattan, the core of Lindsay’s support for nearly two decades, had moved on from the ex-Mayor - preferring the likes of Elizabeth Holtzman and Bess Myerson instead. Ultimately, Lindsay took less than fifteen percent of the vote in his former Silk-Stocking district, and twenty-percent of the vote in Manhattan at-large, stumbling to a distant third place finish.

“Missing was the soaring rhetoric of his first term as Mayor. The man who ran for President in 1972 to put the problems of cities on the national agenda said very little about cities during his 1980 Senate race.” (Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

The man who published hundreds of position papers when he vied for Mayor, now ran a largely issueless campaign. Gone were the big money financiers, as well as his former staff members - many of whom, like Holtzman and Myerson, had evidently moved on to bigger and better things. The aurora that once captured the hearts and minds of New Yorkers everywhere was fleeting. All that was remained was John Lindsay’s quest for redemption.

Fittingly, Lindsay’s best performances all came in Black and Latino neighborhoods like “Harlem, Springfield Gardens, the South Bronx, East New York, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville, Bushwick and Ocean Hill.”

In spite of his diminished reputation - there was still plenty of goodwill left in New York’s City communities of color for John Lindsay.

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com