Michael Kenneth Williams and the Power of Humanity

How Brooklyn nurtured a timeless legend

“Michael has made people think twice about a world of men that we pass by or don’t know about. He has opened up a window of reflection to people who see folks on the corner that they may have never given humanity to.”

On September 6th, Michael Kenneth Williams tragically passed away at the tender age of 54.

News of Michael’s death rippled throughout the currents of our society. While the volume of tributes was staggering, Michael’s impact transcended testimonials. He possessed the rare ability to bring joy to millions through his talent, leaving a lasting impression matched by few others. But Michael’s greatest gift, as Wendell Pierce, a co-star of his on The Wire, articulated above, was his ability to engender compassion and empathy for his characters on screen, many of whom were Black men on the margins of society.

Michael’s roots and experiences in Brooklyn, from the housing projects of East Flatbush to his penthouse in Williamsburg, remained central to his identity, serving as an integral influence not only on his acting career, but more importantly, his development as a man.

Michael’s arch, evolution, and struggles are intertwined with the borough he has always called home. His relationship to the City and its people - and how such a bond shaped his life - is essential to understanding the sensitive man who captured our hearts and minds.

“Veer, although there was a lot of violence growing up back then, I wouldn’t trade my childhood for anything. Scars seen and unseen made me the man I am today.”

Michael’s upbringing orbited the Vanderveer Estates, a collection of 59 red-brick buildings, six floors high, with seven apartments per level spread across 30 acres in East Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Bounded by Nostrand Avenue to the west and Newkirk Avenue to the north, Vanderveer Estates takes up four city blocks and is divided across Foster Avenue. Vanderveer is one of the largest privately owned rent-stabilized low-income developments in the City, annually housing 7,000 of East Flatbush’s working class since 1949. The development has seen a revolving door of ownership during the past half century, marred by thousands of housing code violations and a legacy of crime and drug use.

Vanderveer residents nicknamed the drug corner at the intersection of Nostrand and Foster “the Front Page” because killings there received greater media attention, often landing on the front pages of the local newspapers. Meanwhile, the southern and eastern corners of the complex, near Brooklyn Avenue, were called “the Back Pages”, as the murders there went unnoticed by the press. For decades, many “entrenched highly organized drug-distribution operations” ran through Vanderveer, drawing significant attention from the NYPD’s 67th precinct, which, at times, has attributed as much as 40% of the total crime in East Flatbush to the development.

Michael’s birth in 1966 coincided with East Flatbush experiencing an exodus of white residents at the onset of New York City’s fiscal crisis before the subsequent erosion of social services. As Italian, Irish, and Jewish residents relocated, Afro-Caribbean immigrants from the West Indies filled the vacuum, coming from Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Trinidad, Grenada, St. Vincent, Barbados, Panama, and the Dominican Republic.

Today, East Flatbush is the single largest West Indian neighborhood in all of America.

With its combination of Afro-Caribbeans and African Americans, East Flatbush became the Blackest neighborhood in the City, which is still true today. Michael’s family mirrored the intersection between Black Caribbeans and Black Americans, as his mother, Paula, immigrated from Nassua, Bahamas, while his father, Booker T. Williams, was raised in Greeleyville, South Carolina - a small, majority Black town of less than 400.

“My father being Black American and my mother from the Bahamas, let my hood tell it and I may as well have been bi-racial.”

Growing up, Michael’s mother was his biggest influence, especially after his father left the family when he was a teenager. She was determined to steer Michael so he avoided a harsh fate that beset many other Black youth in Vanderveer:

“My mother was extremely strict, she had strong views on how a young man should act and behave. This was very different from what was happening just outside my door. I was not allowed to fight for any reason, not even to defend myself, the rule was my mother was the end all that be all in authority.”

Michael’s love for community can be traced back to his mother, who founded a daycare center in two vacant offices in the building’s lobby. Not only did Mrs. Williams pay for the space out of pocket, but she redid it completely, beautifying the office and lobby with plants, pictures and mirrors. She named the daycare center “Morning Glory” which was hailed as a godsend to young mothers who Mrs. Williams mentored, and their children. Michael reflects with great pride that his mother made the most of everything she was given, and did the absolute best she could for him:

“It was hard for a Black woman raising a Black boy in an aggressively violent neighborhood. That was not easy to navigate through alone. But my mom is so stable, so grounded, such a foundation. She created such a foundation for me in the middle of the jungle. As I remember these things it makes me love her even more for it.”

But elsewhere, Michael felt a lack of empathy. His presence was noticed, but his humanity was not. Even at a young age, Michael became painfully aware of the power dynamics and the intersections between race and class that permeated throughout his every interaction. A particular experience involving the Hasidic Jews who owned Vanderveer resonated with him forever:

“I remember my mother would have me go down to the rental office to give them her hard earned cash for rent. I remember the fluorescent lights making their white skin look that much whiter, me coming in there with my dark skin was such a distinct contrast. I remember having to navigate the envelope to their hand because they wouldn’t make eye contact with me. Between them and the cops, I always wondered why the people with the power never looked like me.”

Throughout Michael’s adolescence he felt powerless when confronted by adults, who used their authority to manipulate his insecurities. Such misery crystalized when Michael was sexually molested as a teenager, which spurred a deluge of confusion. Michael’s disillusionment with life increased, leading him to withdraw from his peers to cope with the agony.

While his trauma was kept silent, Michael’s vulnerability only grew, making him an easy target. Suddenly, Michael was not only mistreated by adults, but by his peers - who mocked, bullied, and tormented him, calling him names like “Blackie” and “Faggot Mike”.

His sensitivity was exploited and his tenderness was weaponized against him, leaving lasting internal scars and dampening his spirit. Lacking any positive male role models, Michael was eager for a sense of belonging, but his efforts were futile. Throughout his young adulthood, he bounced in and out of drug clinics while getting busted for stealing cars and committing credit card fraud.

Consumed by insecurity and struggling to fit in with the bruising nature of Vanderveer’s everyday life, Mike found a home dancing in Lower Manhattan’s gay nightclubs. Michael, free and unencumbered, began to feel comfortable in his skin. His talent as a dancer was profound, almost undeniable, and ultimately landed him roles in music videos and on the tours of Madonna and George Michael. But more importantly, Michael relished the lack of judgement the gay community afforded him.

Michael’s lived experiences, from the Vanderveer Projects to the gay bars of Lower Manhattan, gave him unique insight into two of New York City’s most marginalized communities: young Black men and homosexuals. Michael cherished the humanity of his neighbors at Vanderveer, many of whom were branded as a lost cause, and his gay friends on the dance floor, who were antagonized by the government and castigated by the general public for their lifestyle.

Such proximity to marginalization helped Michael redefine narratives around gay Black characters, which led him to deliver the defining performance of his career: Omar Little on HBO’s The Wire.

At the time, colorism and type casting had plagued Black actors while homophobia was rampant not only on the screen, but throughout writers rooms and casting departments. Michael, by being cast as Omar, was confronting issues of Black masculinity in conjunction with the prevailing racism and homophobia at the time.

“It’s impossible to stress how big a risk he took when he agreed to play Omar. If media images of straight Black men were limiting, Black gay roles were radioactive. Pre-Omar, gay, Black, and male meant squealing caricatures (In Living Color’s Blaine Edwards and Antoine Merriweather) and gossipy hairdressers (Soul Food).* In “real” life, there was author J.L. King on Oprah, dishing about deceitful gay Black men living “on the down low.” There were urban legends of Black gay men maliciously “spreading AIDS” to unsuspecting straight women, Black pulpits spewing violent sin-talk, and then–shock jock Wendy Williams whipping up hysteria with her hunt for “the gay rapper.” (Vulture)

Even though Michael did not identify as gay, he approached the role, knowing the power it held, with tremendous care and respect. With every interview or off-hand quote, Michael never shied away from confronting themes of sexuality and masculinity, doing so with a grace and awareness that few possess.

Michael’s ethos - that embracing the character of Omar through humanity, dignity, and honesty would help shift narratives on Blackness, masculinity and sexuality - proved true, as he actively sought to dispel stigma about homosexuality within the Black community:

“I get a lot of love in the ’hood, they love the honesty of my character. It makes them realize there are all kinds of people in the ‘hood.”

The Wire itself, which debuted in 2002 and concluded in 2008, is a master depiction of the systemic problems that plague Baltimore, from the working class whites to the Black youth on West Baltimore’s drug corners, while skillfully indicting the political, educational, and media ecosystems of the city for their role in such calamity. Produced by David Simon and Ed Burns, The Wire illustrated that crime and violence, which had often been characterized in media as Black issues, were not rooted in race, but class, and were the result of failed institutions, not individuals. Burns and Simon, who between them had decades of knowledge and experience confronting Baltimore’s dysfunctional establishment, created a world that paralleled reality, with a realistic, humanity driven depiction of Baltimore’s environment that challenged many of the pervasive narratives that had dominated TV depictions of inner cities.

When the show pivoted from the War on Drugs in West Baltimore in Season One to the economic anxiety of the white working class dock-workers of Season Two, Michael challenged the writing crew on such a drastic shift. While Michael was losing lines as Omar, his gripes weren’t centered on a reduced role, but on the overall direction of the show. Michael pressed Burns and Simon: “I’m saying, there are all these shows on television, and we made the one that was about Black characters and written for a Black audience. And now, it’s like we’re walking away from that.”

The show's writers had a unique responsibility to uphold their status as a Black-majority drama in the White world of television. After much discussion, Simon and Burns delivered a thoughtful answer: “If we do this season, we also make clear going forward that the drug culture is not a racial pathology, it’s about economics and the collapse of the working class — Black and white both. We want to have a bigger argument about what has gone wrong. Not just in Baltimore, but elsewhere, too.”

Such became a ritual, that, at the beginning of each season, Michael would ask the writers, “What are we going to say this year?” as part of an ongoing conversation around the deeper meanings of The Wire and how Michael could distinguish such a message.

The world of The Wire was not merely confined to Baltimore, as its themes echoed throughout the fabric of American society: “There is a Wire in every city in every state in the goddamn country”

Omar was an outlier in this world. An openly gay, shotgun-toting stickup man governed by his own sense of righteousness, he transcended the realism that bounded The Wire, achieving mythical status from the audience and his peers. In the universe of The Wire, Omar was feared without exception - the mere mention of his name spurred drug dealers to hand over their stash, terrified of a confrontation. He was not merely a thorn in the side of Baltimore’s drug kingpins: Avon Barksdale, Stringer Bell, and Marlo Stanfield - but a one man army capable of unraveling their entire organization. Omar’s power was not guaranteed by an advanced degree or an officer’s badge, nor could it be found in the court of law or in a police precinct; rather, it was on the street, where it had been earned.

Yet what made Omar a maverick was not solely his reputation on the street, but the loyalty, tenderness, honor, and sensitivity he carried himself with. Omar replaced allegiance to a crew or an organization with a strict adherence to a moral code - to never put his gun on someone “outside the game”. In spite of his “hard” reputation, Omar was never afraid to express his vulnerability or his sexuality, and, whether mourning the death of his loved ones or holding them tight, he did so on his own terms.

Omar forced viewers to reckon with moral relativism, the idea that there are no absolute rules to determine whether something is right or wrong. He stole, he lied, he killed. Yet, it never was that simple, as The Wire and most importantly, Michael, engendered empathy for Omar, daring the audience to consider the humanity and motivations behind such a man.

In many respects, Omar is The Wire’s version of a tragic hero.

Michael’s relationship to Omar was layered and complex. Out of all his portrayals, Michael said he related to Omar the most. On the surface, such a statement seems puzzling. Known for his timidness and quiet nature, how could Michael relate so deeply to a role characterized by grit and confidence? But it was not so simple. Michael loved Omar for his sensitivity, and that even in a cold, unforgiving world, he could still comfortably express his feelings. The raw emotions the audience witnesses in Omar are so poignant because Michael himself was acutely aware of the depth behind such feelings.

Not only did Michael see himself in Omar and The Wire’s many colorful characters, but he also saw his neighbors and friends at Vanderveer. To Michael, such figures were always larger than life and deserved to be portrayed as such. Michael always gave these folks humanity throughout his everyday life, thus it was only natural he extended such grace into his roles. Many scenes in The Wire could have taken place in Brooklyn and that connectedness helped Michael flourish in his role as Omar.

What is often missed in many reflections on the symmetry between Michael and Omar is that both were exceptionally brave. While their respective suffering was different, both were remarkably open and courageous about confronting despair, anguish, and loss. While Omar was unafraid to articulate the depth of his grief or break down in the face of immense despair, Michael consistently spoke with great clarity about his raw emotions, specifically his struggles with addiction and mental health. In a chaotic world, both sought to uphold a sense of order through expressions of morality.

While Michael was given tremendous recognition for the role of Omar (President Obama named The Wire his favorite TV show and Michael the show’s best actor), the elevation of the character came at a personal cost to him. Michael, who had struggled with drug addiction, was brought to a dark place while occupying the mind of Omar, as his character was plagued by his own suffering and anguish, which cascaded onto Michael.

The greater the attention that Michael’s depiction of Omar received, the more the lines between Michael and Omar became blurred, manifesting in an identity crisis. Omar became his “spider man suit”, as many folks began giving Michael respect because he was Omar, not because he was Michael.

Many would not even refer to him by name, just calling him “Omar” or just “O” - as if the role determined his status offscreen. Having been overlooked on the margins for years, Michael was well aware such attention was fleeting, which only furthered his disenchantment.

Unfortunately, more folks might remember the name Omar Little than Michael Kenneth Williams, but without Michael, Omar would have never existed as we knew. Michael was the only person who could have given such extraordinary life to Omar.

While Michael’s thoughtful and enduring portrayal of Omar helped humanize many oft overlooked individuals who struggle on society’s margins, it tragically stripped away parts of his own humanity in the process.

Michael, like Omar, is a tragic hero, bravely battling demons in pursuit of something greater than himself.

The Brooklyn that helped mold Michael has changed significantly since his childhood, mirroring his own personal growth. However, such progress is never linear, nor is it always upward sloping, which left Michael pondering whether he fit into the “new” Brooklyn.

The Vanderveer Estates, the backdrop of Michael’s youth, has changed ownership dozens of times, even being rebranded to Flatbush Gardens. Such an effort coincided with building management attempting to lure new tenants with higher credit scores and more stable sources of income. Such intentions are not exclusive to Vanderveer, or even East Flatbush, but have taken hold throughout the borough.

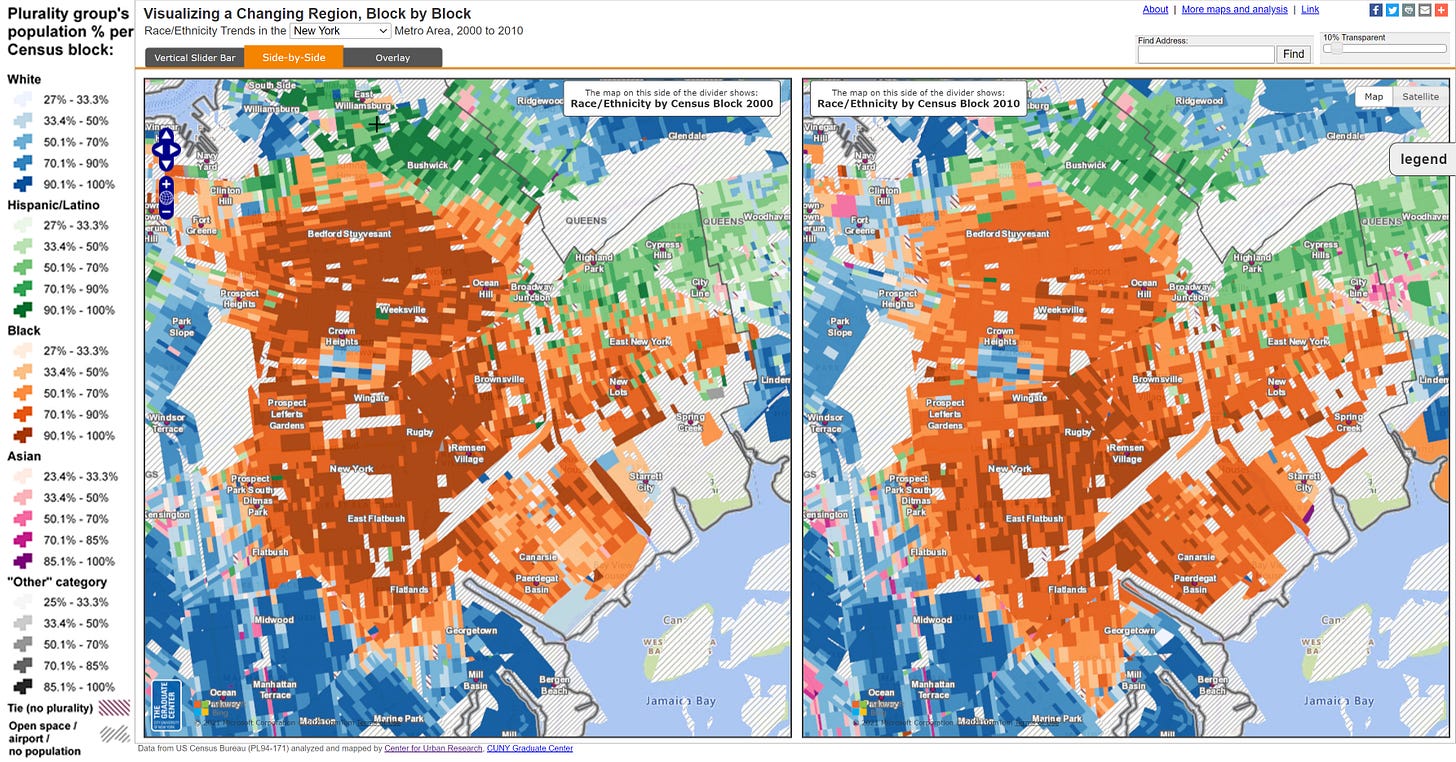

Over the last twenty years, Brooklyn itself has boomed, becoming a premier real estate destination resulting in a flood of rising rents and gentrification. Such sweeping changes have proven detrimental to the borough’s Black population, which have increasingly become displaced at greater numbers from neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant, Lefferts Gardens, and Crown Heights. In 2000, the Black population in Bedford-Stuyvesant was 75%; today, it has dropped precipitously to 45%. Such disturbing trends are evident elsewhere, as both the northern and southern portions of Crown Heights were approximately 78% Black at the turn of the century, but in the two decades since have dropped below 50%. Many of the African American and Afro-Caribeans displaced from Bedford-Stuyvesant and Crown Heights have relocated to East Flatbush, which has steadily maintained its Black population despite the sweeping tide of gentrification. While the long arm of development knows no bounds, many tenants, activists, and organizers that reside in East Flatbush are determined to keep the Black character of the neighborhood intact in the face of a hungry real estate industry.

Michael, who was evicted from Vanderveer in 2002 following a drug relapse, was nearly a victim of displacement himself. Throughout his time filming The Wire, Michael experienced prolonged housing insecurity which was linked to his active addiction. However, upon the show’s conclusion, Michael’s acting stock rose considerably, which helped him steadily secure roles for the duration of his career. Rather quickly, Michael found himself in an upwardly mobile economic position, not only able to afford to continue to live in Brooklyn, but anywhere he chose. Many of his peers at Vanderveer, and throughout Central Brooklyn, suffered a worse fate, which swelled him with guilt.

Michael bought a penthouse in the North Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg, an artisan landing pad in the 1990’s which was transitioning to a gentrifying hotbed at the turn of the new millennium. Such development was spurred by a large 2005 rezoning which converted many of North Brooklyn’s waterfront neighborhoods - once characterized by active manufacturing and other light industry interspersed with smaller residential buildings - into larger, high-density buildings for residential use. While newer tenants and celebrities flocked to the new housing units, the ripple effects were felt beyond the waterfront, as developers, despite tax breaks and incentives, failed to keep promises to build affordable housing, which displaced many long-term Puerto Rican residents.

Michael was caught up amidst these changes, and the dichotomy between the “old” Brooklyn and the “new” Brooklyn became the subject of great internal conflict within him:

“I’m a huge fan of how beautiful Brooklyn has become, but I do have an issue with the gentrification. I feel grateful that I’ve got a second chance at life, to be able to afford to live the way I do, coming from where I come from. But, it feels a little lonely. I don’t see a lot of blacks in Williamsburg at all.”

Michael lamented that in Williamsburg, despite his fortune and celebrity, he felt very out of place. Michael, who had grown up in a neighborhood with a thriving Black population of nearly 90%, was now living in an area where the said population did not eclipse 5%, which was reflected in how institutions interacted with the neighborhood:

“Sometimes, when I see, you know, antics on the weekend, I’d feel safer in the Vanderveer projects, where I grew up. I understand that kind of crazy. When I see the people in Williamsburg get crazy, I’m, like, O.K., where’s this going? If they were black, the police would probably be pouncing on them. I kind of just go in the house.”

These diverges were not just confined to policing, as the culture around drugs was radically different. This mirrored the world of television and Hollywood, where drug use was not only less stigmatized, but more normalized. Whereas back at Vanderveer, such behavior was not only criminalized, but villainized.

“Arresting people, or ruining people’s lives for a small, nonviolent charge, like marijuana, drug addiction, or mental illness, is not the way to go. Those are health issues, not criminal issues. It’s the grace of God that I wasn’t imprisoned for my antics growing up.”

Michael wondered whether the humanity shown to him with respect to his addiction was a result of his fame and wealth. If he had never made it out of the projects, would these same folks care?

Such a double standard left Michael eternally disillusioned that such compassion was never extended to his neighbors growing up. Such a difference in attitudes was not merely threaded along racial lines, but class lines as well.

While Michael may have moved out of East Flatbush, his heart never left.

Michael frequently returned to Vanderveer, eagerly reconnecting with his neighbors who still call the complex home. He would work alongside State Assemblymember Nick Perry to lead clothing, food, and school drives. Michael geared many of his presentations towards the community's youth, hoping to help carve a path for them that was more empathetic than the one he had traveled. Michael’s trademark humility - one of his most oft cited characteristics amongst the many tributes that have poured in after his untimely passing - was on display every time he visited Vanderveer:

“We couldn’t believe that he was just walking around like he wasn’t a Hollywood celebrity,” said Nena Ansari, 66, of Flatbush. “People were just like, ‘Is that him?’ We were shocked to see him walking around without security guards. But he was a regular guy.” (The New York Times)

Michael’s consistent involvement within East Flatbush led him to Edwin Raymond, a police lieutenant and prominent activist in the neighborhood. Raymond gained notoriety when he and 11 other Black and brown officers sued the City in 2015, alleging that the NYPD had pushed them to discriminate against racial minorities. Michael and Raymond formed a compelling team, both working to help the community, one from the inside, the other from the outside. Michael eventually brought Raymond to the Academy Awards. As both men appeared together on the red carpet, Michael refused to take questions unless reporters interviewed Raymond first. Michael was always willing to use his platform to elevate members of the community.

Before his passing, Michael started a production company, Freedome, designed to produce and amplify work of local Black artists while casting everyday community members in small roles throughout the projects. The goal was not only to give an economic lift to Black people throughout Central Brooklyn, but to provide a medium to share stories and art unfiltered. Something that would always belong to the community.

Michael also co-founded “We Build the Block” with Dana Rachlin, an organization dedicated to replacing the over policing of Brooklyn’s Black neighborhoods with community-led public safety models. Michael and other members of “We Build the Block” focused on voter and civic engagement to combat issues of gun violence, under-funded schools, food deserts, and lack of employment opportunities. The organization advocates for divesting money from the NYPD’s budget into social service investments throughout many neighborhoods that are traditionally overpoliced.

Michael’s advocacy led him to publicly challenge Eric Adams about narratives Adams had put forth regarding rising crime in the City. During a forum in Brownsville hosted by “Crew Counts”, Michael pointed to how Adams’ willingness to put more cops in the subway and on the streets resembled “traditional ways of dealing with us and our youth and in the community.”

While he did not often engage directly with electoral politics, Michael endorsed leftist Chi Ossé for City Council in the 36th District, which includes most of Bedford-Stuyvesant and North Crown Heights. His endorsement came early - in December 2020 for a June 2021 primary - before almost anyone, even hard core insiders, began paying close attention to such races. Ossé was just 23 years old at the time, evidence that Michael was always eager to elevate the next generation.

Ossé, a Black Lives Matter organizer who identifies as queer, was firmly positioned outside the City’s entrenched political establishment, which was a source of great inspiration to Michael: “When I think about what Brooklyn means to me and what I want it to be for the young Kings and Queens living in the neighborhoods most impacted by gun violence, gentrification and over-policing I know that Chi will deliver through policy, moral courage and relentless advocacy.”

Before the City’s progressive organizations and politicians caught onto Ossé, Michael was there to offer him support and an unflinching ally.

Born to a Haitian father and a half-Black, half-Chinese mother, Ossé says his family, and his upbringing in Crown Heights, is “Brooklyn in itself”. Such a statement by Ossé echoes the sentiments expressed by Michael when reflecting on his mixed childhood in Flatbush.

Many of the same violence interrupter programs championed by “We Build the Block” and “Crew Counts” were central to Ossé’s City Council campaign, helping to seize power from the inside for their movement. Next year, Ossé will be able to vote on the new City budget, as he and his colleagues will have the opportunity to invest more resources in overpoliced communities. Michael, who has previously testified before the City Council about the benefits of re-allocating NYPD funds into social services, was undoubtedly proud of Ossé, who will be a part of the most progressive incoming class of councilmembers in City history.

Such elected officials have the responsibility to carry out Michael’s vision of viewing all of New York’s many communities and neighborhoods with the humanity they deserve.

One of the most enduring and endearing videos of Michael is a seven minute clip from celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain’s show, No Reservations. The video is part of the show’s series finale, which centers on Bourdain’s travels across the world enjoying native cuisine with the area's locals. The final episode is set in Brooklyn, and Michael is the first guest. Together, both men walk around the Vanderveer Estates before stopping for Caribbean food at “Gloria’s” Restaurant in Crown Heights.

As they walk through Vanderveer, Bourdain, who grew up in neighboring Manhattan, bemoans the fact that he never “really got to know Brooklyn”. Specifically, Bourdain was referring to the Brooklyn that Michael knew so intimately and had influenced him throughout his life. Such a world, while mere miles away from Bourdain, had eluded him up until that moment. Bourdain, despite traveling all across the globe, said such ignorance was “pathetic.” He was never one to mince words.

However, Bourdain’s reflection is critical because it allows for growth amidst curiosity. While he does not excuse himself, he lays the groundwork for future exploration. In spite of his lack of knowledge, Bourdain exhibited the empathetic engagement that Michael believed is so integral to the human condition.

Throughout their time together, Michael is eager to share his love for Brooklyn with Bourdain, showcasing a deep appreciation for the Italians, Russians, Hasids, and West Indians who make up the beautiful mosaic that is his home borough.

But Michael’s love for his neighbors at Vanderveer and throughout East Flatbush shines through brightest. As they walk throughout the neighborhood, Michael is consistently pulled aside and greeted with tremendous enthusiasm and warmth, further evidence of his impact on everyday working people. Not only did Michael seem comfortable and at home, but he appeared truly happy, as his large smile radiated through the camera’s lens. Bourdain was left grinning, “Michael has not forgotten the people he grew up with, and they sure as f*** haven’t forgotten about him”.

What makes this scene particularly heartbreaking is that both Michael, who passed away earlier this month, and Anthony Bourdain, who lost his life to suicide 2018, are no longer with us.

Such tragic deaths underscore the painful reality that suffering is present all around us, in one form or another. Michael recognized such anguish, and committed his generational talents to provide an honest, human portrayal of that pain, at great personal cost.

Michael’s struggles with substance dependency and anxiety were evidence of his finite humanity, which given the context of his accomplishments, makes his life all the more exceptional.

His altruism made him a modern day superhero who was able to transcend the bounds of society’s narrow perceptions and alter them to be more humane.

While Michael’s legacy is secured by the lives he touched directly, it is immortalized by the folks he impacted indirectly.

Michael worked to shift narratives - about Black men, gays, and the stigma of substance abuse - that were never convenient nor easy. He confronted these challenges with tremendous courage and bravery. Michael showed empathy to everyone he encountered, and it was evidenced throughout his work and the way he lived his life.

Michael will be remembered by the millions he inspired with his unique gifts.

But more importantly, he will be remembered for the visibility he helped give to millions more.

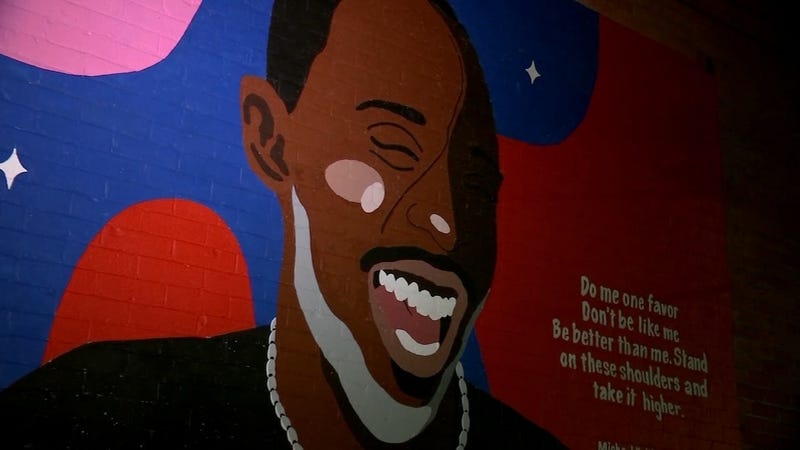

Rest in Power Michael Kenneth Williams.

If you liked this piece, please consider sharing with your friends, family, and colleagues (especially on Twitter - that’s most helpful) as every little bit makes a big difference :)

If you enjoy my content and find yourself coming back, please consider a paid subscription ($5/month) - The more folks who subscribe, the more time I can spend writing

Connect with me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com