"He is fresh, everyone else is tired"

How the 1969 New York City mayoral race shaped the modern Democratic Party

New York City is headed in the wrong direction.

A reform candidate emerges, untethered to the city’s political machines, in the mold of Fiorello La Guardia. Handsome and dynamic, he excites tens of thousands of volunteers and is aided by a left-leaning third party. Raised on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, his ethnic background and upper class upbringing are considered liabilities by the political class. On the campaign trail, he is accused of sympathizing with “communists.” Young voters, disillusioned by war abroad, flock to the polls. Trailing until the final days, the candidate consistently walks the streets of working-class neighborhoods, shaking hands of passersby. In victory, the press credits a relentless work ethic and appetite for new blood: “He is fresh while everyone else is tired.”

At a moment of vacuum in his Party, the progressive Mayor-elect is hailed as a national model; an avatar for what is possible.

I’m not talking about Zohran Mamdani. I’m talking about John Lindsay.

Sixty years ago, the latter entered City Hall with momentum, but lacked a wide mandate for his agenda. Young, ambitious, college-educated bureaucrats — motivated by his message of reform — flocked to his administration, but struggled relating to union leaders and power brokers, still a staple of the city’s political tapestry. As middle-class families fled the outer boroughs in droves, New York City’s tax base thinned precipitously, forcing the mayor to borrow against the city’s assets, foreshadowing the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. In the pursuit of noble reforms, like adding civilian members to the city’s police reform board, increasing community control over public schools, or building scatter-site housing in middle-class neighborhoods, the progressive mayor faced intense backlash from the white working-class.

In 1965, the Lindsay coalition — the business elite, affluent Manhattan Republicans, lower-middle-class Catholic homeowners, liberal Manhattan reformers, middle-class Jews, and a small but significant number of Blacks and Puerto Ricans — resembled the northeastern liberal wing of the Republican Party. However, the late sixties, a period of unprecedented racial and cultural strife in American history, dramatically realigned the Democratic and Republican parties (to an extent still felt today), with John V. Lindsay and New York City at the epicenter.

Once hailed as a future Presidential candidate, in the mold of New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Lindsay saw the Republican Party embrace the more conservative Richard Nixon, whose “Southern Strategy” proved as popular among the white-working class of the urban North as it did in suburban Dixie. Running for re-election in 1969, Lindsay lost the Republican nomination to John Marchi, an unknown and uninspiring state legislator from Staten Island; a triumph not rooted in oratory skill or campaign prowess, but solely because Marchi was the non-Lindsay candidate. A similar wave of backlash swept the Democratic Primary, as Comptroller Mario Procaccino, a conservative Italian from the East Bronx, felled both the Democratic establishment, lined up behind former three-term mayor Robert F. Wagner, and the Party’s liberal institutions, who supported Bronx Borough President Herman Badillo.

Indeed, liberalism was in retreat.

TIME magazine’s 1969 Man and Woman of the Year, ‘The Middle Americans,’ represented a silent majority who resented attacks (welfare, pornography, drugs, crime, protest culture, militancy) on their middle-class values, and increasingly felt ignored by coastal elites. New York City’s “Middle Americans” were German, Irish, Italian, Polish, Greek, and Jewish immigrants who were either civil servants (teachers, fireman, policeman), union members (welders, electricians, carpenters), or members of the petit bourgeoisie (clerks, accountants, small businessmen).

(Vincent Cannato, The Ungovernable City)

Rejected by the Republicans and divorced from the Democrats, Lindsay ran for re-election with the support of the Liberal Party; a symbolic last stand for progressivism in New York City.

“The Revolt of the White Lower Middle Class,” detailed by Pete Hamill, embodied the campaign of Mario Procaccino, derided by the cosmopolitan class as the “frenetic voice of a reactionary Democratic bloc” (Hamill’s essay became a favorite of President Richard Nixon). Undoubtedly, the liberal mayor lacked an understanding of the outer borough worldview. Were crime to spike and quality of life to deteriorate, across neighborhoods on the precipice of the ever-expanding “ghetto,” the sequestered elite of Manhattan (Lindsay’s social circle) would remain insulated behind their doormen; whereas their white ethnic counterparts, the small homeowner class, would not. However, there was a darker side to Procaccino’s appeal, one rooted in racial backlash that went far beyond cultural grievance (Procaccino coining the term “Limousine Liberal”). Lindsay, whose record on Civil Rights was excellent, was sensitive to the plight of poor Black and Puerto Ricans, the city’s most marginalized residents, condemned to a life of poverty and welfare with little hope of escape.

To the “White Lower Middle Class” and the “Middle Americans” at the heart of Mario Procaccino’s coalition, John Lindsay only cared about them.

“Mario says, ‘A safe city and a clean city,’ and he says this not with Protestant coolness, but with the Ellis Island heartbeat which had so much to do with the making of New York. Suddenly it is not good to be so tall and handsome.

‘Send Lindsay to a dance,’ the cabdrivers yell.”

(Jimmy Breslin, New York Magazine)

Procaccino, a proficient retail-campaigner who resonated with blue-collar whites, spoke the language of the alienated and powerless middle-class; Lindsay, tall and handsome, enjoyed almost uniform support from elite institutions: editorial boards, unions, celebrities. Those institutions, trusted and respected, portrayed Procaccino as a caricature of himself (tinged with anti-Italian prejudice) — not that he made it particularly difficult. The Bronx Democrat remarked that his running mate, Francis X. Smith, “grows on you like cancer.” Repeatedly embellishing his resume, Procaccino claimed he was the President of Verrazano College (it did not exist). Contrasted to Lindsay by the media at every turn, an insecurity swiftly consumed Procaccino, to the point where he carried around a copy of his law school transcript to show reporters. Addressing a Black audience, Procaccino’s plea – “my heart is as Black as yours‘’ — encapsulated his ignorance. Golda Meir, the Prime Minister of Israel, attended a twelve-hundred person event hosted by the mayor on the eve of the General Election, signaling to attuned Jewish voters that “the Israeli best interest was to keep Lindsay.” Procaccino did not receive a single newspaper endorsement (The New York Times not only endorsed Lindsay once, but twice), while the unions lined up behind the mayor who negotiated their contracts. All the “beautiful people” voted for John Lindsay; only the “stoop sitters” voted for Mario Procaccino.

In defeat, Procaccino claimed the election was stolen. Lindsay, who earned only a plurality of the vote, called his triumph, “a commitment by the City as a whole to progressive government.”

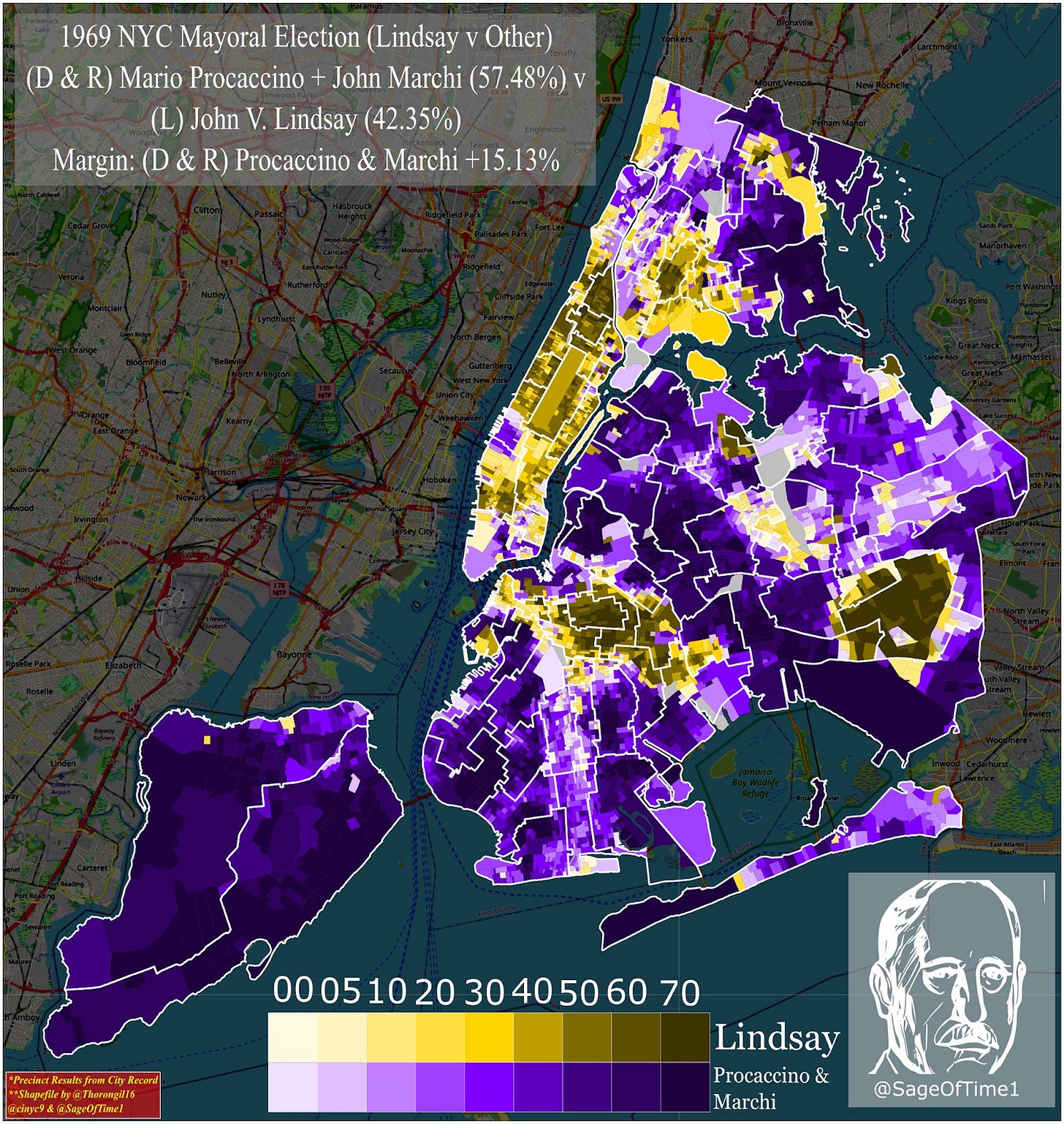

If a picture is worth one-thousand words, then the map of New York City in 1969 tells a story of five boroughs amidst profound demographic and cultural upheaval. From a distance, one can glean the “beautiful people” of Manhattan, who bequeathed near unanimous support to one of their own, John Lindsay; the ancestral Republican outposts of Maspeth and Breezy Point, Bay Ridge and Staten Island, whose votes were delivered to John Marchi; and the sea of outer borough blue, a tide of white ethnic reaction and law-and-order rhetoric on behalf of Mario Procaccino. The migration of Black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers can be seen, block-by-block, in the pro-Lindsay precincts of Central Brooklyn and the South Bronx. The handful of remaining Italians, many of whom supported socialists Vito Marcantonio (and Fiorello La Guardia) in their respective campaigns three decades prior, can be seen as lonely islands of Procaccino holdouts in an ocean of Lindsay support across Harlem.

In Manhattan, John Lindsay took over two-thirds of the vote, finishing with 85% of the Black vote, 65% of the Puerto Rican vote, and 45% of the Jewish vote. Young voters, from students to reform-minded professionals, increasingly left-leaning and catalyzed by the Vietnam War, spearheaded Lindsay’s volunteer operation — becoming a formidable voting bloc in their own right. The unsophisticated Procaccino campaign, little more than a “one note denunciation of crime,” ran-up-the-score with New York City’s “Middle Americans,” but was crushed by liberal institutions and the Black and Hispanic working-poor. Marchi, running a distant third, split the anti-Lindsay coalition, allowing the incumbent to win with only forty-one percent of the vote.

John Lindsay’s arc foreshadowed the Party realignment half-a-century later; with his 1969 coalition — Blacks, cosmopolitans, the college-educated, Hispanics, and ideologically motivated youths — serving as a precursor to the modern Democratic Party. In creating a new, multi-racial coalition of the top and the bottom, Lindsay had lost the middle-class. In the late sixties, as progressives were wiped out of elected office across the country, Lindsay’s survival was notable, but it also represented the high watermark of his second term. As Richard Nixon shifted the Republican Party to the right, the left-liberal mayor registered as a Democrat, his cultural and social liberalism reviled by the emerging Republican base.

The coalitional differences between Procaccino and Marchi, both Italian, are instructional as well. Marchi, the patrician northern Italian (the vast majority of New York’s Italians trace their roots to Southern Italy), drew on a more well-heeled, suburban base of sequestered conservatives. “Many Italians thought Marchi (pronounced: Markey) was Irish, not Italian… In some ways, Marchi was as foreign to most ethnic New Yorkers as Lindsay,“ wrote Vincent Cannato in The Ungovernable City. Whereas Procaccino’s voters, more blue-collar and in closer proximity to racial encroachment, backed the candidate whose rhetoric, inflammatory and apocalyptic, matched their own emotion. The precincts in the heavily Italian enclave of Belmont, well-depicted in A Bronx Tale, gave Procaccino almost 80% of the vote, their last line of defense as the blight of the South Bronx inched northward. In Canarsie, a middle-class Brooklyn neighborhood surrounded by water on three sides, strong support for Procaccino (and lack thereof for Lindsay) informed the thesis of Jonathan Reider’s sociological book, The Italians and Jews Against Liberalism. For many of the white families who could not flee the city, a fortress mentality kicked in, their neighborhood under siege from “limousine liberalism,” forced busing, and cultural change.

From his office on Avenue Z in Southern Brooklyn, Fred Trump tapped into this zeitgeist. In 1969, Trump was in the process of handing off the family real estate business to his eldest son, Donald. Fred’s staunch backing of the outer borough Democratic machines (which all stuck by the party nominee), is small evidence of a Trump–Procaccino connection; but the symmetry is far more subtle. Not long after the election, the federal government charged the Trump Management Corporation with discriminating against African Americans seeking apartments in the thirty-nine buildings the firm operated. If the son craved the acceptance of the “beautiful people,” and wanted, desperately, to become one of them; the father, who lived in Jamaica Estates and worked in Sheepshead Bay, not only built housing for the “stoop sitting voters,” but shared their worldview. When the former ran for President in 2016, he faced silk-stocking opponents (John Kasich) reminiscent of Lindsay and those whose lack of charisma (Ted Cruz) was matched only by Marchi. Returning home to New York, Fred’s son swept the modern-day Procaccinos, blasting apart his Republican rivals in Broad Channel, Tottenville, and Brighton Beach. After watching New York City’s “Middle Americans” forsake liberalism decades ago, Trump nationalized Procaccino’s backlash campaign perfectly, shattering the so-called blue wall in the white-working class Upper Midwest on his way to the White House.

When Donald Trump told four non-white congresswomen (Ayanna Presley, Ilhan Omar, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib) to “go back to where you come from,” many were aghast; but the President was channeling his outer borough upbringing.

You could hear the echoes of Mario Procaccino.

John Lindsay acts as both a cautionary and inspirational tale for Zohran Mamdani on the nuances and limitations of coalition building atop the nation’s largest city.

Sixty years later, we have a very different New York City. The white ethnic homeowner class, save for pockets of sequestered waterfront enclaves, have since absconded from the five boroughs. The richest and poorest Democrats voted for Andrew Cuomo, while the new working and middle-classes — renter-majority, youthful, college-educated, ethnically and racial diverse — formed the bedrock of Mamdani’s movement, the “Coalition of the In-Between.” New York’s civic and cultural institutions (newspapers, unions, machines) ensured John Lindsay won re-election; sixty years later, they lined up to stop Zohran Mamdani, and failed miserably.

For John Lindsay, supported by the wealthiest and lowest income New Yorkers, the working and middle-classes remained not only an Achilles Heel, but a foreign constituency. The journalist Jimmy Breslin, who frequently praised the progressive mayor, nonetheless questioned whether Lindsay was too tall to be Mayor: “Take Lindsay off the front pages and put him on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. Put him there with the schools closed and the garbage not picked up and the robberies and assaults way up… Do this, and you do not have a towering figure anymore. You have a bony Protestant from Yale and Wall Street whose height makes him a conspicuous target for the stumpy little people who yell up at him.”

Despite sharing Lindsay’s upbringing on the West Side, Mamdani did not cut his teeth in the “Silk Stocking” neighborhoods of Manhattan, but across the outer boroughs: canvassing in Glen Oaks, managing campaigns in Bay Ridge, before being elected to the State Assembly in Astoria. After a flurry of suicides in the Sikh community, Mamdani went on a fifteen day hunger strike alongside Taxi drivers to win debt forgiveness for their medallions. His mayoral campaign, from inception, was focused on bringing new voters into the political process: rent stabilized tenants, Muslims, and South Asians. While Lindsay was comfortable walking the firebombed streets of the South Bronx or the slums of Brownsville, the liberal mayor struggled to grasp the outer borough mind, or relate to the worldview of Woodhaven Boulevard, New Utrecht Avenue, or Pelham Parkway. Mamdani, aided by the changing racial complexion of New York City, has built goodwill across these communities; whose class character (and underlying values) have nonetheless remained constant.

In recent days, Andrew Cuomo has resorted to calling the Democratic nominee “shorter Bill de Blasio,” a Trump-esque dig at the six foot Mamdani. However, what the marginally taller Cuomo (ironically) fails to comprehend, is that his own “height” remains the reason why the former Governor is hopelessly behind in the polls, one month away from the end of his career. After years of looking down on others, or not seeing them at all, Cuomo grew too old, too tired, and too out-of-touch.

Too tall to be mayor, indeed.

Lindsay never won a majority of the vote in either of his campaigns, underscoring the deep and bitter divides of the era. This November, Mamdani, versus two well-funded and well-known opponents, has the opportunity to do just that: a clear statement of the democratic socialist’s appeal that manifests in even greater political capital.

Once Lindsay was victorious, much of the neighborhood-level organizing, so tantamount to his campaign’s success, ceased — not to be resumed until his re-election several years later. Mamdani, who was endorsed by the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, is closely allied with a multiple mass-member organization — NYC-DSA, the Working Families Party, DRUM Beats — capable of leading an “outside” organizing arm throughout his term. Such a movement, rooted in electoral politics, gives Mamdani soft power that Lindsay sorely lacked, particularly in Albany; the liberal mayor was routinely steamrolled by Robert Moses (immortalized in Robert Caro’s The Power Broker) and infamously ceded city control of the Metropolitan Transit Authority to the Governor.

Nonetheless, during a period of fervent polarization, Lindsay held the social fabric of the city together. After the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Lindsay walked the streets of Harlem, and New York City avoided the rioting that befell Los Angeles, Detroit, and Newark. On the defining issues of the time, Lindsay remained a staunch critic of the Vietnam War and made Civil Rights a cornerstone of his administration; Mamdani, who has vowed to arrest Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, has helped shift the Democratic Party zeitgeist with respect to the War in Gaza. Through these principled stances, Lindsay maintained his core coalition of younger voters and liberal Jews, similar to that of Mamdani. Most importantly, Lindsay methodically built up his support in the city’s Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, despite the Democratic machine’s institutional advantages. When Lindsay ran for re-election, he prevailed because of overwhelming support from African Americans and Puerto Ricans, the lowest-income New Yorkers. Mamdani, now the Democratic nominee, has the opportunity to do the same in the coming months and years, given people of color are most harmed by the cost-of-living crisis.

However, when his second term concluded, Lindsay was forced into political retirement. Abe Beame, the pride of the Democratic machine whom Lindsay defeated in 1965, succeeded him as New York City fell into fiscal catastrophe. One of Lindsay’s most vocal critics, Ed Koch, went on to serve three terms as Mayor, remaking the five boroughs in his image. Lindsay, who shepherded New York City through one of the most tumultuous periods in U.S. history, watched his political opponents diminish his legacy, reducing the former mayor to “an exile in his own city.” To his enduring credit, Lindsay gave visibility to the plight of the most marginalized New Yorkers at a time when they lacked political or institutional power. An enthusiastic forty-percent of New Yorkers had supported Lindsay twice, but under the stress of the era, the liberal mayor failed to win over those in the middle: the city’s working people.

The backlash to Zohran Mamdani, already bubbling, is far more astroturfed, concentrated in C-suites and editorial boardrooms; whereas John Lindsay enjoyed almost universal support from elites, he failed to win over a majority of the city to his vision of progressive governance. The Mamdani coalition, rooted in the middle-class, centered on affordability, represents a path forward for the Democratic Party, which has consistently hemorrhaged support from the modern-day “stoop sitters” in service of placating “the beautiful people.” For Mamdani to build on Lindsay’s legacy, he does not need comparable support from oligarchs, but the latter’s resonance and goodwill among the Black and Hispanic working class, on the front lines of our political realignment, and most importantly, the costs of living crisis in the five boroughs.

To transform New York City (and the American left), Zohran Mamdani will not only have to build this new majority, but work tirelessly to maintain it.

Connect With Me:

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelLangeNYC

Email me at Michael.James.Lange@gmail.com

Excellent essay. You were almost kind to Mario Procaccino!

I’d love to see a similar deep dive on the ‘77 race with Koch, Cuomo, Bella Abzug, Percy Sutton, and Herman Badillo .

Or perhaps something comparing the ‘93 face off between Giuliani and Dinkins with the '89 race.

Lindsey’s mayoralty though is also a cautionary lesson for Mamdani… Lindsey made mistakes and was “othered” as the out of touch WASP blue blood in ways that were not always fair.

Mamdani will have a lot of powerful revved enemies gunning for him from day one—most importantly the Trump administration, but also the ultra-wealthy, the NY Post and Fox News, Elon Musk’s social media machine, the AIPAC crowd (and those adjacent to it ), crypto bros, etc.

And I do wonder about his instincts and rhetoric on public safety and education, which are third-rail issues in city politics...the kind of things people really care about. I very much hope (and am guessing he will) that he’ll have talented, idealistic, practical, and innovative managers...that is really key.

The affordability issue is potent, but how much can a mayor do about that?

De Blasio tried and didn’t get too much credit for things like universal pre-k, rent freezes, increasing minimum wage to $15, free legal services for tenants, etc.

I’m reminded of the old Jesse Jackson line, “Vote Your Hopes, Not Your Fears.”

Zohoran Mamdani is the way foreward, every other democratic presidential candidates take notes for 2028. ✊, congressional democratic candidates also take notes for 2026.